This article started as part of my lecture notes and was added to at the time of Goldins Whitechapel Gallery show in 2002, and later a version was published on the About Photography web site I was then writing. It has been rewritten in 2007.

For copyright reasons, no images by Goldin are included here. At the end of the article are a number of links to her work on the web, as well as to some other articles about her and several of the other people mentioned here.

Life and Work

The division between photographers lives and their work is sometimes but not always important. That we now know a little more about the life of E J Bellocq, where once all we had were his enigmatic but often stunning images from the brothels of Storyville certainly has not altered the way I appreciate his work, and there remain many photographers who I admire but know little or nothing about.

Some of course have provided us much more. Edward Weston for many years wrote what he felt were his intimate thoughts in his day-books, and although he excised some names and passages with a razor blade before allowing Nancy Newhall to edit them, these published diaries still perhaps still tell us more than we need to know about his personal life, fascinating though it may be at times. What he thought about his work is really of more interest, although his writing sometimes seems too arty and full of pretensions to match the directness of his best and most direct camera work.

Weston’s relationships with women – Magarethe Mather, Tina Modotti and Charis Wilson Weston among others were obviously a vital part of his life and had their impact on his work, which I tried to bring out in my features on him without going into the minutiae of his many relationships. But perhaps these aspects of his titillated his major biographer and others, and distracts them from his work, distorting distort their and thus our appreciation. Landscapes are less sexy than the nude even without the artificial spice of personality journalism, but they may be more profound.

An obsessive record

With Nan Goldin things are different; life and work overlap to the point of identity. As she writes in the introduction to her first book, published in 1986 “The Ballad Of Sexual Dependency is the diary I let people read.” Goldin wanted, or even needed, the camera to become part of her and to “obsessively record every detail” of her life.

Of course the camera can’t oblige. It only offers us glimpses, framed and caught with more or less skill by the person who directs it – and Goldin’s control as a director is remarkable. The glimpses depend on both the technology — lenses, angles of view, depth of field, the film etc — and the plans and decisions of the photographer. These together produce a view of what was there in front of the camera. Photographs are not simply ‘traces’ or some kind of objective replica, but objects that are produced from a particular viewpoint – moral, ethical and judgmental as much as spatial.

Relationships

The taking of a photograph is only one stage of a process. Goldin uses her pictures to tell a story, and in doing so creates her own story. The cover picture of ‘The Ballad Of Sexual Dependency’ (a cropped version of one of the slides from the sequence) shows two people on a bed. Brian, closer to camera, is turned away from it, looking out of the picture to the left. Sitting naked on the edge of the double bed, he smokes a cigarette, detached and apparently deep in thought. A flash to his left, roughly level with his face light it, and also casts the shadow of the brass bed head on the bare wall a few inches from it, as well as catching Nan’s face as she lies awkwardly, head on pillow watching him, anxiously. Her upper body is covered by a black robe from which only her left hand emerges, flat on the sheet, with watch and a gold wedding ring. A golden glow bathes the image, turning everything – Brian’s flesh, the wall – to shades of yellow, orange and brown, the colours of sunset. They are a couple together on a bed, but clearly separate, at different ends, he upright, she horizontal.

It is such a carefully crafted tableaux – and in the un-cropped original, even more clearly so. Looking at this we see how the position of the light draws our attention to the faces of the two people, lighting them and the pillow on which Nan’s head is uncomfortably resting, while casting a shadow behind her and on the lower part of the bed. We also see, staring out at us from the wall a repeat image of Brian, a photograph again with a cigarette, this time dangling from his lip as he gazes intently at camera. The gaze at the camera (and the photographer) in that photograph suggests a quite different relationship from the one we see being acted out in front of us.

As so often in Goldin’s work, this picture combines a remarkable detachment in the creation of the work with a total involvement in the scene she is taking part in. Goldin is always very much a part of her pictures, whether she appears in frame or not. Unlike Diane Arbus, who at times photographed a similar subculture very much as a tourist or an empathetic collector of rare and unusual species, Goldin did not stand and look in; if anyone is a voyeur it is us and not her.

