On Monday, a statement by Assistant Commissioner John Yates was issued by the Metropolitan Police Press Bureau which details the advice sent by him to all MPS officers and staff. It clearly repeats the tone of the advice contained in the Home Office circular in September, and I’ll repeat it in full at the end of this piece.

Photographers may even feel it is worth carrying a copy with them, but I think should you do so that you should make use of it tactfully if you are approached by the police or even police community support officers while taking pictures. If you adopt a confrontational or evasive attitude when you are questioned it will only serve to escalate the situation – and can be a trigger for some very inappropriate behaviour by PCSOs and police, as I think two reports from the Guardian clearly demonstrate.

One was a deliberate attempt by Guardian reporter Paul Lewis to get himself harassed while taking what were misleadingly described as “Casual shots of London’s Gherkin“and the second was the considerably more serious and inexcusable harassment of Italian art student Simona Bonomo at Paddington, described in a story and video “Italian student tells of arrest while filming for fun” a month ago which they published last Tuesday.

Had Lewis, when approached by security staff told them – or the off-duty police officer who came along – he was a Guardian journalist working on a story about the harassment of photographers while photographing buildings and shown them his press card there would of course have been no story. But it seems pretty clear to me from his own video that he was behaving at best rather curiously and in a way that was clearly intended to arouse suspicion. If you poke the animal with a stick you should really be hardly surprised that it bites.

Of course the response of the police was stupid and in some respects over the top, but hardly unexpected. The least defensible part of their response seems to have been the stop and search carried out on the photographer who was recording the event from a distance with a telephoto lens, for which there appears to be no remotely believable justification.

I have considerably more sympathy for Simona Bonomo, particularly as she was both assaulted with obviously unreasonable and entirely unnecessary force by police officers and was then stitched up with a fixed penalty fine of £80 for a public order offence of which she is obviously innocent.

But again I think it was an incident that need not have happened, and that the Guardian’s report of it is again in some respects misleading though they deserve credit for bringing it to public attention. Their headline that says she was arrested “while filming for fun” is incorrect. Although her first rather offhand response to the PCSO was to say that she was filming “just for fun” it is clear that this was not true, both from the actual video footage which starts with her filming security cameras (which probably alerted the PCSOs) on the buildings and what she says later on in her exchange with the PCSO. She is an art student at a London university and was working on a project on surveillance (and rather painfully this incident produced some only too real material for it,) Had she made that clear when she was first approached the situation would almost certainly not have escalated as it did – the PCSO himself says so on the video.

Of course the police – and the PCSO – got it seriously wrong. But while photographers should stand up for their rights, we should also generally be open and clear about what we are doing. If anyone asks me why I’m taking pictures – by a member of the public or the police force – I try to explain briefly and politely (usually but not always entirely truthfully), and when appropriate show my press card or offer my business card.

Of course sometimes you need to explain to people about your rights – and for some years my camera bag contained a personal letter from the Met which clearly explained that like all other photographers I had a right to take photographs on the public highway which sometimes came in handy (and arose from a rather unpleasant run-in I had with two officers in the ’90s.) But it’s generally more effective to do so in a polite and reasonable rather than a confrontational way. Experience tells me that arguing the law with the police at street level is unlikely to be productive – if they don’t know it they certainly won’t admit it.

Back when I taught photography – mainly to rather younger students than Simona Bonomo – we advised students how to work in public, and in particular that telling people who asked that you were “working on a project for your photography course” was often a good way to get their cooperation. I know a number of working photographers who still sometimes use this excuse – just as the great ‘Eisie’ – Alfred Eisenstaedt – would sometimes assure the people he was photographing that he was “just an amateur.”

Some of my students did occasionally decide to work on projects that might be contentious in some way and it was then my job to discuss the possible risks with them, and at times suggest other ways of approaching the subject. For a project like this I would have provided a student with an official letter signed by the head of department “to whom it may concern” giving brief details of the student and the project with a request for their cooperation and of course a phone number they could ring if they had any concerns, and have asked the student to ensure they had this with them when working outside college on the project.

