London’s Canal Walk: On Saturday 26th May 2007 I walked across London together with my wife and older son on canal towpaths from Mile End in the east to Old Oak Lane in the west, from where we made the short walk to Willesden Junction for a train towards home.

I’d walked and cycled along many shorter sections of these canals before, but this was the first time I’d done the whole roughly 12 miles in a single stretch. Most of the way we kept to the towpaths, but there are two tunnels around which we had to detour on roads, and a few places where walking along a road was more convenient than using the tow path, particularly around Little Venice.

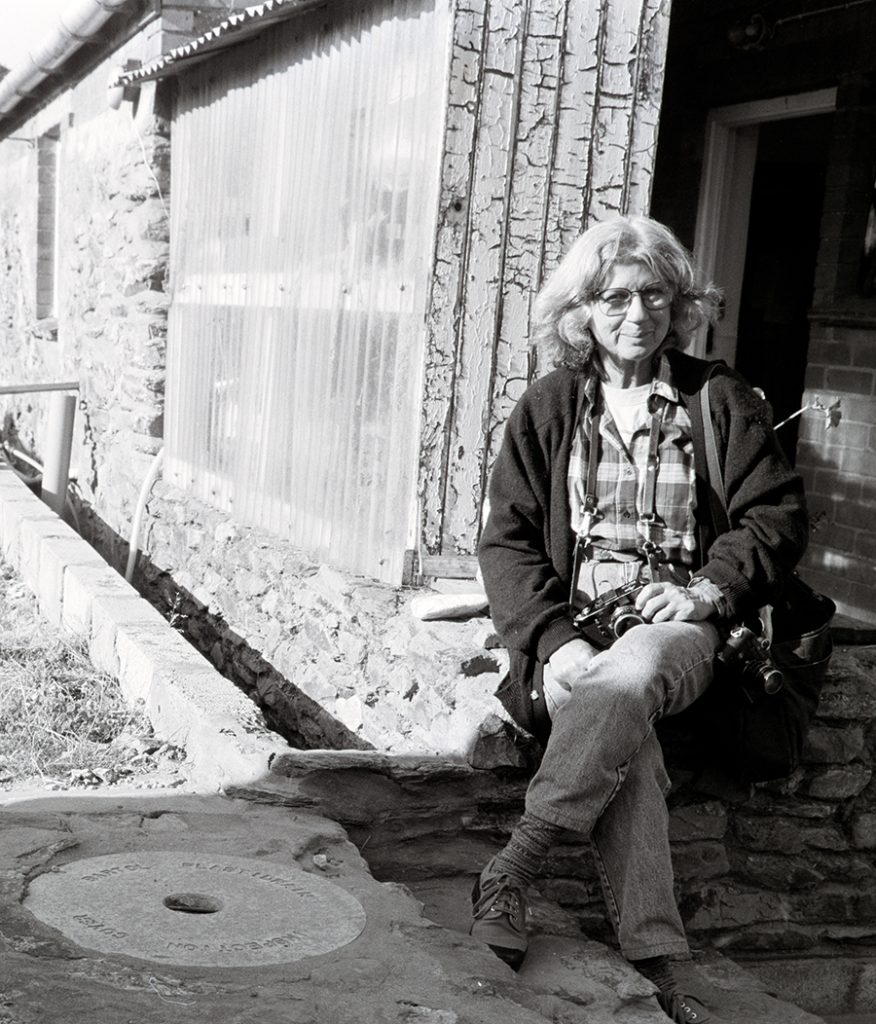

Probably the definitive book on English canals was written by a photographer, Eric de Maré, (1910 – 2002), one of a now largely forgotten generation of British photographers, and illustrated with many of his fine photographs, as well as some by others. He was one of the finest architectural photographers of the mid-20th century and also someone whose popular Penguin book ‘Photography’ published in 1957 introduced many of us to the history, techniques and aesthetics of the medium. Others since have looked better on the coffee table but have lacked his insight.

de Maré and his first wife lived on a canal boat for some years and travelled around 600 miles along them while writing and taking the pictures for the book ‘The Canals of England’ published by Architectural Press in 1950 which remains the definitive publication on our canals, though in some obvious ways outdated. The canals – which had played an important part in the war effort – had been nationalised under the National Transport Act on 1st January 1948 and part of the book is an impassioned plea for the UK’s transport policies to be revised to update the system and make fuller use of our great canal heritage.

But of course that didn’t happen, thanks to huge road transport lobby, and instead of canals similar to some in the continent we got motorways. The canals were encouraged to bring commercial traffic to an end, and with a few isolated examples most was finished by 1970 with the canals being given over to leisure use.

Not that de Maré was against leisure use and his work actively promoted this for many of England’s narrow and more rural canals as well as making an argument based on the commercial possibilities of schemes such as the ‘Cross or Four River Scheme’ proposed earlier by a 1906 Royal Commission for wide high volume commercial canals linking Bristol, Hull, Liverpool and London with the Midlands cities of Birmingham, Nottingham and Leicester.

The book came out in a second edition in 1987 and copies of both are available reasonably priced secondhand – my copy of the first edition with a handwritten dedication from de Maré was at some point marked by a bookseller’s pencil for 6d but I think I paid just a little more. I can find no individual website showing more than a small handful of his pictures – though you can see many by searching for his images online.

It’s still interesting to walk along by the canals in London, and easy to do in smaller sections – or to add a little at either end should you want to and perhaps walk from Limehouse to Southall or Brentford. I didn’t write much about the walk in 2007, but I’ll end with what I did write back then – with the usual corrections.

On Saturday I accompanied Linda and Sam on a walk along some of London’s canals, from Mile End on the Regent’s Canal and along that to join the Grand Union Paddington Branch at ‘Little Venice’, and west on that to Willesden Junction.

When I first walked along the Regents Canal I had to climb over gates and fences to access most of it. The towpath was closed to install high voltage lines below it, but even the parts that were still theoretically open were often hard to find and gates were often locked. The public were perhaps tolerated, but not encouraged to walk along them.

Now everybody walks along them and there are those heritage direction posts and information boards that I’ve rather come to hate. And from this weekend, you no longer even theoretically need a licence to cycle the paths – though mine is still in my wallet, several years since I was last asked to show it.

Now, as walkers, the constant cycle traffic on some sections has become a nuisance. And although most cyclists obey the rules, riding carefully, ringing bells and where necessary giving way, we did have to jump for safety as one group chased madly after each other, racing with total disregard for safety.

But for the rain – the occasional shower at first, later settling in to a dense fine constant downpour, it would have been a pleasant walk.

Many more pictures on My London Diary

Flickr – Facebook – My London Diary – Hull Photos – Lea Valley – Paris

London’s Industrial Heritage – London Photos

All photographs on this page are copyright © Peter Marshall.

Contact me to buy prints or licence to reproduce.