I was interested to read a post on Facebook by Pete James, Curator of Photographic Collections at the Library of Birmingham (UK) about a new biography of Mike Disfarmer, self-published on Amazon as an e-book by Kim O. Davis last week. You can read a little of the book ‘Disfarmer: Man Behind the Camera’ free on line and of course purchase the whole. The result of two years of research, the book would appear to tell us all that will ever be known about the photographer, who died in 1959, now 55 years ago.

From the index on-line we can see that most of the details that might be of interest about his photography are still simply suppositions, though it would appear that Davis has a great deal of new material on his background and early life. There appears to be little if any new information not already available in the sample material,and at least one error leapt out at me, when Davis writes that before the early 2000s it had been “erroneously believed that no actual Disfarmer prints had survived.” Of course, as Julia Scully, whose 1976 book with Peter Miller (and show at the ICP) brought his work to the notice of the wider photographic world, had written: “Many of these originals are still to be found in the photo albums of Heber Springs families“.

But it was only when New York photo collector Michael Mattis set in motion an organised search to buy up these images around Heber Springs in 2004 that around 3000 vintage prints were acquired from these families. You can see much of Disfarmer’s work and also read about him in the Disfarmer Project web site, which also has a short biography by Richard B. Woodward from the 2005 book Disfarmer: The Vintage Prints.

Although Disfarmer’s life is intriguing, I wonder if knowing more about it really tells us more about his life’s work. Perhaps it is more worthwhile to examine his photographs rather than his peculiarity and peccadilloes.

Roughly nine months before Mattis set up that project, I’d tidied up my notes about Disfarmer from an earlier talk, and added a few comments to them and published them on line as one of my regular weekly series of features on photography and photographers. I can’t now recall why I did so at this time, but probably Disfarmer was in some way in the air. It was a piece of work that elicited more interest than most – including an appreciative e-mail from Julia Scully making a minor correction to what I had written. At the time I wrote there was far less material available about the photographer and far fewer pictures on line. I’ve corrected a few typos, but otherwise here is what I published in May 2003.

============================================

Mike Disfarmer – American Portraits

Disfarmer’s Origins

Birth and Family

Mike Meyer‘s parents came to America from Germany some time before his birth in Illinois in 1884. When he was young the family moved to Stuttgart, Arkansas, now apparently widely known the “Duck and Rice Capital of the World” and home of the World’s Championship Duck Calling Contest. Stuttgart had been settled by German Lutheran farmers, many of whose descendants still farm the same lands.

He was the sixth born of seven children, and the only unusual thing his relatives remember about him as a child was his musical ability. He had a fine ear for a tune and played several instruments including violin, piano and accordion.

Work

Meyer’s father died when he was around 14, around the time he went out to work. He continued to live with his mother and worked as a night watchman at the rice mill in Stuttgart.

At some time fairly early in his working life he became interested in photography and bought himself a camera; and taught himself how to use it. We can only speculate what books or magazines on the subject he read – at this date or later.

Move to Heber Springs

In 1914, his mother decided to move to Heber Springs because of its better climate, and he moved with her. There, he set up his first photography studio, in the open at the back of the house. Before long he was in partnership as a photographer with a studio in the main street.

The Cyclone

The climate was not kind to his mother, as a cyclone (probably the great cyclone of Monday, June 5, 1916, which killed 22 Cleburne County residents, although there was another disastrous one on Thanksgiving Day, 25 November 1927) destroyed the house. Meyer was apparently mentally scarred by its effects, although he soon recovered from any minor physical injuries – none of the Meyers are listed among the 1916 casualties. His mother moved out to live with one of her sisters, and he also left home.

Penrose & Meyer

The Penrose & Meyer studio was on Main Street, in the same building as the Jackson Theatre, one of the earliest movie theatres in Heber Springs, built in 1912. Penrose was perhaps an existing local photographer, but nothing seems to be known about him. Unfortunately the block was destroyed in a fire in 1921, and he had to find new premises.

New Studio

The new studio Meyer built was some 20×30 ft, slightly above the typical size for daylight studios and its design was described as modern, perhaps because of its plain backgrounds. It had a wall with large windows fitted with blinds that could be used to control the north light Meyer favoured for his pictures. In the 1930’s it became a popular place to go and have your picture taken in Heber Springs, one of the few attractions in this small town.

