I was reminded the other day by a long thread on a private Facebook group about the controversy over taking photographs of people in public without their consent. It’s something that had a significant effect on my own practice in the 1980s before I finally came to a conclusion.

Back in 1938 and 1941, Walker Evans spent a great deal of time making a photographic study of people on the New York subway – their equivalent of London’s Underground system. He used a 35mm camera, a Contax, hidden under his overcoat with just the lens poking out and a cable release running down his sleeve to his hand to remain unnoticed by those he was photographing on seats opposite.

You can see some of the pictures he took on a page on ASX. The group at the top of the page there shows that he at least sometimes made multiple images of the same person, so he must have put a hand inside his coat to wind on between each picture. The Contax had a wind-on knob which takes a noticeable pressure to turn and its hard to see how he managed this without being obvious, but I suppose people were then completely unaware of the possibility of being photographed in this environment, and few would have identified the glass fronted object between Evan’s coat buttons as a camera lens.

Evans worked in this way to produce portraits that were entirely natural that would only rely on the individuality of the people he sat facing, a kind of raw photography where the only control he retained was over when to press the release.

Although Evans showed the pictures to friends – and got his collaborator the writer James Agee to write an introduction to them – which included the words ‘Each, also, is an individual existence, as matchless as a thumbprint or a snowflake‘ in 1940, he had reservations about publishing them about the invasion of privacy that was involved. It was only in 1966, over 25 years after they were taken, that he finally felt able to publish them in the book ‘ Many Are Called‘.

It’s clear in UK law that people have no copyright on their faces, they are not intellectual property, and that here we can generally take pictures in public of whatever we like – subject to a few specific restrictions and laws such as those governing decency and preventing stalking. But it isn’t always clear what spaces are public and which are private, and at least in theory bylaws may prohibit photography even in some that seem clearly public, including Trafalgar Square and many recent developments.

UK law makes a distinction between being in public and being where we have “a reasonable expectation of privacy“, and I think this is a very useful guide. On the open street – or on the subway or Underground – there is no such expectation, though there are still certain rules of behaviour we should observe, whether or not we are taking photographs. Generally we should not be rude or obtrusive, threatening or interfering unless there is very good reason to be so.

Apart from this, if we take and publish photographs – with or without consent – I think we have a responsibility towards those we photograph not to misrepresent them or treat them in a derogatory manner. That doesn’t mean always making ‘nice’ photographs, and if people are behaving badly there is nothing wrong with pictures that make that clear.

So, do I ask for consent when taking pictures? Occasionally but only very occasionally. Generally it seems less of an intrusion not to do so. Most of the pictures I take are of people involved in events where there is at least an implied permission and often an actual desire to be photographed. If you are taking part in a protest you are making a public statement and wish that to be recorded and publicised – and should there be some particular reason for your face not to appear, then you can always wear a mask – something Covid has made even more acceptable.

So when do I ask, either verbally or by gesture? Mainly when I want to invade someone’s personal space, going in close for an image, just very occasionally when I want them to do something. I never actually pose people but occasionally may ask them to face in a particular direction or hold a placard higher – or turn it the correct way up.

