Beekeepers Protest – and some graffiti: On Tuesday 5 Nov, 2008 I went to a protest by bee-keepers outside Parliament calling for more to be spent into research into the threats that bees were facing across the world – and which threaten our food supply. On my way back for my train I took a slightly longer route through Leake Street, the graffiti tunnel under the lines into Waterloo Station. I wrote a more personal than usual piece related to the bees back in 2008, and here I’ll post a corrected and slightly enlarged version of this with a few of the pictures.

Beekeepers Protest – Spend More on Research

Old Palace Yard, Westminster

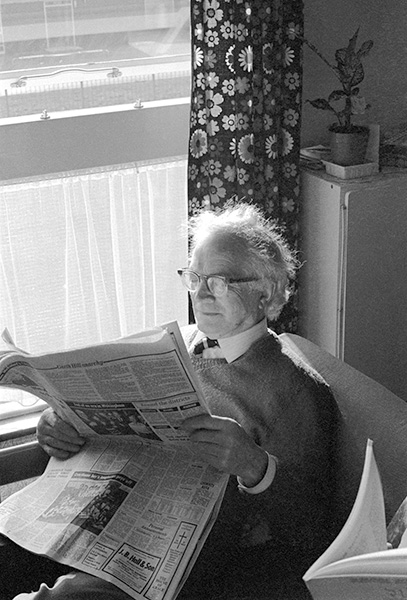

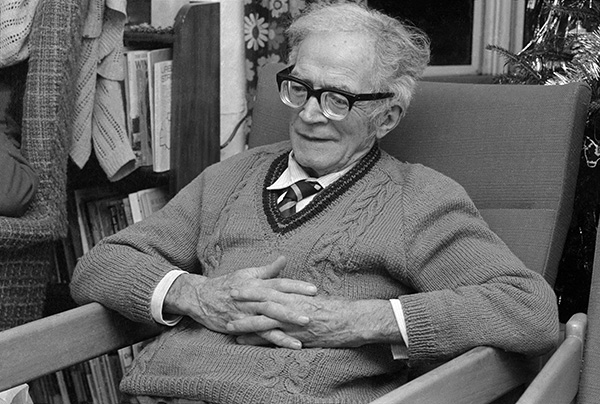

Forget the birds, it was the bees that led to my existence. My father, then a young bachelor, signed up for a bee-keeping course at the newly founded Twickenham and Thames Valley Bee-Keepers Association and made friends with his similarly aged instructor. Both had younger sisters, and soon, thanks undoubtedly to the magical properties of honey, there were two engaged pairs – and, in the fullness of time, me. Though that was rather later as I was my parent’s fourth and final child.

Both Dad and Uncle Alf kept bees for money as well as honey, both gained certificates at various local and national honey shows. For Dad it was only one of the many small jobs as carpenter, plasterer, plumber, roofer, bricky, glazier, electrician, painter and decorator, gardener and more by which he scraped a living, but I think for Alf it was his only job.

Dad’s second war service involved getting on his bike to inspect hives across Middlesex for foul brood, and for a time he was paid to look after the T&TVBKA’s own bees at their apiary in Twickenham, as well as those of Mr Miller at Angelfield in Hounslow, and of course he had his own on several sites, while Uncle Alf had hives in west country orchards as well as locally.

So although I’ve never kept bees, I certainly learnt about them helping Dad as a young boy, and learnt to love honey. We used it liberally, as while for most people honey came in small glass jars, ours came in 28lb cans – and I had been the motive power to turn the handle of the extractor to spin it out of the combs.

I’d also help my dad when he went to open the hives, perhaps to add or take off a layer of combs or simply inspect them. I’d puff the smoker into which we had stuffed a roll of smouldering corrugated cardboard to pacify the workers inside and buzzing around, my head in a gauze veil to keep the bees out. But often – if not usually – I’d still get at least one sting. They hurt, but my father seemed immune, simply brushing the bees off his usually bare arms. And he certainly felt bee-stings were good for you.

The police got to know Dad well and any time there was a swarm in the area there would be a knock at our front door. Dad would get on his bike with a box and his bee gear on the rear rack and cycle off to deal with it, bringing the bees back to put in an empty hive.

