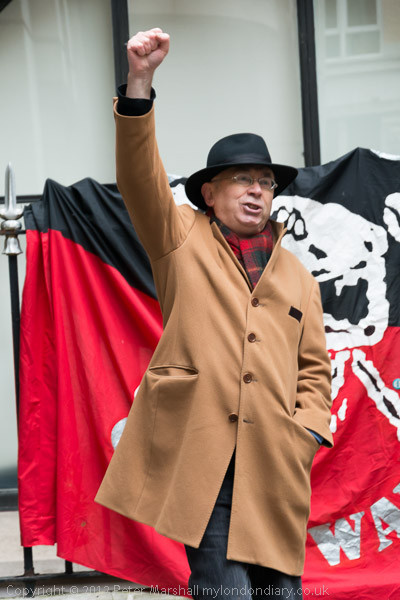

Stop The War March: Although I’ve usually posted events from the past on the actual anniversary, this post comes a day late as by the time I remembered this I had already written a post for yesterday. So although I’m publishing this on 19th November, the march organised by Stop The War took place on November 18th 2001. It was a large one, although as I wrote the reports by police severely under-counted the numbers taking part.

The Stop the War Coalition had been founded in September 2001 in the weeks following 9/11 after George W. Bush had announced the “war on terror”. At first its protests were mainly directed against the war in Afghanistan, but later it opposed the the US-led military invasion of Iraq and since then has campaigned against other wars against Libya, in Syria and elsewhere.

In recent years it has been one of the groups involved in the many protests, small and large against the genocide taking place in Gaza along with CND and the Palestine Solidarity Campaign.

I had covered their first major march by Stop the War in October 2001 and have continue to photograph many of their events to the present day, though for medical reasons had to miss the largest public demonstration in British history on 15th February 2003 shortly before the invasion of Iraq on 20 March 2003.

Back in 2003 the coalition was a huge one. Wikipedia states “Greenpeace, the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party (SNP) were among the 450 organisations which had affiliated to the coalition, and the coalition’s website listed 321 peace groups.”

The Socialist Workers Party has always played a leading role in Stop the War and the Muslim community has been important from the start with the coalition recognising “a war against Afghanistan would be perceived as an attack on Islam and that Muslims, or those perceived as being Muslim, would face racist attacks in the United Kingdom if the government joined the war.” The Muslim Association of Britain was closely involve in organising this and other protests.

