Housing remains a major problem, with many people and families in London still having to live in inadequate and often dangerous conditions. It isn’t that there is a shortage of homes, as many lie empty. There is a shortage, but it is of homes that people can afford to live in.

What London desperately needs is more low-cost housing. Council housing used to provide that, and by the late 1970s almost a third of UK households lived in social housing provided on a non-profit basis. Post-war building programmes, begun under Aneurin Bevan, the Labour government’s Minister for Health and Housing led to the building of estates both in major cities and the new towns that provided high quality housing at low rents, attempting to provide homes for both the working classes and a wider community.

Successive Conservative governments narrowed the scope of public housing provision towards only providing housing for those on low income, particularly those cleared from the city slums, reducing the quality of provision and also encouraging the building of more high-rise blocks, something also favoured by new construction methods of system building. Housing became a political battle of numbers, never mind the quality.

It was of course the “right to buy” brought in under Mrs Thatcher that was a real death blow for social housing. As well as losing many of their better properties, councils were prevented from investing the cash received from the sales in new housing – and the treasury took a cut too. Tenants seemed to do well out of it, getting homes at between half and two thirds of the market price, but often having bought their homes found the costs involved were more than they could afford, particularly when repairs were needed. Many of those homes were later sold and became “buy to let” houses.

Around ten years ago I passed an uncomfortable 25 minutes of a rail journey into London when a young student with a loud public-school voice explained to two friends what a splendid scheme “buy to let” was. He was already a landlord and profiting from it. You didn’t he told them actually have to have any money, as you could borrow it against the surety of your existing property – or a guarantee from Daddy – at a reasonable rate. You then bought a house and let it out, through an agency to avoid any hassle of actually dealing with tenants. Even allowing for the agent’s fees the rents you charged would give you a return on your investment roughly twice you were paying on your loan. It was money for nothing. And so it was for those who could get banks and others to lend them money, though recent changes have made it a little less profitable.

New Labour did nothing to improve the situation, and even made things worse through encouraging local councils to carry out regeneration schemes, demolishing council estates and replacing them with a large percentage of private properties, some largely unaffordable “affordable” properties and usually a token amount of actual social housing. The situation has been was still worsened since then, both by extending the right to buy to Housing Association properties and also by changes in tenure for those still in social housing. Successive governments have also driven up both house prices and rents by various policies, particularly the subsidies for landlords provided by Housing Benefit.

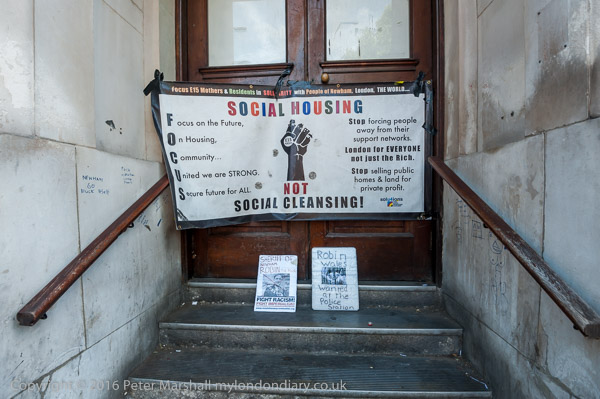

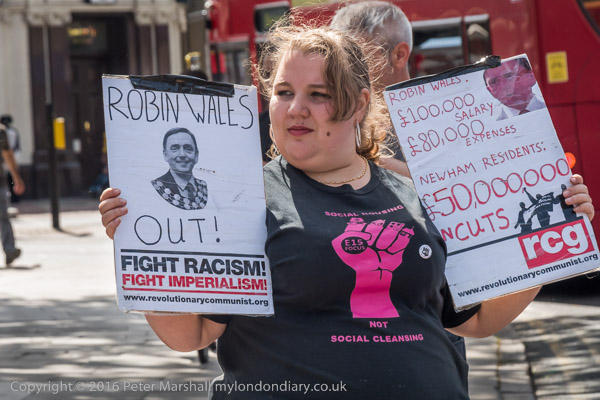

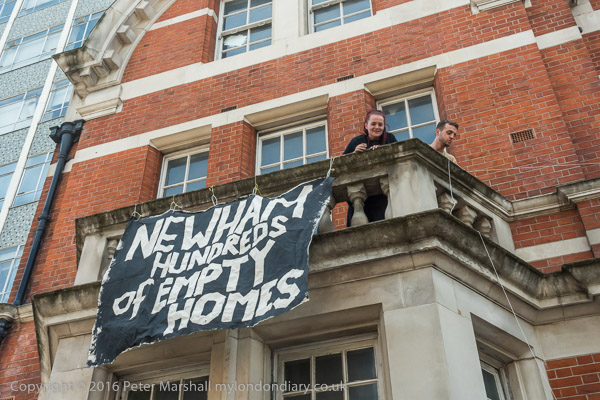

I’ve written before about Focus E15, a small group based in Newham whose activities have prompted some national debate. Begun to fight council moves to close their hostel for single mothers and disperse them to privately rented accommodation across the country (like Katie in ‘I, Daniel Blake who gets sent to Newcastle), having succeeded in their fight to stay in London they widened their scope to help others fight for decent housing – particularly in Newham, where the Labour council under Mayor Robin Wales was failing to deal with some of the worst housing problems in the country – while keeping large numbers of council properties empty.

Eventually Newham got rid of Robin Wales (and their campaign almost certainly helped) but the housing problems remain. A few days ago Focus E15 tweeted

Brimstone house in Stratford is the former FocusE15 hostel, now run by Newham Council as temporary and emergency accommodation.

One of Robin Wales’ big PR operations was the annual ‘Mayor’s Newham Show’ held in Central Park. Focus E15 were stopped from handing out leaflets inside or outside the show and on 1oth July 2016 set up a stall and protest on the main road a few hundred yards away. After handing out leaflets to people walking to the show for an hour or so, they briefly occupied the balconies of the empty former Police Station opposite Newham Town Hall on the road leading to the show ground in a protest against the Mayor’s housing record and policies.