Birth Delusions

At some point after the cyclone, Meyer became convinced that the family in which he had grown up was not his own. He got the idea that there had been a cyclone at the time of his birth, and that during this he had been confused with the Meyer child. His own parents had been of a much higher class, more cultured and intelligent than the Meyers.

Such delusions are perhaps not as uncommon as we might think, and pass idly through the minds of many, perhaps especially those whose behaviour suggests mild autism, as some of the descriptions of Meyer might suggest. Meyer took his thoughts further to the point of an obsession, more or less breaking off relations with his real family and changing his name.

Disfarmer

The German name Meyer comes from the Middle High German meier (or meiger) which means superior or higher, and became used for more more important farmers. In modern German, Meier means ‘dairy farmer’. (The name can also be spelt Mayer or Meier, and is found from a different root in Jewish families – the Hebrew ‘meir’ meaning enlightened.)

Meyer was convinced he was not truly of German stock and was not from a family of farmers. He invented a new name for himself to express this: Disfarmer.

Small Town Studio

Heber Springs

Heber Springs was a small town of around 2000 people, although many of the studio clients will have been from the surrounding country of Cleburne County, Arkansas. The town is at the foot hills of the Ozark Mountains, and virtually the only industries at the time were farming and logging. Cotton was the main crop in the southern part of the county, and throughout the area many farmers were living at subsistence level.

Disfarmer’s Assistant

Julia Scully (see below) was able to interview Mike Disfarmer’s assistant, Bessie Utley, who worked for him when the studio was popular in the 1930s and 40s. She not only developed his plates but also often cooked for him.

Utley found him to be a fine man of superior intelligence, with a firm conviction that “he was the only one who could make pictures.” His conviction that he was superior to other people made it hard for them to understand him, and “made the people think he was nutty.”

Studio Sessions

Despite his oddities – or perhaps they increased the attraction – a trip to the photographer’s became one of the attractions on the trips people made into the town. There they stood in front of the plain dark background in the studio while the photographer carefully adjusted the blinds and got the lighting just how he wanted it.

The Sessions

The town’s funeral director recalled a sitting with Disfarmer, and suggested that it sometimes took him an hour to arrange the lighting. Although he may have worked slowly and thoroughly, it seems unlikely that his clients would have had so long a time to wait. However, it is clear that the photographer took his work very seriously and the results he obtained show this.

Over the years, Disfarmer must have taken many thousands of pictures. As well as the studio work with which we are familiar there were probably pictures taken in peoples homes and elsewhere. Images by Disfarmer must be present in many family albums covering a wider range of his work and it would be of interest to discover if these show the same characteristics as the published work.

Equipment

Disfarmer was said to have used a large home-made studio camera. Like many photographers of the time, he stuck with glass plates rather than changing over to film, at least until around 1945. Joe Albright also suggested that the camera back went through a hole in the back wall of the studio, presumably into a dark area, and that Disfarmer looked at his subjects through a window when setting up the images.

Having the camera back in the darkroom area of the studio would give the advantage of a very clear image on the ground glass screen. If the window through which the photographer viewed his subjects was equipped with a lightproof blind, plates could be loaded or unloaded without a darkslide. However, memories of Disfarmer and the way that he had worked were dim, since over 20 years had passed before the interviews.

A Recluse?

Disfarmer, particularly as he grew older, had had less and less contact with other people apart from taking their photographs, but retained his interest in music. The town barber, John Hendricks, an amateur guitarist, remembered evenings when he and Disfarmer sat in the studio playing together, Disfarmer was still a good fiddle player and enjoyed playing the kind of country music popular in the South.

Perhaps because the war had come to an end, but also possibly because of the photographer’s increasingly offhand and eccentric manner, business dropped off. Disfarmer’s studio remained open until he died at the age of 75 in 1959, but we know nothing of his work in these later years.

Posthumous Fame

Death

Disfarmer became more and more a recluse, avoided by most of the townspeople and he had few visitors, and even fewer customers at the studio. He was there on his own when he died in 1959, and it was two days before his body was discovered.

