Late yesterday I got back from a week in Paris, and one of the highlights of any trip there for a photographer has to be a visit to the Maison Europeene de la Photographie (MEP) .

I’ll write in more detail about some of the things I saw there in other posts, but what really struck me – yet again – was the complete difference in outlook between the MEP and our London flagship The Photographers’ Gallery (PG).

Of course we can hope that some things may change when the PG moves to more extensive premises shortly, but the biggest difference so far as photography is concerned is one of attitude. The MEP clearly believes in photography, celebrates it and promotes it, while for many years the PG has seemed rather ashamed of it, with a programme that has seemed to be clearly aimed at attempting to legitimise it as a genuine – if rather minor – aspect of art. (It was something that worried photographers in the nineteenth century – but most of us have got over it by now.)

One important difference between the two spaces is that at the MEP you pay to see photography – 6 euros (3 for reductions) though Wednesday is something of a photographers’ evening as entry is then free to all. (A press card gets you in free at all times.) This charge doesn’t appear to put people off, and almost every time I’ve visited over the years I’ve had to queue anything from 5 to 20 minutes to get in. But it does make it a little more of an event to go there, and it does mean that the MEP has got to offer something people feel is worth paying for.

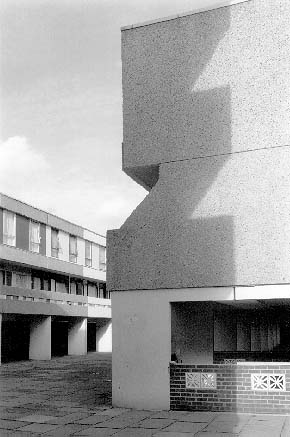

The staircase at the MEP

Of course the MEP does have a rather grand space with perhaps 3-5 times the size of the old PG, it also makes better use of it – at the PG half the space was usually largely wasted by being a coffee bar with a few pictures around the wall (and I think some other areas, such as the print room could also have been far better used.) And although I did sometimes enjoy meeting people in the cafe and having a coffee, I’d rather have been able to see a proper show and then pop across to the Porcupine or elsewhere to socialise (which of course I also did over the years.)

Sabine Weiss talks to visitors and signs books at her MEP exhibition

This time, one floor of the MEP – perhaps around the total amount of exhibition space at the PG – was given over to a retrospective of the work of Sabine Weiss – which I’ll write about in another post. A Swiss-born photographer, she started her distinguished career in Paris and took arguably her best pictures there, so this was a particularly appropriate venue, although it would be nice to see this work in London too.

But one could also propose shows by a number of British photographers of similar stature who have so far been largely or entirely neglected by the PG. Not that I would want any gallery to be insular, but I feel major galleries do have a responsibility to promote work connected to their country and place, especially when like London and Paris they have played vital roles in the history of the medium.

Another floor of the MEP showed the complete photographic works of David McDermott and Peter McGough, two USAmerican artists who have made extensive use of various alternative printing processes (good salt prints, rather indifferent cyanotype and gum bichromates etc) as a part of an extensive lived re-enaction of life as late nineteenth and early twentieth century gentlemen. I don’t think they would want to be called photographers, but their work, as well as the interest of the processes concerned was witty and full of ideas, whereas some of the shows by artists at the PG seem very much one-trick ponies – including the last that filled the space adjoining the book shop.

Another, smaller space at the MEP covered the career of Turkish photographer Göksin Sipahioglu, who became ‘Monsieur SIPA, Photographe‘ after founding his agency when he came to Paris as a photographer in the 1960s.

Sipahioglu is a perhaps unfairly often thought of as a no-frills photojournalist who excelled at being there and getting pictures rather than for subtlety, but the work on show made me want to rewrite the lengthy piece I wrote about his work a few years ago.

Also showing in the MEP were a series of colour portraits of artists in their studios by Marie-Paule Nègre, originally produced on a monthly basis for the Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot to accompany interviews with the artists. While the theme is well worn, the images were well done and often had a freshness and interest. Which is more than I can say for Mutations II / Moving Stills, a selection of videos made by European artists – part of the European Month of Photography – the short sequence of which I viewed had all the Warholian attraction of paint drying. However each did have its small group of apparently enthralled watchers.

Although of course curators play an important role in the exhibitions at the MEP (from a visit a year or two ago I recall an awesome show of the life of a single photograph by Kertesz) I get the feeling that photography at the MEP (and perhaps in France in general) is still very much based on the work of photographers. In the UK in the late 1970s the Arts Council made the fatal mistake of handing over the medium to curators and galleries, and we – as the PG evidences – are still suffering from it.