Freedom to Film & World March for Peace: On Sunday 18th October 2009 I went to Dalston to support a Hackney education charity whose students have been harassed when making films in public places and then joined a small march in the UK which was part of a worldwide humanist movement for peace.

Ridley Road Market: Worldbytes Defends Right to Film

Worldwrite is a Hackney-based education charity founded in 1994 which gives young people free film and media training supporting them to produce alternative programmes for broadcast on WORLDbytes, the charity’s online alternative Citizen TV channel Worldbytes.org. You can read more about them on the web site where you can also see a very wide range of their videos, though I couldn’t find anything now on this 2009 event.

In 2009 their teams were “finding it increasingly difficult to film in public places in Hackney: security guards, community wardens and self-appointed ‘jobsworths’ are refusing us ‘permission’ to film on many of our streets.”

As they stated, “There is in fact NO LAW against filming or taking photographs in public places and permission or a licence is NOT required for gathering news for news programmes in public spaces.“

They had called for photographers and film-makers to go along and take pictures in support of their protest and I went to do so at Ridley Road Market in Dalston, where Worldbytes crews had been told they can’t film there, not by the stall holders or other market users, but by employees of Hackney Council.

I went there to support them and the right to photograph in public places, but also because I wanted to photograph the market. I had previously taken a few pictures there but only as I was passing and had not seriously photographed the market.

After talking to the Worldwite protesters I set about walking up and down the market taking photographs of the buildings and people, particularly some of the stallholders. As well as my post on My London Diary, I wrote about the event at greater length here on >Re:PHOTO a few days later. Here’s a short section of text from that article:

“I took some general views without asking anyone for permission, but as usual, where I wanted to take pictures including stallholders or other people I asked if I might. Not because I need to, but out of politeness, and I shrugged my shoulders and moved on if they refused. Of course at times I photograph people who don’t want to be photographed, but this wasn’t appropriate here.”

“As I was using flash most of the time, it was clear that I was taking pictures and some people asked me to photograph them who I might otherwise have walked by. At one place I did stop to argue after having been refused – and eventually managed to get permission to take a picture; at another I got profuse apologies from an employee who was obviously sorry that the stall owner had decided not to cooperate with Worldbytes.“

“The council employees didn’t turn up to stop filming while I was there; probably Sunday is their day off. But it’s very hard to understand why Hackney Council should allow or instruct their employees in this way. They should know the law after all.”

My use of flash – generally as a fairly weak fill-in – was deliberate to make sure that people knew I was taking photographs, though in some cases it helped with the pictures. After I’d spent around twenty minutes obviously taking pictures I was interviewed by the Worldbytes crew, though I rather hoped they would cut that from their video of the day.

My London Diary : Ridley Rd Market: Worldbytes Film Protest

Re:PHOTO: Worldbytes Defend the Freedom to Film

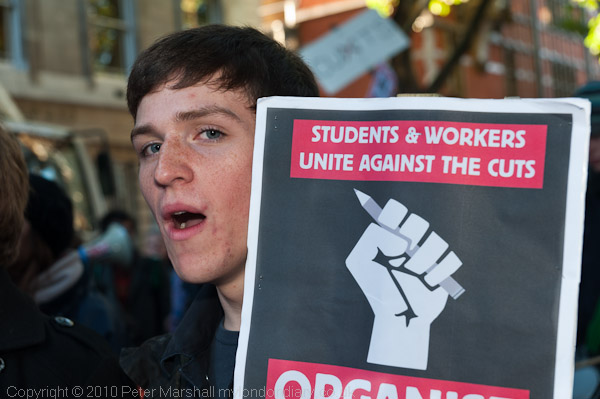

World March For Peace and Nonviolence

The World March For Peace and Nonviolence had begun in New Zealand on the 140th anniversary of Ghandi’s birth, October 2, 2009. It involved events around the world which ended at Punta de Vacas in the Andes Mountains in Argentina on January 2, 2010, where Silo (Mario Luis Rodríguez Cobos) the founder of the Humanist Movement launched a new campaign for global nuclear disarmament in September 2006.

Volunteers from a base team of around a hundred went from New Zealand to Japan, Korea, Moscow, Rome, New York, and Costa Rica, attending events organised along the way to Argentina.

In London the march began with a vigil close to the Northwood Permanent Joint Forces / NATO Headquarters in Middlesex on Saturday morning, with speeches by World March UK co-ordinator Jon Swinden, Sonia Azad of Children Against War and organiser Daniel Viesnik, who also read out a message of support from John McDonnell MP.

Only around 50 people walked the whole way, but there were others around the world also marching. On the second day in London they began at Brent Town Hall in Wembley Park and I met them as they arrived at Marble Arch. They stopped for lunch at Speaker’s Corner where they then took part in the interactive play ‘Let The Artists Die’ on themes of peace, non-violence and the power of the imagination. It was written and directed by Charlie Wiseman who was also one of the three main actors.

They walked past the front of the US Embassy to the memorial to the British victims of 9/11 in Grosvenor Square, where it stopped to pay its respects. In Mayfair it was almost halted when a taxi driver deliberately drove into one of the marchers, but they continued to Trafalgar Square.

‘Heritage wardens’ stopped the march as it came down the steps in Trafalgar Square, telling them they could not walk through the square as they had not applied for permission.

After resting for a few minutes on the steps the march went around the side of the square and down Whitehall past “the Old War Office, and then the statues of famous generals outside the “Defence Ministry” (governments were more straightforward with language in the past)” and “the fortified gates of Downing Street and on to Parliament Square, where the march stopped at the permanent peace protest by Brian Haw there since 2 June 200l with the help of his supporters.”

I left the marchers there but they continued on to end at the Peace Pagoda in Battersea Park.

More pictures at World March For Peace and Nonviolence.

Flickr – Facebook – My London Diary – Hull Photos – Lea Valley – Paris

London’s Industrial Heritage – London Photos

All photographs on this page are copyright © Peter Marshall.

Contact me to buy prints or licence to reproduce.