For Goldin, the private – or at least a carefully organised part of it – has become public. This is a picture of a relationship that she had been in for some years and was apparently on the point of breaking up, but we also see that if you wanted to live in Goldin’s life you also had to play her games for the camera.

Death and ecstasy

The book ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency‘, (1986) (Ballad), was dedicated “to the real memory of my sister, Barbara Holly Goldin.” Nan Goldin was the youngest of four children in a very middle class family; born in Washington DC, her family soon moved to Maryland. Goldin at eleven was very close to her eighteen-year-old sister and knew about some of the problems she had in reconciling her sexuality with the attitudes of society, problems that led her to lie down on a railway track in front of a train. A few days after the shock of the suicide, and while she was still desperately mourning the loss of her sister, Goldin was seduced by an older man. Within that week she experienced both great loss and pain and was also “awakened to intense sexual excitement.”(Ballad) These two dramatic events shaped the future of her life and her art.

I find it difficult to imagine the position she was in, with these immense emotional pressures coming at an age when I was still in short trousers and being taught that sex was a Latin numeric prefix. Life was not without its traumas, but mine were less dramatic. Goldin was confronted in those sudden and tragic events with forces that most of us become aware of slowly over a period and evolve mechanisms to deal with or repress, and it is hardly surprising that the issues behind them have dominated her work. I don’t share her lifestyle or some of her attitudes, but I admire the honesty and clarity of her approach.

Goldin ascribes her need to take photographs to the death of her sister. The obsession with recording her friends comes from a realisation that although she remembered the things Barbara has said to her, she had lost “the tangible sense of who she was, what her eyes looked like” (Ballad) and she was determined not to let that happen again. Later when many of her friends were suffering from Aids, she had a feeling she could keep them alive if she photographed them enough. Of course what she could and has kept alive is a memory of them, but her photography has kept her alive also.

A new family

Fearing that she might too literally follow in her sister’s footsteps, Goldin ran away from home and its repressive attitudes at the age of fourteen to be able to live in her own way. She drifted through a series of foster homes, eventually ending up in a flat share with half a dozen other disaffected teenagers. These friends became a new family to her, and among them were two people who were to become her greatest friends, David Armstrong and Suzanne Fletcher.

It was here in the summer of 1972 she first took up still photography, although she had already experimented with shooting movies. Her first photographs – and her cine footage – were pictures of herself and her friends dressed up and with heavy make up, posing dramatically as the movie stars of their dreams. Armstrong was her favourite model – he was just discovering drag – and he also became a photographer.

She describes in ‘The Other Side‘ (1993) how when she first saw drag queens on the street in Boston in 1972 she immediately followed them and shot some Super 8 footage. A few months later, David Armstrong took her to ‘The Other Side‘, a drag club in Boston and introduced her to some. Aged 18, she moved in with a pair and was busy photographing them and their friends.

Fashion and Boston

Goldin decided she wanted to become a fashion photographer and that she would become famous by using the queens as models on the cover of ‘Vogue’. She enrolled in a photography evening class and had her first show in a basement in Cambridge, Mass the following year, with all her models attended the opening in drag. These black and white images are the basis of her series ‘The Boston Years.’

In 1974 Goldin moved out and went full time to study at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, She describes the pictures she took on the course as the worse she had ever done, but it was there that she began to develop the look for which she became noted, switching from black and white to colour, and moving from natural light to an almost exclusive use of flash. Until 1990 she used a 35mm SLR, shooting on transparency film and having this printed using the direct positive ‘Cibachrome’ process (now sold as ‘Ilfochrome Classic’, but still generally known by its older name.)

Cibachrome tends to exaggerate colour, producing highly saturated results which maximizes the apparent sharpness of transparency film. The kind of glow – often yellow or orange – that she gets in some of the pictures comes easily and naturally from this process. In 1990 she switched to working with Leica M6 rangefinder cameras. Some of her more recent work seems to show a more natural lighting effect, possibly through the use of more sophisticated flash equipment with larger reflectors.

Much has been talked of the ‘Boston School’ of photographers, including Goldin and David Armstrong along with Mark Morrisroe (1959-89), Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and Jack Pierson (although Goldin didn’t meet Pierson until 1985 in New York.) They were all of a similar age, moved to New York around 1980, had similar tastes in music and drugs and often photographed each other as well as mutual friends.

