this afternoon I went to an interesting presentation, Radical Archives for the future: networks and collaboration organised by Four Corners in Bethnal Green. Four Corners, which began as an independent film workshop in 1973, inherited the archives of Camerawork (and the Half Moon Photography workship), which published one of the most interesting photographic magazines of the 1970s, devoted to radical left practice in photography and including the work of people like Paul Trevor and Jo Spence. And you can find out more at their recently set up archive.

Camerawork was a confusing title for a photography magazine, as probably the best-known (and argualbly the most beautiful) publication in the whole history of photography was Camera Work, its 50 issues produced in stunning photogravure from 1903 to 1917, edited by Alfred Stieglitz, with its last two issues dedicated to the then novel modernist approach of Paul Strand. But Camerawork, founded in 1976, was in its early years a powerful influence on many young British photographers, and copies are held in most major libraries with an interest in photography as well in a box on the top of my bookshelves.

Camerawork somewhat lost the plot at the end of the decade (see Paul Trevor’s review of the book, The Camerawork Essays), when photography saw a huge and highly destructive debate over theory and practice, which essentially debilitated UK photography for the next decade or two, though Camerawork struggled on, at least on the Roman Road into the following century, but with little relevance in its later years to current photography. Four Corners then inherited its premises and its archive.

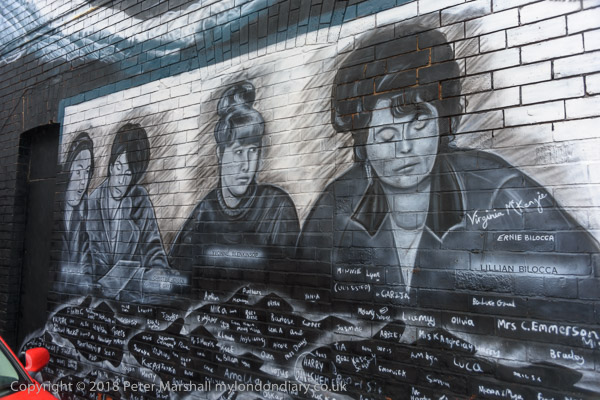

I probably should have written earlier about the Radical Visions show ending at Four Corners now, which looked at Community photography and in particular the contribution to this of Camerawork, but somehow it is hard for me to take too seriously a show where the great majority of images on the wall are also on the shelves behind me as I write. But of course I do realise that there are generations now unaware of its history.

I was a subscriber to Camerawork from almost the start, with issues from No 2 winging their way to me by post, and these accumulated in my personal archive until I cancelled my subscription when I thought they magazine had abandoned photography. The first issue, which I think I bought in the gallery, seems to have disappeared, but it impressed me enough to subscribe.

Active in photography since around 1971, I have over the years built up a considerable archive or magazines, books and of course photographs, mainly my own, but also by others I worked with in various ways. It’s a not inconsiderable archive, probably around a million physical ‘documents’ (negatives, slides, prints, magazines, books etc), but rather more digital files.

A small amount of this material is now duplicated in more official and more organised archives – such as those of the Museum of London and Bishopsgate Institute – but most is not. A much larger amount, particularly of my own images is much more available to researchers and others with any interest on the web – now approaching a quarter of a million images. Most days I add a batch of perhaps 20 or 100 images to that on-line archive.

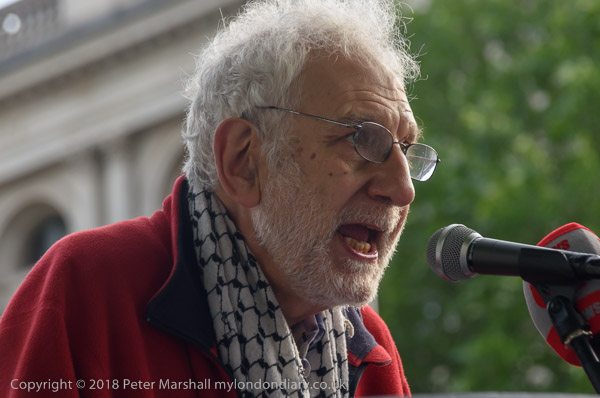

The presentation and discussion at Four Corners was largely dominated by professional archivists (along with some unpaid amateurs running archives) whose approach I think is not always helpful. The audience included others involved with archives, and academics, along with a few photographers.

Photography for me is at its very basis a medium that arose from the possibilty of the essentially infinite reproducibility of the photographic image. Why Talbot’s negative-based process was such a great step forward over the in some ways superior Daguerreotype. Later it became the medium for the printed press, enabling the mass production of books and magazines. Many of the most iconic photographs were produce by photographers who were working for the printed page, and the books and magazines, not the photographic print are the true expression of their work in the medium.

Unfortunately, largely by by transference from the art market too many fetishise the photographic print, and in particular the idea of the vintage print. Had photographers like Edward Weston been able to use computers and make prints with the control that these enable I’m sure they would have jumped at the chance. I’ve always felt that – in the past, and beginning with Anna Atkins and W H F Talbot’s ‘Pencil of Nature’ that photographs belong in books – and more recently that their true home is also in digital publication. Certainly I don’t dispute the value of a fine print – I learnt to print from Ansel Adams (though from the first and best edition of his Basic Photo series) and from criticism by Raymond Moore at a time when photographic printing was seldom taken seriously in the UK and ‘soot and whitewash’ was in vogue (and in Vogue.)

It often annoyed me when I taught photography that I had to make students go to study ‘first hand’ at the V& A or exhibitions, when the real authentic experience of a photographer such as Robert Capa or Gene Smith was in magazines such as Life or books which we had in the college library (or my personal collection).

Photographic reproduction in books has improved to the level that it is now often at least as good as that of original prints. Back in the late 1970s I pissed off Lewis Baltz when he was examining the page proofs of ‘Park City’, by giving him my opinion that they were better than his own photographic prints. It was clearly true, but certainly not politic.

I’ve had long arguments over the years with some professionals in the world of archiving who have discounted the use of digital files for archiving. At least one such professional ended up by researching the writing of digital files not as digital files but by printing them out in a binary format using carbon inks on acid-free paper, arguing that only these would be available to generations in the extreme future.

We need to get real about archiving. The rate at which we produce stuff means that only a very limited selection can possibly be save in its original print or poster format for the future. Digitisation enables us to save a rather larger selection, but still requires careful consideration of what is worth saving and makes easier the careful captioning, particularly in metadata, of what is saved. Metadata is vital for the way it enables us to find material, particularly visual material that has litte or no textual element.

Digital archiving has many advantages, enabling the same record to be classified in multiple ways and facilitating both simple and complex searches, particularly on text in captions and metadata, but increasingly on image elements as greater computing power enables matching of faces or other elements.

I have a sneaking suspicion that what will be of most use to future generations and historians will not be the archives we were discussing, but the residues of the internet, and of commercial services such as Facebook and Instagram, – and perhaps even websites like my own, such as My London Diary, London Photos and Still Occupied – A view of Hull. And I’m slowly working through my own output over the years, producing digital images from those negatives and transparencies I feel worth keeping, and thinking of ways to provide those digital images with a future after the photographic materials have decayed or gone to landfill.