2006

In 2006 I was in Paris in November for the three days of Paris Photo but spent roughly a week there staying at a very pleasant (and cheap) hotel towards the north of the 9e. It was a healthy 25 minutes walk from Paris Photo and a little closer than that to the Gare du Nord, making it handy for those of us who travel on Eurostar (and fortunately that November we didn’t have snow, so the Eurostar was working well.)

Paris

I wrote a few pieces related to the show for the company I was then working for, About.com, which have long disappeared from the web, but the first real post I wrote for this blog, on Friday, December 1st, 2006 at 11:51 pm was also on Paris Photo. It was only a short note, but it ended with the sentence:

But fortunately, there was much more in Paris than Paris Photo.

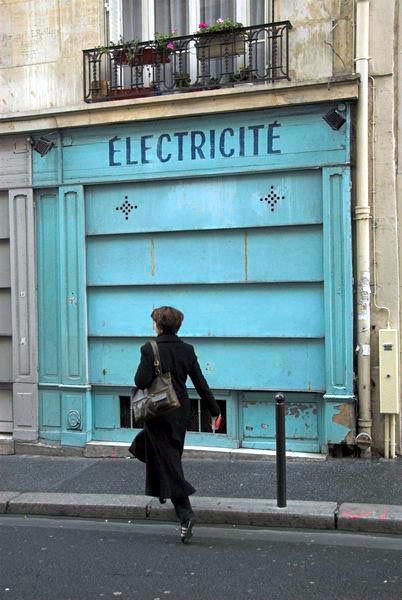

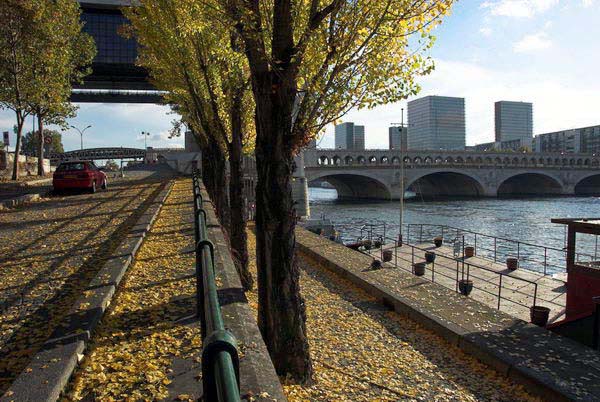

You can get some idea what that more was (though without the food and wine) from a set of pictures I put on the web shortly after, Paris: November which is now linked in from my new Paris site. These pictures were taken with a Nikon D200 in Paris and Stains, just to the north of the city.

Stains

On the revised front page of my Paris Photos site you’ll find a rather untidy list of links to most of the sets of Paris pictures that I have on line. There are a few more sets almost ready to add, but rather more waiting until I have time to do more scans.

An Early Amateur

Luminous Lint, an extensive collection of material assembled on-line by Alan Griffiths, now based in Canada, has an interesting album of photographs from An Unknown Street Photographer in Paris, 1896, curated and introduced by John Toohey who now owns the ‘small, olive green Kodak album with the handwritten inscription on the inside cover, “Paris, 1896“‘. It was thus taken when the Kodak revolution which brought photography to the middle-class masses had just begun.

Although I’ve not studied the work at the length that Toohey has (nor seen the other roughly 60 pictures not included in the generous selection on the site), I find his introduction to the album far-fetched. Looking through it I don’t think we can read in any great intentions by the photographer, although certainly it is produced with someone who at least occasionally had an idea of what they were trying to do. But I remain convinced that the more interesting accidents of the work are simply accidents, not least because the viewfinder on these cameras would hardly allow the kind of control that he suggests. Whenever you photographed anyone close to the camera you were likely to get pictures without heads or with only a part of them in the picture, and while you were concentrating on taking your picture on the street, people were only too likely to walk partly into them as you pressed the button.

Of course such accidental cuttings of the subject by the edge of the photograph were quickly recognised as a part of the machine’s syntax, and it has been suggested that they had some influence on the painters of the day, such as Degas, although similar effects also were to be found in some of the earlier Japanese artworks that more certainly affected artists of the late nineteenth century.

I grew up when family pictures were still taken on cameras not much different to the 1895 Pocket Kodak, larger but essentially similar models making small ‘snapshots’, though by then it was possible to get larger ‘en-prints’, but most of those in the albums were carefully posed, even if intention and result were even then not always close. In those distant days a 12 exposure film usually did families like mine for a couple of annual holidays (in Worthing or Lowestoft rather than Paris) and we relied postcards for the sights rather than photographing them ourselves.

Amateur photography was of course a craze of the 1890s, and by 1898 there were estimated to be around 1.5 million roll film cameras like the Pocket Kodak in use, with clubs springing up to support them. And there is good evidence that this unknown photographer was a part of one of these informal or formal groups that sprang up, as in some pictures we see seriously suited men with cameras. Most likely he looked rather like one of these, although Kodak from the start marketed their cameras to women also, and this small and lightweight camera would fit readily as into a handbag as into a large jacket pocket. Of course many soon lost interest in photography and took up that other craze of the age, the bicycle, which also features strongly in these images (and even a tandem!) Some Camera Clubs even voted to become Cycle Clubs, leading Alfred Stieglitz to comment in 1897 “Photography as a fad is well-nigh on its last legs, thanks principally to the bicycle craze.”

It was also obviously the album of someone with a serious interest in photography, as well as the income to be able to afford to indulge it. There are 92 pictures in the ‘Paris 1896’ album, showing the use of at least 9 rolls of the size 102 film which gave 12 exposures (it was one of the first models to have a red window to read markings on the back of the paper film backing.) Probably he (or, less likely, she) took more, but not many more, as even these small 1.5×2″ pictures were relatively expensive and few other than outright technical failures were discarded.

The Pocket Kodak at around 51 x 76 x 102mm was reasonably compact cameras even by today’s standards, with a weight of around 170 grams, could as the name suggests be carried in a pocket. But it’s real selling point was ease of use – as the Kodak slogan said, “You press the button and we do the rest”.

There was nothing to set – focus was fixed, the single shutter speed was “instantaneous” (usually around 1/100s) and so long as you kept to the instruction only to work on sunny days and held the camera steady it would work. The hardest thing was to remember to wind on the film after each exposure and so avoid double exposures.

Of course other things could go wrong and very often did. The viewfinder was a small window on the top of the box which you looked into as you held the camera steady against your stomach, seeing a clear and bright but tiny image – which was usually rather less than would appear in the picture. Accurate framing was impossible (and a concept that hardly existed before the invention of the ‘miniature’ camera using 35mm film.) If you took pictures from a sitting position, unless you thought instead to rest the camera on your knee, it would probably also appear in your picture.

There is no doubt that this is an interesting album, but I think it is best to see it for what it is, rather than to drag in the names of Walker Evans, J H Lartigue or Andre Kertesz. And if you are going to do so, why stop there; surely the wishful mind could glimpse the harbinger of Cartier-Bresson and Friedlander here too?