New York (and England)

After her art course, Goldin found it difficult to relate to many of her old friends and in particular the drag queens in the same way. She continued to photograph her life and the people in it, without really finding much she could really work with, taking pictures in Boston and travelling around.

In 1978 Goldin and some of her close friends decided to move to New York, where she soon began photographing in the bars and clubs. She also lived in England for a time in 1978-1979, where she photographed punks and mods. The pictures from London have a different feel; the clubs and music were harder, more masculine, more working class, and had little of the artsy chic and posing of New York.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency

Goldin gave her first public slide show as a part of a celebration of Frank Zappa’s birthday at the Mudd Club, probably in 1980. The show and the audience featured many of those whose lives were to be exposed in her later work, including David and Suzanne as well as various New York East Side celebrities including the transsexual artist Greer Lankton and poet Cookie Mueller.

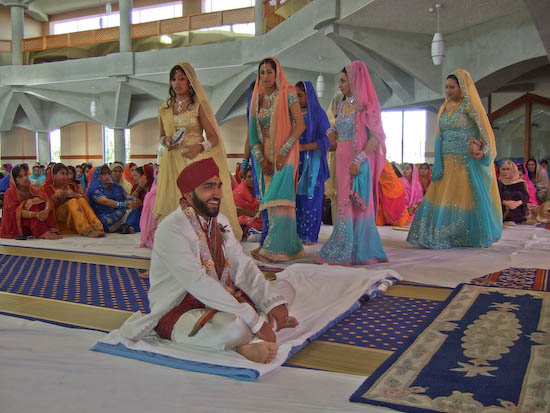

Soon the slide show was expanded and gained a musical sound track and the title title ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’. It continued to evolve over 15 years, eventually containing around 700 slides and running around 50 minutes. The images showed her views on relationships between people – couples of various types – and the different ways in which both men and women constructed their gender roles. The book, published in 1986, had as its earliest image a rather conventional looking group of young people eating cake on the grass of the Esplanade in Boston from 1973 and the latest were from the wedding of her friends Cookie and Vittorio in 1986, but the current slide show includes some pictures up to 1989

Men & Women

Goldin had realised at an early age that she could form strong relationships both emotionally and sexually with both men and women. She and her friends were strongly aware of their gender and in various ways attempted to redefine it. She felt intensely both a need to be loved and a need for independent personal space. The idea of “the struggle between autonomy and dependency” was central to her life and her work in the ‘Ballad’, and it was a theme with almost universal appeal. Even many of the more conventional and stiff-lipped of us at times feel the constrictions of our position. Like her we need to be together but we want to be alone.

Watching the ‘Ballad’

The ‘Ballad’ doesn’t really have a story, being more a series of episodes or themes, announced by changes in the accompanying music. It’s both a celebration and an examination of a subculture crowded with mainly young people in 80s cool playing with drugs, gender, sex and each other. Those who shared her world felt that Goldin captured the essence of the times in that particular milieu. Watching the slides I often felt astonished that someone presumably in more or less the same state as those in the pictures (and often she was in the pictures and in quite a state) had managed to function to even make the work, let alone make it so precisely.

Fifteen years on, I still found it both powerfully moving and at times hysterically funny, though few others in the rapt audience with which I shared it at the Whitechapel Gallery – most of a more similar age to the people in the pictures – seemed to share my amusement. In an art gallery context it tends to get taken in silence as great art, something that there was little chance of in the Mudd club. Goldin made it to be entertainment as well as art.

Wild Women

There are a few funny bizarre pictures, but it was mainly the excruciatingly obvious juxtapositions of the soundtrack excerpts from blues, pop, rock, reggae and opera that make it hard not to laugh. Name an old, sad love song and it’s probably there, together with some more upbeat numbers such as the exultantly angry Wild Women Don’t Have the Blues. The music ranges through Brecht and Dean Martin, Callas, Aznavour, James Brown and Marlene Dietrich to some deservedly unknown names from the 80s.

