Recently I’ve gone back to scanning quite a lot of my older negatives and, as I’ve mentioned in previous posts, have been using the Epson V750, simply for its speed, rather than the Minolta Dimage Scan MultiPro.

Although the scans have been good enough for my needs at the time, I’ve always felt that for the optimum quality I would need to go to the dedicated film scanner. But I wanted to find out exactly what the difference was and so to decide when to use a film scanner.

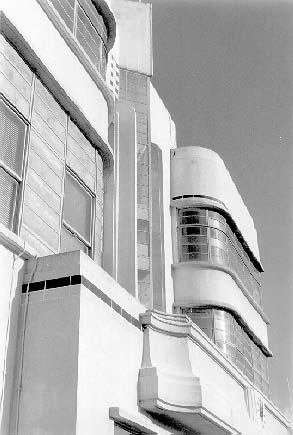

Brixton, 1980, taken on a Minox EL 35mm camera

I chose this negative simply because it was one I wanted to print, having spent some time searching for it in my archive.

Minolta are no longer with us, and the MultiPro scanner which was the best of its type is no longer made. The scans made with it are of similar quality to the best scanners still available, including some considerably more expensive models.

All images in this post are unretouched scans, though I’ve adjusted contrast a little to give a better match than in the actual scans – though they are still not quite the same.

Minolta Dimage Scan MultiPro

I put the negative into the universal carrier with a specially made full frame 35mm mask that ensures film flatness and set the software to 4x sampling to get every last ounce out of the negative, scanning at 4800dpi.

Then I went and had a cup of tea while the scanner got on with the job – which I think took around 15 minutes – and produced a 58Mb 16 bit grayscale TIFF file.

a 600×400 section from the 6829×4541 scan, displayed at 2/3 size on this blog

Viewed at 1:1 on the screen (the full 6829 pixels would actually produce a picture 73 inches wide if my screen was large enough – although nominal screen resolution is 72 dpi, actual screens invariably differ from this) the image is pin sharp and shows a fine granular pattern which I think is the actual film grain. The grain is as sharp at the edges as it is at the corners, and it is a pretty impressive performance.

An area where the white threads are more visible

Unfortunately it also shows something else, with large areas of the image being marred by fine white thread-like lines. I’ve tried to remove these by various Photoshop filters, but doing so also blurs some of the fine detail (and the grain.) Retouching using clone and healing brush tools also loses a little of the detail and is extremely difficult and tedious – and would involve several hours of work.

Minolta Dimage Scan MultiPro and Scanhancer

I’d made this first scan without the http://www.scanhancer.com/ Scanhancer which radically improves its performance in place, so the next job was obviously to try it with this. So it was time for a coffee as I let it do its work.

The Scanhancer is a simple plastic diffuser that sits on top of the negative, and it was developed by Erik de Goederen and others on the MultiPro user group. Minolta (and some other scanner manufacturers) liked the idea so much that they incorporated the idea into later scanners.

Although most diffusing materials make a difference, the choice of the right material is crucial. But as the site says, it allows the Multipro to rival “drum scan quality by mimicking the effect of wet mounting.”

a 600×400 section from the 6821×4568 scan MultiPro + Scanhancer

And, somewhat to my surprise it solved the problem – those white threads simply disappeared. It also slightly reduced the rather aggresive grain in the image.

Epson V750

Using the V750 with the film in the standard film holder did the scan at the same nominal resolution, 4800 in around 2 minutes – about a tenth of the time. It isn’t as sharp when viewed 1:1, and the grain is more a texture than the discrete pattern of the MultiPro scan, making some surfaces noticeably smoother. In fact it makes me begin to wonder if the ‘grain’ in the MultiPro scan is actually some kind of scanner artefact. The negative clearly isn’t flat, but the scan doesn’t show any really noticeable loss on this account. Because of the design of the holder it isn’t quite possible to scan quite the entire negative (more of a camera fault in the very slight skew of the frame on the film) but the difference is very small.

a 600×400 section from the 6792×4419 scan, Epson V750

But although it clearly is slightly less sharp, there is more or less the same amount of detail on the scan (though differences in contrast and brightness may mean this isn’t clear) and, as with the Scanhancer, those little white threads have simply disappeared. Flatbed scanners have more diffuse light sources than most film scanners.

a 600×400 section from the 6792×4419 scan, Epson V750, after sharpening

A little sharpening using a tool such as the FocalBlade plugin can bring the sharpness at the maximum print size (33.3% on Photoshop gives a display on my monitor corresponding to a print at around 280 dpi, and an image size around 24×16 inches) to a similar level as the Multipro scans. At this size the main difference is actually the grain apparent on the Multipro scan, and I can get a better visual match in Photoshop by adding a little noise to the V750 scan should I want to!

It did occur to me to wonder if I could get a sharper scan direct from the V750. I tried the unsharp masking in the scanning software but decided the sharpening in Photoshop was better.

I also tried using the V750 with the same Vuescan Pro software that I use with the MultiPro (one of Vuescan’s big advantages is that it will work with almost any scanner ever made.) The scans produced were pretty similar with those from the Epson software – and using the 4x sampling didn’t seem to make any difference, except to speed. So as the Epson software did the job faster I’ll stick with that in future for this scanner.

The main problem with flatbed scanners such as the V750 is the lack of focussing. All you do is adjust the feet on the negative carrier to move it up and down slightly. I’d previously tested the carrier to arrive at the current setting of the feet, so felt fairly sure altering them wouldn’t help.

Although I couldn’t see much effect on sharpness, the curving of the film in the negative carrier did actually result in a very slight distortion of the image around the edges. It was only noticeable by comparison with the Minolta scans, but I still don’t like it.

I’m told that wet mounting does improve the performance of the scanner significantly, but have yet to try it. But there have been some reports that the Scanhancer can work a little of its magic with flat beds too, and it is a lot easier than wet mounting, so I thought it was worth a try. There was perhaps a very slight improvement in sharpness, but it was hardly significant.

Conclusions

Although there is a small difference in sharpness – particularly of the grain – when viewed at 1:1, both scanners give files entirely usable results at normal print sizes – up to perhaps 24×16 inches.

Some viewers actually prefer the look of the Epson V750 scans because they reduce the effect of film grain, giving a slightly smoother look to some surfaces.

If you are intending to print to very large sizes – perhaps A0 or larger – then the slightly increased sharpness of the MultiPro would almost certainly be preferable. The Scanhancer is essential for removing some imperfections when scanning old negatives like these, and slightly reduces the aggressive grain.

The question that really persuaded me to carry out these tests was whether the V750 scans would pass the quality control tests imposed by Alamy. Frankly I can’t guess at the answer, but as usable files for almost any purpose they should do.