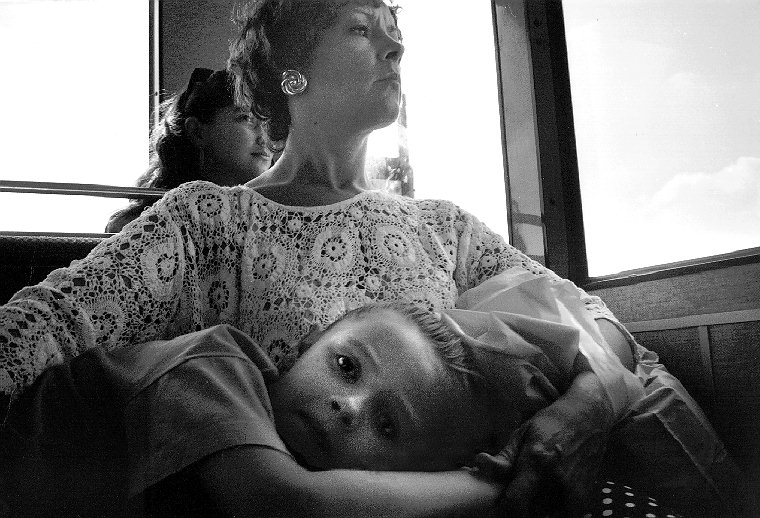

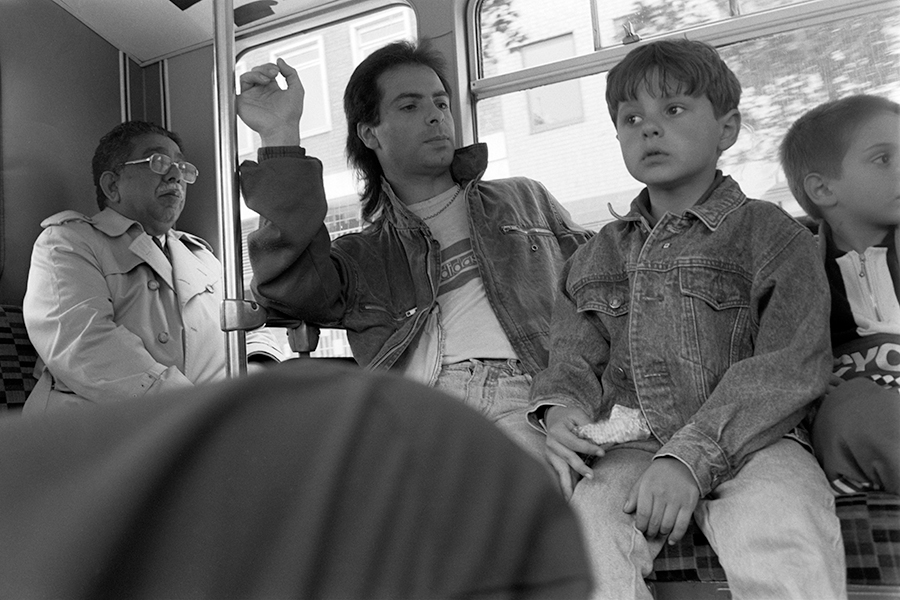

I had to sort out my views on consent clearly around 1990, when I took part in a project on transport in London which was exhibited at the Museum of London. I had two sets of pictures in the show, one of which showed the building of the DLR extension to B which involved no such problems, though perhaps a little trespassing to get the viewpoints I wanted.