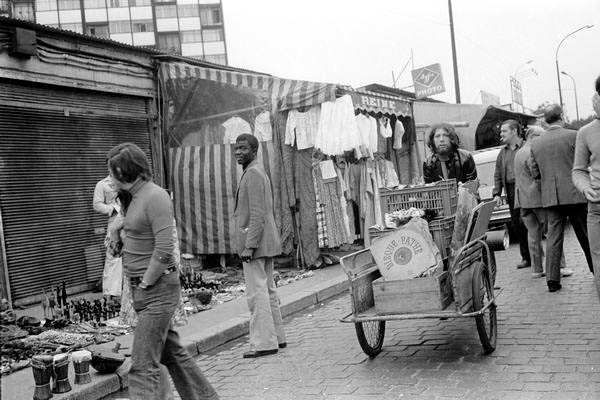

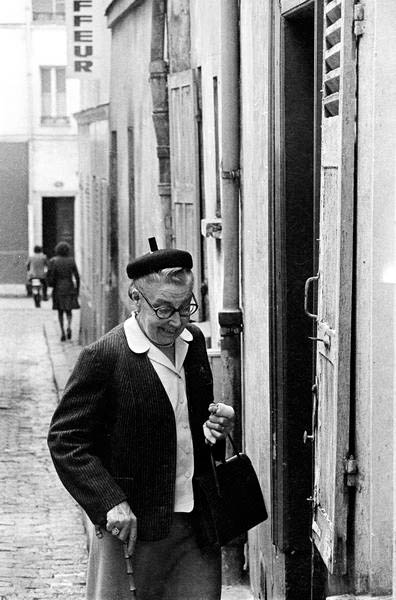

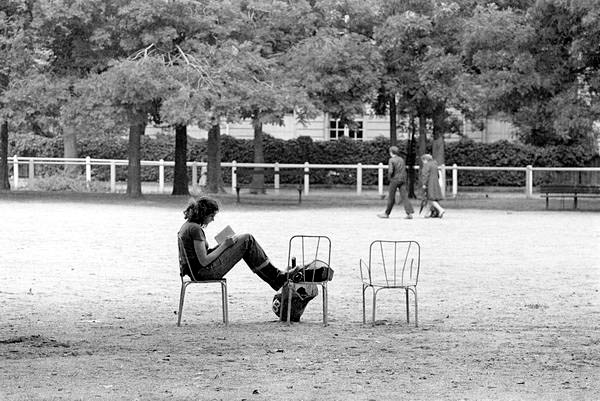

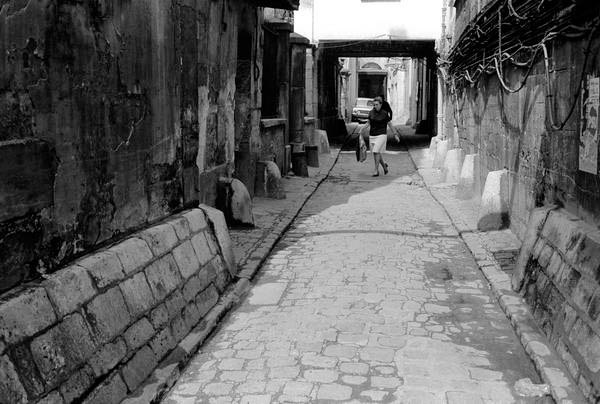

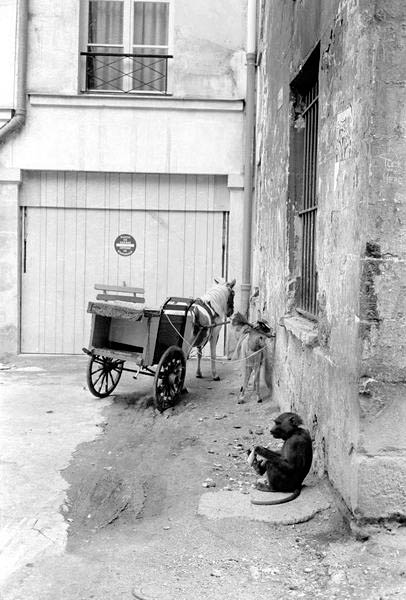

In 2001 I was still photographing using film, both black and white and colour, and all of the pictures I contributed to picture libraries were in black and white, as are those on My London Diary. Back then the demand from newspapers and magazines was still mainly for black and white and was still reproduced largely from prints.

Occasionally I would print images taken on colour negative as black and white prints to submit but mainly I had sufficient pictures taken as black and white. There are some people who now convert their colour digital images into black and white, feeling I think that it somehow makes them more ‘authentic’. It does occasionally make images stronger but mostly it simply makes them less descriptive and often confused.

Below is the post I wrote for My London Diary. It says nothing about why the protest was taking place, which would have been obvious to viewers at the time that it was against the war in Afghanistan.

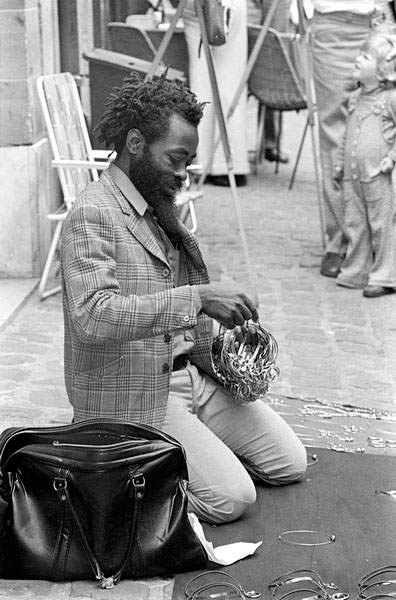

“November 18 we were back again marching to stop the war. Two hours after the march started there were still marchers leaving Hyde Park, and we were getting messages that Trafalgar Square was full. The police estimate of 20,000 was pathetically low and even the organisers’ figure of 50,000 might have been on the low side. It’s always difficult to count such things (I usually give up counting around the one thousand mark when I’m covering demonstrations and make a guess above that, but this was certainly on a similar scale to the countryside march which is the largest event in recent years.

The march was more split up into factions than most, although the start was fairly mixed. There were large organised male and female sections of Muslims for Justice in the middle of the march and a big group of younger marchers, including anarchists, towards the end. Actually I didn’t manage to see the end of the march, and people were still arriving in Trafalgar Square when I left.”

A few more pictures on My London Diary

Flickr – Facebook – My London Diary – Hull Photos – Lea Valley – Paris

London’s Industrial Heritage – London Photos

All photographs on this page are copyright © Peter Marshall.

Contact me to buy prints or licence to reproduce.