Having found there was a street in Chelsea named Camera Place I had to photograph it. It’s a short street and my picture shows around half of it, looking roughly west towards Limerston St. Chelsea used to have a Camera Square, Camera Street and Little Camera Street which have since disappeared, but as they were built in the 1820s they almost certainly have little to do with photography. By 1918 Camera Square had become something of a slum and the area was demolished, rebuilt as Chelsea Park Gardens with up-market housing in suburban garden village fashion, though retaining a rigidly square layout without the typical sinously curving streets.

The view in Camera Place has changed little; some new railings and the small tree is now rather large.

Elm Park Mansions has five large blocks around a courtyard, with one of the blocks (flats 25-54) occuping half the length of the north side of Camera Place, behind and to my right as I took the previous picture. The mansions with 189 mostly one and two bedroom flats were built by the Metropolitan Industrial Dwellings Company on land leased to them by Major Sloane Stanley in 1900. The Freehold for the property was taken over by the leaseholders in 1986 and since then the state of the properties has been improved. Two bed flats have sold in recent years for around £800,000.

Elm Park Road dates from 1875 when Chelsea Park House was demolished and the houses, many designed by George Godwin, were built between then and 1882. The central house in this picture, at 76 Elm Park Road for built for Paul Naftel, (1817-91) a Guernsey born watercolour painter and his wife and family who came to London in 1870. He moved here in around 1884 and the adjoining houses were also homes to landscape artists. Naftel later moved out to Strawberry Hill, Twickenham where he died.

The Grosvenor Canal was began by the Chelsea Waterworks Company who had leased the land from Sir Richard Grosvenor in 1722, and enlarged a creek there to supply drinking water and also to create a tide mill used to pump the water. When their lease expired in 1823, the then Earl of Grosvenor decide to put in a lock and turn the creek into a canal, extending it to a basin where Victoria Station now stands, around half a mile from the Thames. It opened in 1824 carrying coal, wood and stone into the centre of a rapidly growing area of London.

Victoria Station was built over the canal basin, and more of the canal closed in 1899 for a station extension. Westminster City Council bought what was left of it in 1905, then filled in more of it in 1927 for the Ebury Bridge estate.

The canal continued in use by the council taking refuse in barges from Westminster and other local authorities downriver to be dumped until 1995, making this vestigial canal the last in London in commercial use. In 2000 it began to be developed as an expensive waterside development, with the lock being retained but a boom across the entrance from the Thames prevents access for boats despite mooring pontoons inside the development.

The Chelsea Water Works continued to extract water from the Grosvenor Canal until an Act of Parliament prevented extraction of water from the Thames in London in 1852 and they moved up-river to Surbiton. Sewage was increasingly becoming a problem as London grew and the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858 prompted Parliament into action, passing a bill in 18 days to construct a new sewerage system for London.

The solution by Joseph William Bazalgette was a system of sewers that delivered the sewage around 8 miles downriver to Beckton on the north bank and Crossness on the south, through main high level middle and low level sewers through North London and main and high level sewers in South London. The plans included stone embankments beside the river – the Victoria, Chelsea and Albert embankments which he designed.

Bazalgette didn’t do everything himself, but he kept a very close eye on every aspect of his great project, and some of the specifications he laid down – such as the use of Portland Cement – have kept the system running despite increasing demands since it was completed in 1875. Now it is being augmented by the new ‘Super Sewer’ running underneath the river, the Thames Tideway.

As well as engineering considerations, Bazalgette was also a stickler for the aesthetics and there are some fine examples of Victorian design in his works. The Pumping Station which housed the powerful steam engines needed to send the sewage on its way, as well as its chimney (in a picture above) and the Superintendents House here are all Grade II listed.

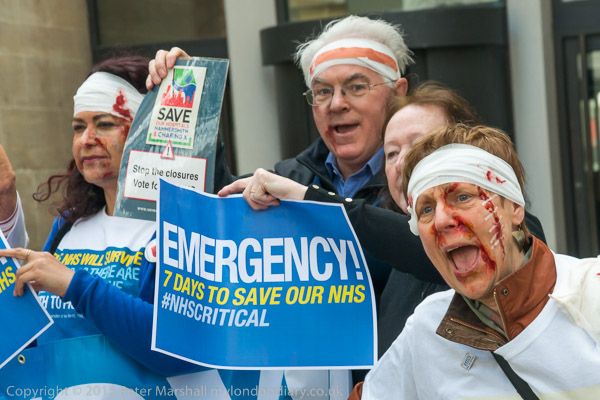

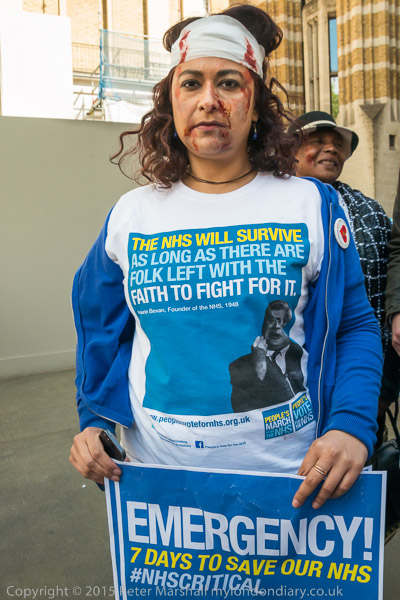

All photographs on this and my other sites, unless otherwise stated, are taken by and copyright of Peter Marshall, and are available for reproduction or can be bought as prints.