FotoArtFestival Diary 2007 – Poland: In 2007 I was invited to speak at the second FotoArtFestival in Bielsko-Biala, Poland and made a fairly lengthy illustrated diary of my visit. I’d been there two years earlier at the first festival there in 2005 and had enjoyed the event greatly, although it was not without a few problems, but it had been a great success.

I’ve been reminded of this in recent days by several things. Firstly by seeing pictures from this years FotoArtFestival on Facebook, the 10th of these remarkable events still being organised by the wonderful Inez Baturo from 13-29th October 2023.

Also on Facebook recently I’ve been seeing again and admiring many of the pictures by Misha Gordin, (1946-2020) who arrived in Krakov on the same flight with me. His conceptual images constructed in the darkroom are powerful and quite remarkable. I still can’t quite imagine how he produced some of them, though my diary says what he told me about his methods. You can read more about his pictures in a 2007 article by A D Coleman on his Photocritic International site, Misha Gordin: Reflex of Freedom.

And on a quite different Facebook group, someone recently posted an image from Bielsko-Biala that jumped off the screen. It wasn’t one that I had taken, but of one of the most famous doorways in the city that I had also photographed. I posted as a comment a picture the had taken in 2005 – the top one on this post.

I hadn’t gone there on either of my two visits to take photographs and in terms of photo gear on both occasions had travelled light, with just a pocketable digital camera, intending simply to create a diary of the event. In 2005 that was a 3.9MP Canon DIGITAL IXUS 400, but by 2007 I had upgraded to a 6.1MP Fuji FinePix F31fd. As you can see from the pictures in both my 2005 and 2007 diaries, both were pretty capable little cameras.

Bielsko-Biala is a city in southern Poland around 240 miles from Vienna which became an important centre for the textile industry in the 19th century when it was a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and became home to many wealthy industrialists. Many had homes built in styles then popular in Vienna, particularly Art Nouveau and there are some fine examples in what is often called “Little Vienna”.

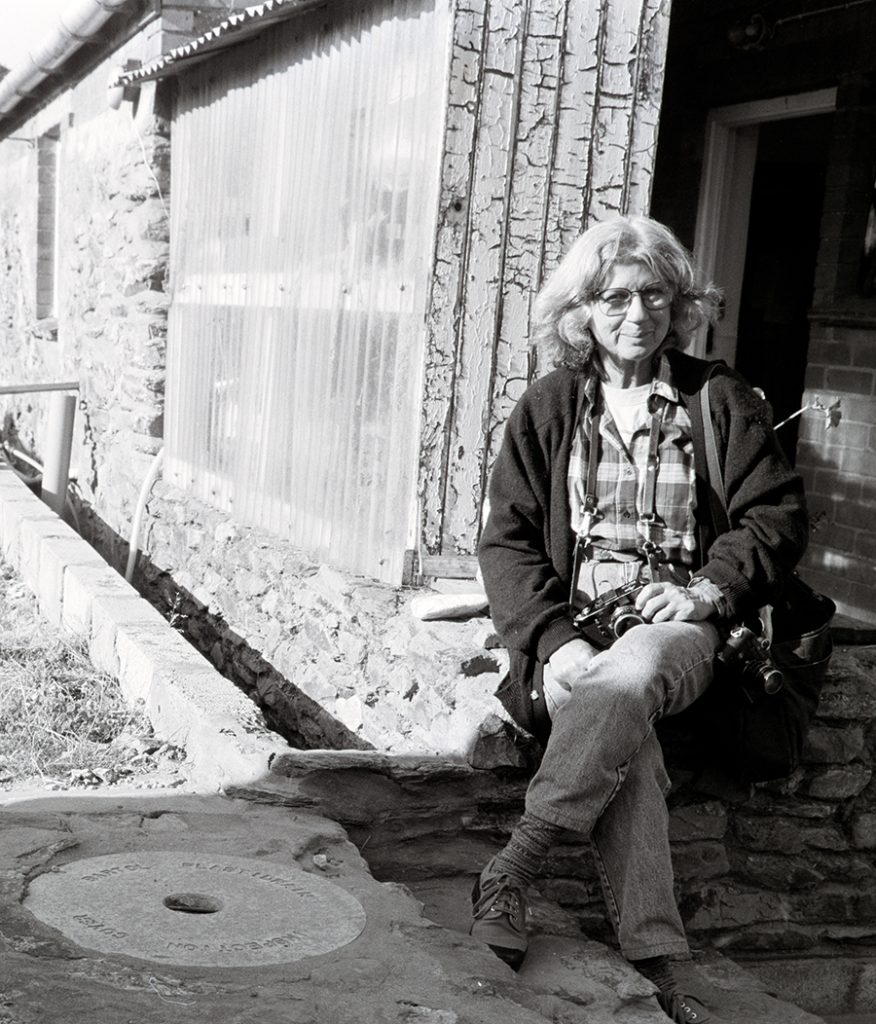

I rose early and walked around the centre of the city before the festival venues and events began taking pictures as well as walking with the others between events. My diary also has some brief reviews of some of the shows in the festival by Michal Macku (Czech Rep), Karol Kallay (Slovakia), Stasys Eidrigevicius (Lithuania/Poland), Aleksandras Macijauskas (Lithuania), Michael Kenna (UK), Walter Rosenblum (USA), Jose Luis Raota and Pedro Luis Raoto (Argentina), Franco Fontana (Italy), Judit M Horvath and Gyorgy Stalter (HUngary), Joan Fontcuberta (Spain), Misha Gordin (Latvia/USA), Lukas Maximilian Huller (Austria), Sarah Moon (France), Alex ten Napel (Holland), Mitra Tabrizian (Iran/UK) and Dalang Shao, Du Shao and Jiaye Shao(China) as well as accounts and pictures of some of the festival events. Most of those who were able to attend are in my pictures in my diary.

You can read all 16 pages of my FotoArtFestival Diary 2007 online – with many more pictures. I’ve made no real changes other than correcting the date at the top of each page. Probably many of the links in it will no longer work and those who reach the end will find will find that I still haven’t managed to put my talk from 2007 online. Copyright problems are probably insurmountable.