Technically it seemed amateur by modern standards, with slow slide changes and some annoying seconds of blank screen. There are also some slow fade effects apparently sprinkled with little rationale, reminiscent of low budget ‘audiovisual’ productions of the 1980s – exactly where it started. In a way it was a disappointment to go back for a second view a couple of weeks later and find it was much slicker, and I realised that the gallery had not noticed that one of the projectors had not been working on my first visit.

In fact it I think it still wasnt working as it should, with some images too dim to see properly, and certainly looked amateur and inept compared to her later slide presentations. Some of the dupes used in the seemed rather poor, and had probably deteriorated over the show. Of course, with work shot over a period of almost 20 years, the originals will also show considerable differences with changes in film emulsions. But for gallery showing, transfer to a digital format would have great advantages.

The slide shows, and in particular the ‘Ballad’, are central to Goldin’s work, and the prints on the wall are in a sense secondary, which is difficult for galleries to comprehend and the art world in general tends to see them as a rather inconvenient and hard to market irrelevance. The Balladmuch is a work that deserves more care and professionalism from galleries.

What started as a diversion between sets in punk clubs became a cult and is now finally a museum piece. We first saw it in the UK at the Edinburgh festival, then a couple of years later at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London. The ‘Ballad’ is very much a work of its times, in its clothes, the artefacts and also perhaps the ideas, though some of these remain the material of best sellers. “I often feel“, wrote Goldin “that men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other

almost as if they were from different planets“, a sentiment that sums up several more recent popular psychology books. You can learn rather more from her pictures than you can from them.

Brian and Nan

One of the relationships that runs through the ‘Ballad’ is her own long term one with Brian (the man sitting on the bed in the picture described in the previous section.) It was a relationship that was to end shortly after the picture was taken, possibly in part because Brian had read some of her diaries, with Goldin battered and nearly blinded in Berlin in 1984. One of the most moving pictures in the sequence is a close head and shoulders portrait of her taken at her request by Suzanne Fletcher a month after the attack. It shows her facial bruises and a bloodshot part-closed left eye matching her bright red lipstick as she stares straight at the camera. This and similar images had an important function for Goldin, in persuading her that she should not renew her relationship with him.

Mise en Scène

Goldin’s work impresses by her ability to direct her subjects, to relive her and their lives for the camera as they live it. Some of the pictures are certainly snapshots, but most just look like snapshots, and demonstrate her ability to pick a suitable time and place and to set thing up exactly as she wants them.

She is truly a master (one can’t say a mistress without unfortunate connotations) of mise en scène. Even aspects that appear amateur – such as frames that are not sharp or are damaged by fogging or with strong colour casts are used deliberately to enhance the idea that these are part of a family album. I suspect the couple of reversed slides in the last performance I saw were genuine error rather than design, but they and the noise of the slide changes (along with some rather inept cross fades) all added to the impression of a private amateur showing in someone’s front room. Goldin’s family slides are absorbing to watch (we are all voyeurs at heart) but many like me will be glad to be only a visitor and to sit these events out in real life.

Drugs

After the break-up with Brian, Goldin became more and more addicted to drugs. Many of her friends were also beginning to suffer from continued abuse of their bodies by alcohol and drugs. It made things wors that this came at a time when many of her friends were dying from Aids, and she became involved in photographing a number of them, trying in her mind to keep them alive through photographer, but succeeding only in preserving them on film.

All By Myself

By 1988, Goldin she was in such a bad state that she decided to go into hospital to detox. But there they took her camera away and she didn’t know what to do. When she was transferred to a halfway house, she got her camera back and started to produce an intensive series of self-portraits, taken with available light.

These pictures, together with other self-portraits over the years were later to form the basis of another slide show, called ‘All by Myself‘, (1995-6), with an Eartha Kitt soundtrack. Some critics have found this too saccharine and kitschy. For me the interplay between the searing honesty of some of her pictures and the very different emotional tones and depth of the music makes this one of her most effective works. It’s certainly a piece that makes me warm to Goldin as a person rather than to simply admire her as an artist.

Aids and Memories

Goldin’s idea that her photography is very much a way of keeping memories of people alive is at its most explicit in several sequences dedicated to the memory of friends who have died from Aids, including ‘The Cookie Mueller Portfolio, (1976-90), ‘Gotscho + Gilles. Paris, (1992-3) and ‘Alf Bold Grid‘, that dominated her work in the early nineties.