After Disfarmer’s death, the executors wanted the studio cleared, and Joe Albright, a retired army engineer with an interest in photography, was living in Heber Springs and bought the entire contents of his studio for the token amount of 5 dollars.

Saving the Negatives

Although Albright was disappointed to find no photographic equipment worth saving, he did have the foresight to hang on to the boxes of glass negatives that he found, some 3,000 of them, thinking they might be of some interest to local historians.

The latest of these negatives appears to date from around 1945, possibly suggesting that at this date Disfarmer changed over to using film. Albright kept the negatives in store until around 1974.

Miller and Scully

It was then that photographer Peter Miller and his wife Karen moved from New York to join an Arkansas cooperative corporation ‘The Group, Inc’, and found themselves running the weekly Heber Springs newspaper ‘The Arkansas Sun’. They began featuring old photographs supplied by their readers, and Albright got in touch, offering some of Disfarmer’s work.

It was Miller who recognised that these images were possibly of more than local interest. He made some prints from the negatives and sent a few to Julia Scully at ‘Modern Photography‘ magazine. She too was impressed, and set to work with Miller and Herschel and Elizabeth Coley to find out more about the man and his work

Modern Photography

‘Modern Photography’, edited by Scully since she joined in 1966, was a mass circulation photographic magazine that unusually attempted to take the medium seriously, publishing features by critics including Andy Grundberg as well as a regular column ‘Seeing Pictures’ written by Scully herself.

Many photographers both in the USA and abroad looked to it for a wider view of creative developments, until it was finally swallowed up by its rival ‘Popular Photography’. The texts published by Scully form the basis for all other articles on Disfarmer, including this feature.

Publications

Disfarmer’s work began to be published in magazines and a book appeared in 1976, published by Addison House: ‘Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939-1946‘ with Disfarmer Photographs printed by Peter Miller and text by Julia Scully.

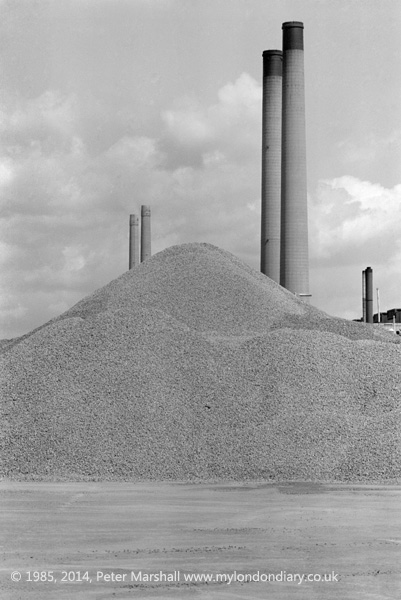

Other publications followed, including a feature by Scully in ‘Aperture‘, certainly one of the highest accolades a photographer can achieve. In issue 78 (Fall 1977) the company was august, including Paul Strand‘s images from his garden at Orgeval, Hilla and Bernd Becher‘s images of preparation plants (“breakers”), colour by Joel Meyorowitz and early pictures by Francis Frith and others from Egypt.

From an unknown and forgotten career in a small town in rural America, Disfarmer had enjoyed a meteoric rise over a couple of years to become regarded by many as a major figure in the photographic pantheon, drawing comparisons to Atget, Arbus and Sander.

Image and Reputation

The Pictures

Disfarmer is said not to have posed his ‘sitters’, and indeed most of them simply stand facing the camera in simple groups. However it is a rare individual who does not look unflinchingly into the eye of the camera, and even rarer one who smiles at at. Whatever he did or did not say to them, Disfarmer clearly imposed a relatively common approach in these matters.

The strength of these images is in part in their simplicity, but their appeal is also very much to do with the character of the people that he photographed. The pictures have a built-in nostalgia, a reference to a time past that for most of us was never present, except in film.

The People

The people here are a past we would perhaps like to think we had, a view of America when the dream was still real, even if those who are shown were not getting much of a share of it.

These are hard-working people, some still in their working clothes, but mainly in their ‘Sunday best’, reserved for going to church or for having your picture taken. Honesty apparently shines through their faces, looking at us from a simpler world where right was right. There is also a fine humanity in them, often most evident in the small imperfections.

