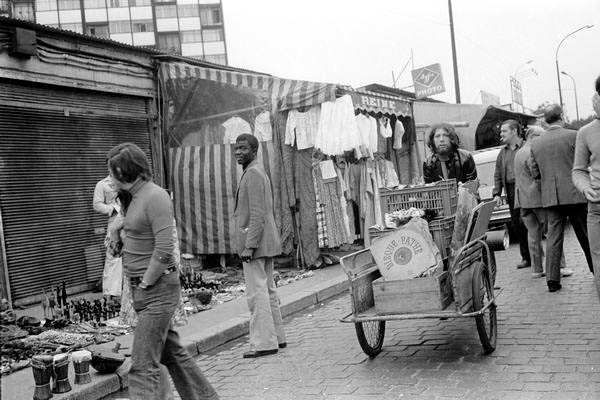

Armistice Day in Paris: On Tuesday 11th November I was in Paris, having gone there to attend Photo Paris which was opening the next day, but more to go to the many other photography shows taking place in the city that month, both in the Mois de la Photo and the much larger official fringe as well as many other shows in the City not a part of these.

But Armistice Day is a Bank Holiday (Jour Férié) in France, and though that month Paris was full of photography, all of the galleries were closed for the day, so Linda and I mainly spent the day walking around some of our favourite parts of Paris – and of course I took some pictures.

We did a lot of walking most days of our visits to Paris, as most of the exhibitions only opened around the middle of the day and we had breakfasted and were out of our hotel by around 9am.

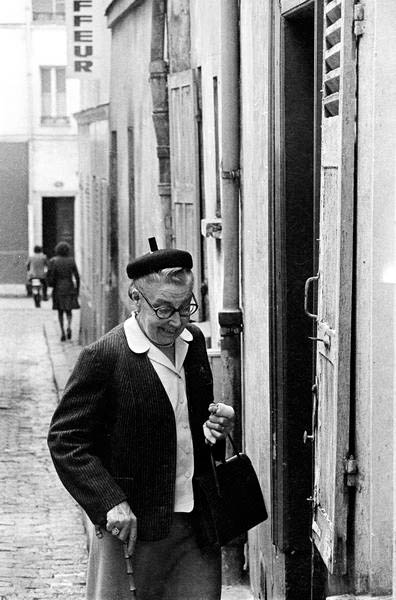

We’ve always enjoyed walking around Paris. On our first visit together we’d done most of the tourist things, but when we returned for a longer stay in 1973 we walked virtually all of the walks in the old Michelin Green Guide – rather more of them than in later editions.

In more recent years we’ve often been guided by the incredibly detailed ‘The Guide to the Architecture of Parish’ by Norval White, with its 58 walking tours which covers the whole of the city, as well as some downloaded from the web, and one very special guide, Willy Ronis (1910-2009).

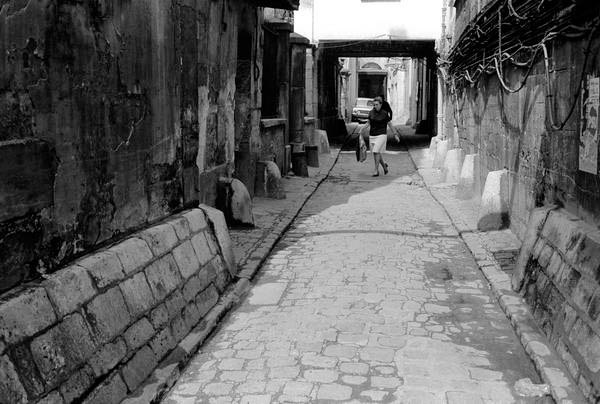

Not of course quite in person, though I did meet him once when he came to talk in London, but following his 1990 ‘la traversée de Belleville’, a slim volume recording his show at the bar Floreal where I was given a copy of the book on a visit during this trip. Much of the route was already familiar to me, but we managed to follow his route precisely for our first time on our last day of this 2008 trip.

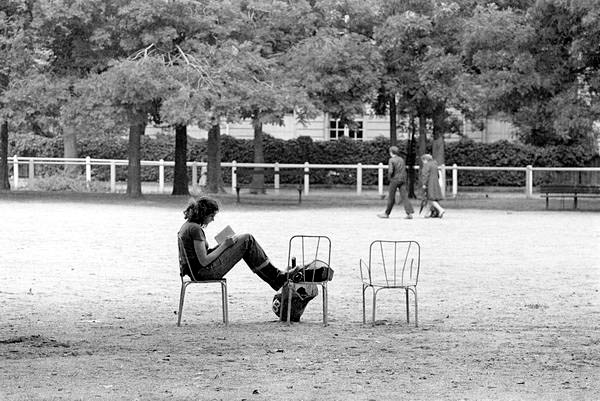

On Armistice Day 2008 we left our hotel and wandered around the nearby area in the 9e and 10e in the north of Paris be taking the metro to Belleville to wander around there and Ménilmontant, going further south into the 20e, where we stopped for a rest in the café opposite the town hall in Place Gambetta.

We sat inside – it was a chilly day – and I enjoyed a beer while Linda tried to warm herself up with a coffee. Then there was a surprise – as I describe back in 2008:

Suddenly we heard the sound of a brass band, and then saw out of the window an approaching procession, and I picked up my camera and rushed out, leaving Linda to guard my camera bag and half-finished beer.

“Coming across the place and going down the street towards the back of the town hall was a military band leading various dignitaries with red white and blue sashes, a couple of banners, a group of children and a small crowd of adults. It was the union française des associations de combattants, the comité d’entente des associations d’anciens combattants et victimes de guerre along with other associations of patriotic citizens commemorating the 90th anniversary of the official ceasefire (at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month) in 1918, although they were doing it a few hours later in the day.”

The commemoration in November in France is still specifically for the armistice at the end of the First World War, though there “also groups at the parade remembering the French Jews who were deported and mainly died in labour and concentration camps in the Second World War.“

Stupidly in my rush to photograph what was happening I’d left my bag with spare cards inside the cafe, and after a few frames the card in my Leica M8 was full and I had to quickly cull a few images to take new pictures. So my coverage of the event was not quite up to my normal standards.

The event had a very different feel to the Remembrance Day events in this country – such as this one I had photographed the previous year in Staines. There were a few people in uniforms in Paris, but it was very much a citizens’ event rather than being dominated by military and para-military organisations.

From the town hall it was a short walk to the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise where we took a brief stroll, but after a little late afternoon sun it began to rain more heavily and we made our way back to our hotel.

After a rest there it was time to go out find a cafe for dinner in the Latin Quarter and then to take another short walk, but it was too wet and I took few pictures.

More pictures at:

Le Paris Nord

Ceremonies du 11 novembre

Cimetiere du Pere-Lachaise

Night in the City Centre

Flickr – Facebook – My London Diary – Hull Photos – Lea Valley – Paris

London’s Industrial Heritage – London Photos

All photographs on this page are copyright © Peter Marshall.

Contact me to buy prints or licence to reproduce.