Goldin has described how she first heard about Aids in 1981, when Cookie Mueller read an article about a new illness from the ‘New York Times’ to a group including Sharon, Cookie’s lover, David Armstrong and a few others. They all laughed it off, sure it wouldn’t affect them, but only the following year one of David’s lovers was the first of many friends to die from it.

Mueller, according to John Waters, the first to recognise her potential as a film actress (and director of her first film, “was a writer, a mother, an outlaw, an actress, a fashion designer, a go-go dancer, a witch-doctor, an art-hag, and above all, a goddess.” Born in 1949 in Baltimore, Cookie and became good friends with Goldin in 1976, and she photographed Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding in New York in 1986. The portfolio is a montage of pictures that follow Cookie from the fullness of her life to her corpse in the casket in 1989.

Gilles was her French art dealer. She photographed him with his lover while still in good health and then made a fine picture of the couple in hospital. Alf Bold was a German friend who also died of Aids.

Greer Lankton

Greer Lankton, (1958-1996), was born the son of a Presbyterian pastor and had a sex-change operation at the age of 21 in 1979. She appears in many fine pictures by Goldin and was well known for her dolls and sculptural installations, including a life-sized doll of the famous fashion columnist and editor Diana Vreeland (1903-1989) who worked for both Harpers Bazaar and later Vogue (and discovered Andy Warhol.) Greer suffered from alcohol and drug addiction and anorexia. The section of pictures of her in ‘The Other Side’, is probably the most effective part of this book.

More of a Drag

In 1990, Goldin returned to photographing drag queens, photographing again in New York clubs. However, by this time the subject had lost its frisson. Drag was no a normal aspect of the scene, no longer an esoteric fringe, and such studies were now almost a standard subject for many if not all student portfolios. With a few exceptions, such as a fine action picture, ‘Jimmy Paulette on David’s bike. NYC 1991’ where her flash catches the two riders in centre frame against a blurred background, the results (also shown in ‘The Other Side’) were disappointing.

Tokyo Love

Her collaboration with the Japanese photography Nobuyoshi Araki was of considerably more interest. Araki is an extremely prolific photographer, who has also produced visual diaries for many years. Goldin met him in 1992, and returned in 1994 to work together on the book ‘Tokyo Love‘. Their work alternates throughout the book, mainly in double pages, but with some sets or four or six pictures. Araki contributes studio portraits of young adolescent girls who are in their first Tokyo spring.

Goldin’s work also looks at young people, but ranges more widely, with a great picture of the ‘Honda Brothers with falling Cherry Blossoms’ swirling like lilac snowflakes as they stand in the street, as well as many people in clubs, homes and elsewhere. Goldin found young Japanese who reminded her of a younger self, with the same attitudes, the same beliefs she had as a teenager. Like her they had “transcended any definitions of hetero or homosexual.” She found the project was like a journey back into an age of innocence, “before my community was plagued by Aids and decimated by drug addiction” (Tokyo Love.)

BBC Film

Goldin had started shooting movie film before she took up photography, and slide show works such as the ‘Ballad’ can perhaps be seen as a film shot as stills. In 1996 she worked with the BBC on a TV programm, ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror‘, shooting most of the interviews, including those with Gotscho, Sharon Niesp and her girlfriend, and Greer Lankton. Some of her own early footage from Boston years was also included.

In an interview for ‘Thirteen Online’ with Kathy High, she made clear that she was not happy with the way the BBC’s middle-class Oxford-educated director removed the film from reality, including scenes that would appeal to a British audience but did not represent how things had been. Bringing a 16mm film crew and lights into relatively intimate situations also falsified them, changing things completely from how she really lived and worked. To her disappointment, much of the footage she herself shot for the film – including almost all of that related to Aids – was never used.

I can’t help thinking that a film made with Goldin herself in charge would have had a far more lasting interest, and that the BBC missed a great opportunity in making a BBC film rather than getting a Goldin movie, which would have had a much greater interest. Their director may have made a ‘better TV programme’ with higher production values but this was at the expense of the rigorous realism and often-uncomfortable truth central to Goldin’s work.