For Dad honey was the cure for all ills. We gargled with it in warm water when we had colds and he smeared it on his toes when he had chilblains. Though I couldn’t bear having sticky toes.

Vegans criticise us for “stealing the honey from the bees” but of course we gave then candy in return, made from the extra sugar ration – stained with dye – that we got for the purpose, housed them well and ensured that they kept alive over cold winters. They owed their existence to us – and we of course all – not just me – in part owe our existence to them.

Bees aren’t just about honey, they are vital for pollination of crops, with around a third of what we eat depending on their work. The economic benefit from this in the UK is about ten times that from honey production at around £120-200 million a year.

But bees are under threat. Since the early 1990s, the Varroa mite has devastated many wild bee colonies. Bee-keepers have managed to control the mite, but now strains have developed which resist the treatments. A fungus, Nosema ceranae has added to the problems.

An even greater threat is colony collapse, a poorly understood disorder probably caused by a combination of factors including viruses, stress, pesticides, bad weather and various diseases. There have been huge loses of bees in the USA and parts of Europe but as yet is has not reached here.

Around 300 bee-keepers, organised by the British Bee-Keepers Association (BBKA) came to lobby parliament for greater research to combat the threats to bees and to deliver a petition with with over 140,000 signatures for increased funding for research into bee health to Downing St.

Most wore bee-keeping suits and hats with veils and some brought the bee-smokers that are used to calm the hives. Labour MP for Norwich North , Dr Ian Gibson, spoke briefly at the start of the protest. One of the few MPs with a scientific background, he was Dean of Biology at the University of East Anglia before being elected as an MP in 1997. The current president of the BBKA, Tim Lovett, who led the protesters, was a former student of his.

Every year the Animal and Plant Health Agency’s (APHA) National Bee Unit launches a Hive Count and the 2025 Hive count began on 1st November. Last year there were 252,647 over-wintering bee colonies in the UK and we seem so far to have avoided the catastrophic loss in bee numbers that seemed likely in 2008, though I think other pollinating insects – which are not protected by keepers – have declined.

More pictures on My London Diary at Beekeepers protest.

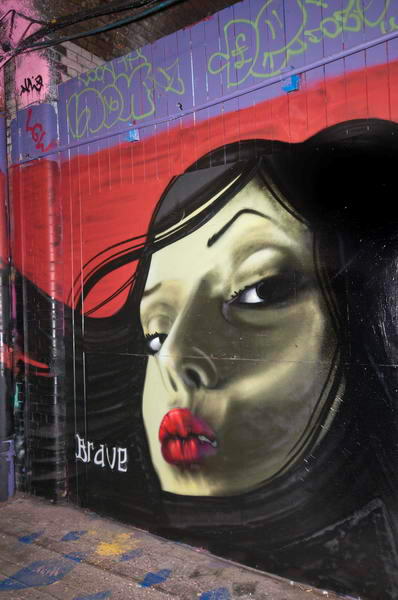

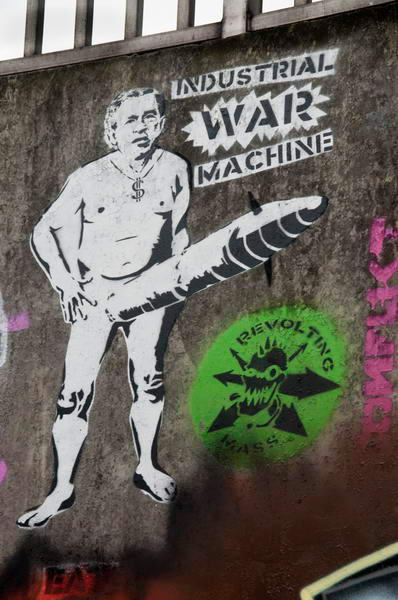

Leake St Grafitti

Leake St, Waterloo

The graffiti in my pictures from 2008 seem rather less impressive than those I’ve photographed in this official graffiti space in more recent years.

There are a few more on My London Dairy at Leake St Grafitti

Flickr – Facebook – My London Diary – Hull Photos – Lea Valley – Paris

London’s Industrial Heritage – London Photos

All photographs on this page are copyright © Peter Marshall.

Contact me to buy prints or licence to reproduce.