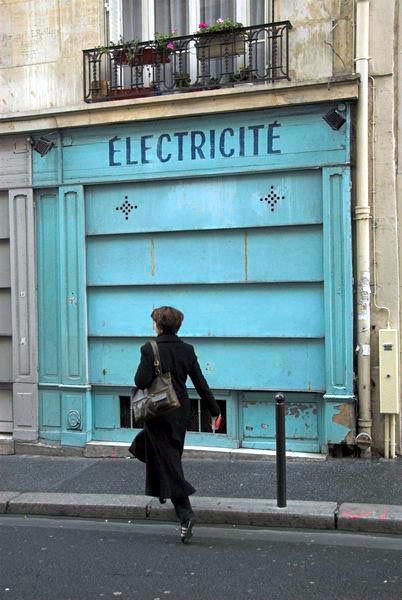

Paddington Basin, 2004. Peter Marshall

I’ve photographed around new developments in Paddington and the surrounding area on several occasions over the years without permissions or problems, though I was approached by a security man on one occasion. I told him what I found interesting in the particular view I was taking and he went away thinking I was mad but harmless. I suspect that much of the land here is actually private – like so many new developments, but I wasn’t asked to stop taking pictures.

Anyway, here’s the statement from the Met in full:

Statement by Assistant Commissioner John Yates

John Yates, Assistant Commissioner Specialist Operations, has today reminded all MPS officers and staff that people taking photographs in public should not be stopped and searched unless there is a valid reason.

The message, which has been circulated to all Borough Commanders and published on the MPS intranet, reinforces guidance previously issued around powers relating to stop and search under the Terrorism Act 2000.

Guidance on the issue will continue to be included in briefings to all operational officers and staff.

Mr Yates said: “People have complained that they are being stopped when taking photographs in public places. These stops are being recorded under Stop and Account and under Section 44 of TACT. The complaints have included allegations that people have been told that they cannot photograph certain public buildings, that they cannot photograph police officers or PCSOs and that taking photographs is, in itself, suspicious.

“Whilst we must remain vigilant at all times in dealing with suspicious behaviour, staff must also be clear that:

- there is no restriction on people taking photographs in public places or of any building other than in very exceptional circumstances

- there is no prohibition on photographing front-line uniform staff

- the act of taking a photograph in itself is not usually sufficient to carry out a stop.

“Unless there is a very good reason, people taking photographs should not be stopped.

“An enormous amount of concern has been generated about these matters. You will find below what I hope is clear and unequivocal guidance on what you can and cannot do in respect of these sections. This complements and reinforces previous guidance that has been issued. You are reminded that in any instance where you do have reasonable suspicion then you should use your powers under Section 43 TACT 2000 and account for it in the normal way.

“These are important yet intrusive powers. They form a vital part of our overall tactics in deterring and detecting terrorist attacks. We must use these powers wisely. Public confidence in our ability to do so rightly depends upon your common sense. We risk losing public support when they are used in circumstances that most reasonable people would consider inappropriate.”

++++

The guidance:

Section 43 Terrorism Act 2000

Section 43 is a stop and search power which can be used if a police officer has reasonable suspicion that a person may be a terrorist.

Any police officer can:

– Stop and search a person who they reasonably suspect to be a terrorist to discover whether they have in their possession anything which may constitute evidence that they are a terrorist.

– View digital images contained in mobile telephones or cameras carried by the person searched to discover whether the images constitute evidence they are involved in terrorism.

– Seize and retain any article found during the search which the officer reasonably suspects may constitute evidence that the person is a terrorist, including any mobile telephone or camera containing such evidence.

The power, in itself, does not permit a vehicle to be stopped and searched.

Section 44 Terrorism Act 2000

Section 44 is a stop and search power which can be used by virtue of a person being in a designated area.

Where an authority is in place, police officers in uniform, or PCSOs IF ACCOMPANIED by a police officer can:

– Stop and search any person; reasonable grounds to suspect an individual is a terrorist are not required. (PCSOs cannot search the person themselves, only their property.)

– View digital images contained in mobile telephones or cameras carried by a person searched, provided that the viewing is to determine whether the images contained in the camera or mobile telephone are connected with terrorism.

– Seize and retain any article found during the search which the officer reasonably suspects is intended to be used in connection with terrorism.

General points

Officers do not have the power to delete digital images, destroy film or to prevent photography in a public place under either power. Equally, officers are also reminded that under these powers they must not access text messages, voicemails or emails.

Where it is clear that the person being searched under Sections 43 or 44 is a journalist, officers should exercise caution before viewing images as images acquired or created for the purposes of journalism may constitute journalistic material and should not be viewed without a Court Order.

If an officer’s rationale for effecting a stop is that the person is taking photographs as a means of hostile reconnaissance, then it should be borne in mind that this should be under the Section 43 power. Officers should not default to the Section 44 power in such instances simply because the person is within one of the designated areas

So the Met at least have clear advice on the law – though it remains to be seen how well this will permeate down to street level. I hope someone has given a copy to the guys in the City of London force too, and elsewhere around the country.