She also found the concept of a film limiting, in that it is forever stuck at the particular state and point of time at which it was edited. With the ‘Ballad’ and other slide shows that she has updated them over the years. A year after the film was made, the lives of many of the people featured had changed – Greer for example was dead, but the film doesn’t change to reflect that.

More recent work

Goldin’s photography around the turn of the century fell into two areas. She has continued to work with couples, but has concentrated on photographing their more intimate moments, producing series of images including ‘First Love’, ‘French Family’, ‘The Boys’, and ‘Valerie and Bruno’. Pictures from these sequences, along with some others were combined in her slide sequence, ‘Heart Beat, 2001’, a passionate hymn to love, with a John Taverner soundtrack setting of the ‘Kyrie Eleison’ (Greek for ‘Lord Have Mercy’), part of the traditional Christian mass, performed with amazing vocal agility and intensity by Björk.

Goldin has also photographed scenes without people, including landscapes, interiors, skies, cityscapes, under the title ‘Elements’ (presumably a reference to Earth, Air, Fire and Water) which are often curiously abstract. A second series ‘Relics and Saints’ concentrated as its name suggests on religious imagery found in churches, grottoes and catacombs.

Working for Prints

In the ‘Ballad’, the slide presentation was clearly the primary work, with the prints and book illustrations allowing you to see the individual frames at leisure (some only flash briefly on screen.) Recently there has been a shift in the balance between prints and slide presentations with the prints becoming primary. Portfolios such as ‘Cookie Mueller’ used a grid of smallish prints, but her more recent work is uses sequences or groups of very large (1×1.5 metre) Cibachrome colour prints, and the projections using them appear secondary.

Goldin is one of a few well-known fine art photographers who have made some original prints available at affordable prices. At many of her shows she has sold limited edition moderately sized Cibachrome at a reasonable price (75UK pounds plus sales tax at her London show) with proceeds often going to Aids charities. She still remembers the times when she was hard up and interested in photography.

Conclusion

Thirty five years after her first Boston pictures, Nan Goldin is still photographing, still showing us how the world looks to her, letting us get inside, get insight into the life led by her and her friends. It is a remarkable body of work, even if occasionally I feel a little uncomfortable watching.

WEB LINKS

NAN GOLDIN

Artnet: Goldin’s story by Mia Fineman

Good feature with illustrations.

Centre Pompidou: Around Nan Goldin

Informative illustrated site from the Centre Pompidou (English version.)

ClampArt

Eight pictures by Goldin, including several self portraits

Culture Vulture: Fraenkel Gallery 2002

Review on ‘Culture Vulture’ of a show from 2002, illustrated by pictures from 1999 and earlier.

Digital Journalist: Goldin on Aids

Cookie at Vittorio’s casket, NYC, Sept 16, 1989 and ‘Cookie in her casket, NYC, November 15, 1989, with a link to a statement by Goldin.

Ikon Gallery

Six pictures by Goldin.

Stedelijk 1997

Pictures include Cookie’s Wedding and the Honda Brothers.

Tate Gallery

Six images available on line including ‘Greer and Robert on the bed, NYC (1982)’ and ‘Nan one month after being battered (1984)’.

Whitechapel Gallery: Nan Goldin – Devils Playground

Text and one images from her 2002 London show (also shown in Paris).

TEXT ONLY

Artforum:

Nan Goldin talks to Tom Holert (2003) A detailed interview on the 1980s.

Thirteen Online

Transcript of a telephone interview with Goldin about her BBC film ‘I’ll be your Mirror.’

Observer

Sheryl Garratt talks to Nan Goldin about love, survival and loss

OTHER WEB LINKS

Emotions & Relations

A ‘Boston School’ show in Germany. Nan Goldin, David Armstrong, Mark Morrisroe, Philip-Lorca diCorcia and Jack Pierson -text and two pictures.

Greer Lankton

A page with examples of her work.

Cookie Mueller Dreamland Gir

A site dedicated to the memory of this multi-talented woman.

David Wojnarowicz,

Friend and collaborator with Goldin who died from AIDS in 1992. Text and images.

Peter Marshall 2007