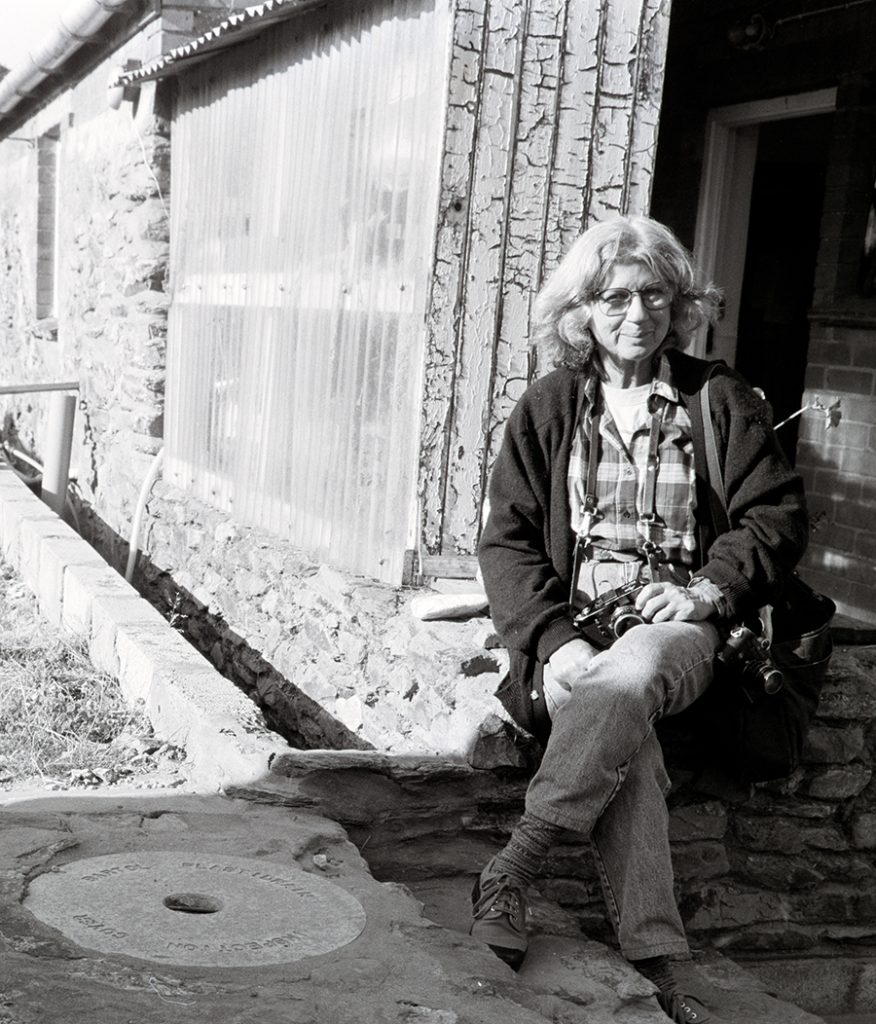

I didn’t really know Joan Liftin who died recently well, but met her when I attended a workshop led by her husband, Charles Harbutt (1935-2015) at Duckspool in Somerset in the 1990s. I was impressed by some photographs she showed there and both she and Charlie were sympathetic and made helpful criticisms about my own work as well as expressing some views on photography which influenced me. Later she sent me a copy of her first book, ‘Drive-Ins‘ which I reviewed for the photography site I was then running for About.com, long defunct.

I heard about her death on The Eye of Photography, where you can read an obit by her friend, the photographer Brigitte Grignet, though unless you are a subscriber you will not be able to see more than a couple of her photographs. But you can see more on Liftin’s web site, which has a few pictures from each of her three books.

There is a lengthy podcast interview with her on ‘Right Eye Dominant‘ where she talks at length about her life and career at Magnum, ICP and more, working with almost every photographer whose name you will know. The sound is a little rough but her character which attracted me really comes across. Close to the end she talks a little about Harbutt and his work. You can also hear her talking on the B&H Photography Podcast. There is a written interview with her on Visura magazine, which in many ways I prefer to a podcast, though it was good to hear her voice again.

Harbutt played an important part in my own photography, particularly through his book ‘Travelog‘ published by MIT in 1973. This was one of the first photography books I bought and opened my eyes to different ways of working. His workshops were legendary, and it was one of those which inspired Peter Goldfield, who I met in the 1970s to leaving Muswell Hill where he had set up Goldfinger Photographic above his pharmacy in Muswell Hill and set up the photography workshop at Duckspool and I wrote about this at the time of Peter’s death in 2009.

Liftin’s web site also has links to a post in the NY Times archive, Moving Freely, and Photographing, in Marseille, with text by Rena Silverman and 16 photographs, though again access may be limited if you are not a subscriber. There are also links to some other features on her Marseille book on her site.

Liftin wrote an introduction to The Unconcerned Photographer published in 2020 which includes the text of a lecture given by Harbutt in 1970 which first publicly expressed his views on photography.