Lighting

Disfarmer used soft, overall lighting, probably using reflectors as well as the large north-facing windows which even reduced or eliminated any shadows on the underside of hat brims. Generally the light was slightly directional, coming from the left of camera to produce some slight form shadow which gives the figures their three dimensional quality.

Exposures

His exposures seem to have been quite lengthy – perhaps in seconds – with some faces clearly showing movement blur. The people are clearly concentrating on having their picture taken, staring into the camera with the same kind of intensity that was required for the daguerreotype.

A Collector

I get the feeling that Disfarmer regarded himself more as a scientist than an artist, pinning these people closely against his background and walls almost as if he were making a butterfly collection. But here the subjects respond to his game, some with dour obedience (life was hard and many things just had to be born), some with near terror and others determined to show their individuality through pose or gesture.

For many a trip to the photographers was perhaps similar to a trip to the dentists, something that had to be endured. Young men about to go to war, dragged in by their family to pose with them, and also proud men returning and celebrating.

Although some families will have had their Kodaks, there was still an immense gulf between the kind of small blurred mementos these provided and the carefully composed large format quality of the professional.

Disfarmer and Evans

Although I have no doubt that these are fine portraits of their time, to me the work lacks the complexity of that of Atget and Sander. It is, like its subjects, honest and straightforward.

It has a similar appeal to some of Walker Evans’s work for ‘Fortune’, such as his images of tools, but lacks the complex feelings of those images that he made of share-croppers, articulated both in his photographs and in the text by James Agee that accompanied his work in ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.’

Evans took his pictures as an East coast intellectual coming in to the lives of the share-croppers; while Disfarmer, despite his own certainty that he was an outsider, had known and shared the circumstances of those who entered his studio for all of his life. It is work from a different viewpoint, equally valid but more limited.

Evans – and his colleagues at the FSA – give us a view from the outside, and at times one that was designed to further the aims of the organisation, although Evans himself clearly worked to his own agenda.

In later years, the work of the photographers was more clearly linked to the war effort. Disfarmer had no such pressures, providing a service directly to those he photographed, if one suspects rather on a take it or leave it basis.

Vintage Prints?

I admire Disfarmer’s work, and was pleased to have the opportunity to view some original prints at a recent exhibition. These were prints made from the original negatives, rather than prints made by the photographer himself, and it would be interesting to be able to compare the two.

Those who have edited and published his work appear to have treated it with commendable respect, although it is not possible to know how clearly their selection of his images would reflect what Disfarmer would have considered to be his most important work.

Other Disfarmers?

Disfarmer isn’t a photographer whose work has changed the course of photography, but work that was carried out by someone who remained unknown outside his own small community. It is interesting to speculate on other Disfarmers hidden away in their own small towns around the world, working quietly and diligently cultivating their own gardens.

There have indeed been such claims made for other photographers – including even some from Arkansas – but the evidence that I’ve seen usually fails to support their cases. However, interesting photographers from the past are still being discovered.

It is perhaps less likely in the present that such talent should be overlooked. Had he lived in the present, Disfarmer would probably have been spending a great deal of time on the Internet, creating a web site about his switch at birth and his photographs. Bushels are rarer these days and fewer candles remain hidden.

Louis Clergeau

Of course not all photographers get treated fairly after their death. To judge from John Berger’s review of ‘A Village in France’, Louis Clergeau‘s pictures of life in a small town near Blois in central France from 1902-36, his work has been reduced to an almost meaningless nostalgia.

Rephotography

Photographer Toba Pato Tucker was so impressed when she saw Disfarmer’s work that she went to Heber Springs for two years, photographing some of the same people that he had photographed, as well as their descendants and relatives. The differences her work showed between the 1940s and the later work was the subject of a book by her and Alan Trachtenberg, published by the University of Mexico Press in 1996.

============================================

There are a few things in the piece that we now know more about as a result of further research – and perhaps a few more will arise from the latest publication by Kim O Davis. If I owned a suitable e-reader I might well buy it, but I still prefer to read on paper rather than on screen. But I’m rather more likely to buy a book of Disfarmer’s images.