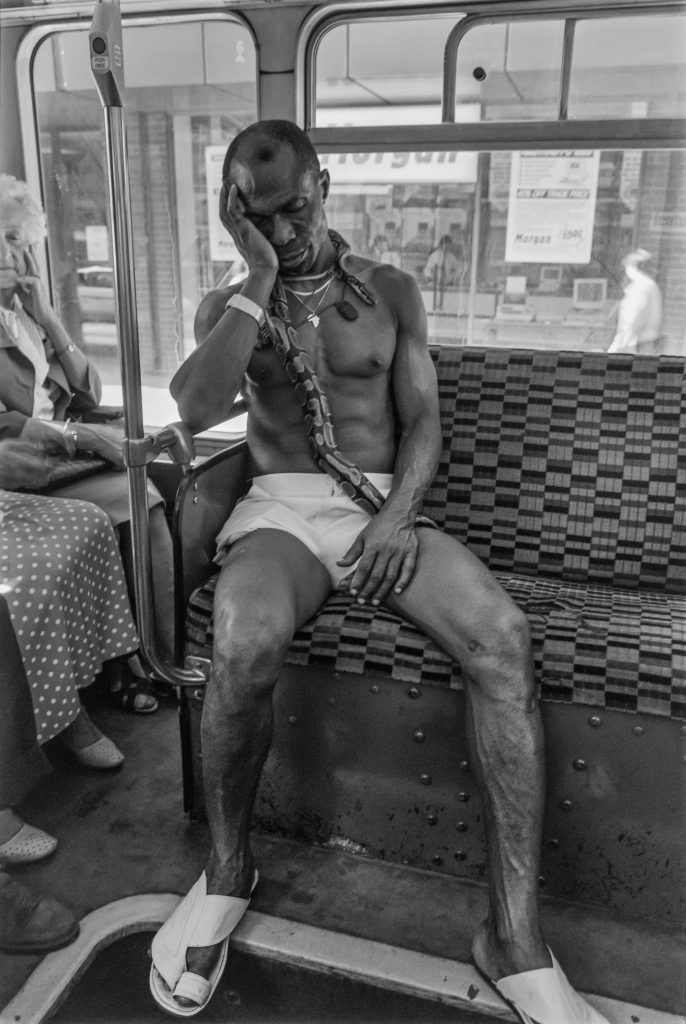

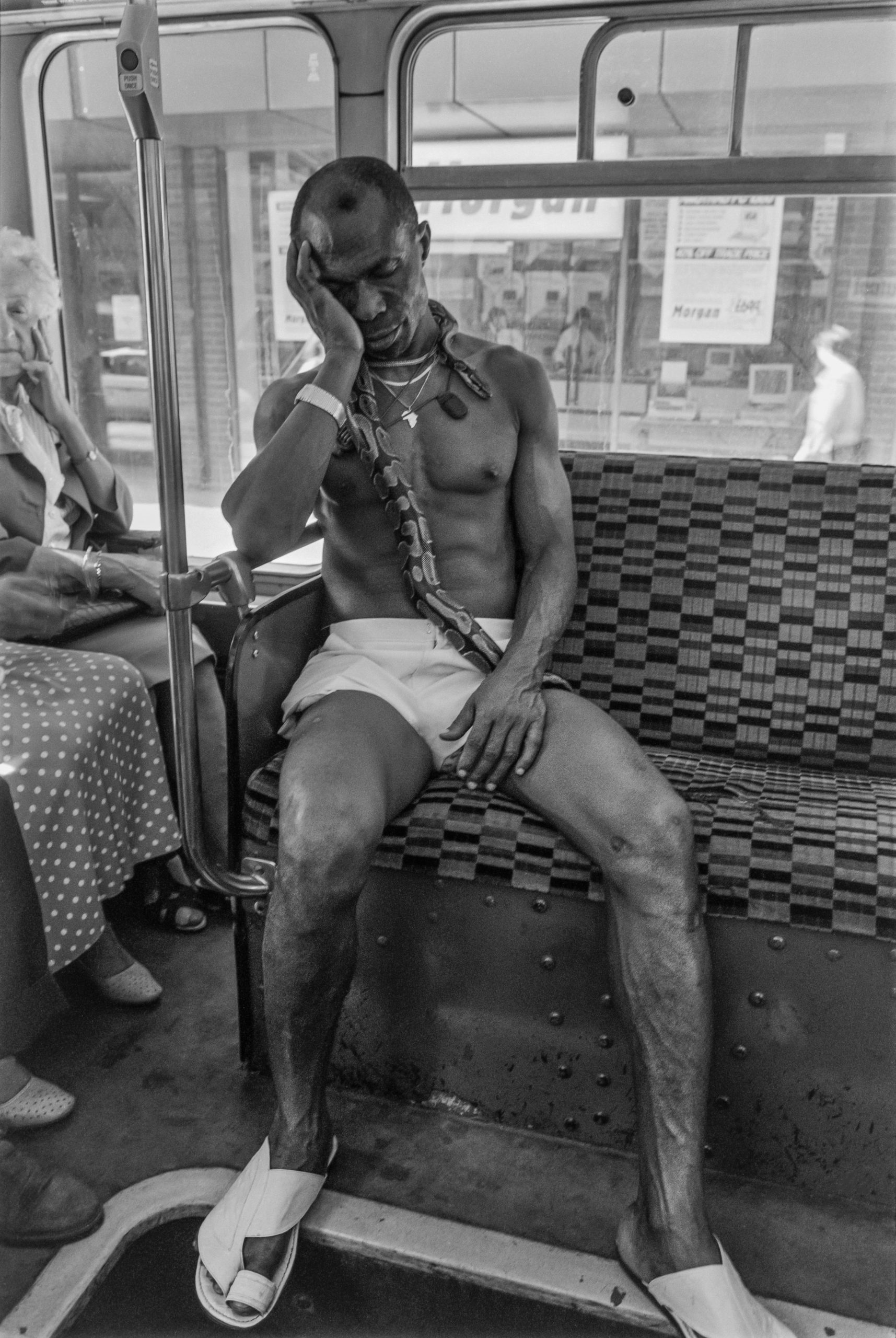

But for a second set I decided to photograph people on buses, which very much did. There seemed to be no way I could make any kind of pictures I wanted by always asking for permission. I decided to make pictures, not quite like Walker Evans, but without seeking consent, sometimes holding the camera away from my eye when taking pictures, partly to get a more interesting viewpoint. A few people did see me taking pictures but only one objected – the man wearing a snake.

It’s perhaps time now, over 30 years after taking these pictures that I made a book of them.