Life or at least writing this blog was rather easier in those pre-Covid days. Then I was still getting out and visiting places and covering events, meeting people and going to exhibitions, and there was usually something obvious for me to write about. Now I’m largely living in front of a screen, simply taking the occasional walk or bike ride for exercise and watching and listening aghast as Britain slides increasingly into a country ruled by greed and moving into fascism. Certainly dispiriting times.

So I’ve been looking back, publishing on Flickr the work I made back in the 70s and 80s (and soon the 90s) much of which has never been seen before, and also in writing in posts like this about things that I covered on this day a two, three or twenty years ago. And that’s a problem too. Today I had the choice between 2008, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 or 2018 (and possibly more) in all of which I was taking pictures of events on London’s streets on March 21st. Should I go for racism, anti-racism, tax-dodging and fair treatment for low paid workers in 2015 or against deportations, knife crime and Lambeth Council closing community centres in 2017? Should I choose on issues or on my opinions of how good my pictures were?

In the end I chose 2008 for today, largely because its different to most of the other days I’ve written about recently. It perhaps is time for a short rest from me banging on about corrupt Labour councils, though in the 2017 piece I wrote on closing community centres there I did have a nice quote from Anna Minton who found that “20 per cent of Southwark’s 63 councillors work as lobbyists” for developers in the planning industry and that a significant number of Councillors and Council officers are making use of a ‘well-oiled revolving door’ to the industry.

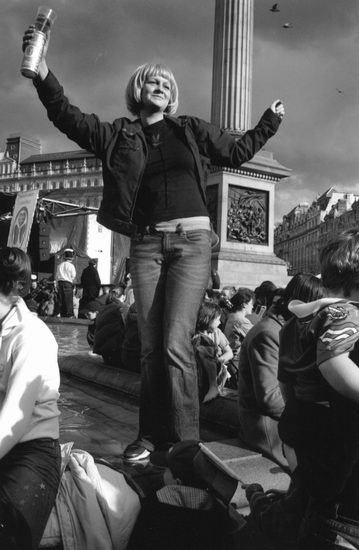

But March 21st 2008 was for me a day about religion in London, with three religious festivals coming together, Christians celebrating Good Friday, the Jewish festival of Purim and Hare Krishna celebrating Gaura Purnima. Although these happen around the same time of the year they seldom all fall on the same day. For 2021, Gaura Purnima is on the 28th March, Purim was on 25-6 February and Good Friday comes on April 2nd.

Back in 2008 I also covered other religious festivals in London, ncluding the Druids featured yesterday, and at the end of March Vaisakhi in Hounslow. In April I took pictures at Milad 2008 – Eid Milad-Un-Nabi, Woolwich Vaisakhi and Manor Park Nagar Kirtan.

You can find out more about these events and see many more pictures on My London Diary:

Gaura Purnima – Hare Krishna

Purim Fun Bus

Good Friday Walk of Witness