One of the reasons I post here about my work on My London Diary earlier in the year is to check up on that web site. In some ways its a rather primitive site, a throw-back to the early days of the web, entirely hand-coded, though usually with the aid of an ancient version of the best WYSIWYG software, though now that outdated description ‘What You See Is What You Get’ no longer really applies, and what I see when I’m writing the pages is very different to the web view.

I first designed the site back in 2001, and even then it was somewhat archaic, reflecting my views on simple web design at at time when flash bang and wallop was infecting the web, largely running on our relatively slow connections that weren’t ready for it. Designing image-loaded sites like this that were reasonably responsive was something of a challenge, and needed relatively small images carefully optimised for size, with just a small number on each page.

Although the site still has the same basic logical structure, times and the site have changed a little to reflect the much higher bandwidth most of us now enjoy, with several re-designs and many more images per page, as well as slightly larger and less compressed images. Size is now more a problem of controlling use (or abuse) of images than download time, and new images are now always watermarked, if fairly discretely. The latest small changes in design have been to make the pages ‘mobile friendly’ without essentially changing their look.

I suspect that My London Diary is one of the largest hand-coded sites on the web – with over 150,000 images on over 10,000 web pages. But the simple site design means the great majority of the time involved in putting new work online isn’t actually the web stuff, but editing the images and writing the text and captions, so there is little incentive for me to move away from hand-coding.

But I’m not really a writer of web sites (though I have quite a few as well as My London Diary) or this blog but a photographer and though My London Diary is important in spreading my work and ideas, it has to fit in with that. Often the web site gets written late at night or when I have a little time to spare before rushing to catch a train, and often I have to stop in the middle of things to run to the station – or fall asleep at the keyboard. So while in theory I check everything, correct my spelling and typos, make sure all the links are correct and so on, there are always mistakes. And just occasionally my ISP has something of a hiccough and puts back an earlier version of a page or loses or corrupts an image (though they deny it.)

This morning I opened the pages on End homophobic bullying at LSE , the first protest I covered after returning from Hull, only to find I’d not put any captions on them, not even adding the spaces between pictures for them to go in. So before I started to write about them I had work to do.

Otherwise I might have had more to say about the pictures. Yet again how useful the fisheye can sometimes be, or about reflections in pictures or to fulminate against homophobia, the failure of LSE management to live up to the pricinciples the instituion espouses, the inherently evil nature of out-sourcing and the need to treat everyone with dignity and respect and to pay a proper living wage. But today you can relax and take that as read.

The pictures are workmanlike, they serve a purpose, do the job, but it wasn’t one of my better days. Dull weather perhaps didn’t help, but sometimes the magic just doesn’t happen. The following day was perhaps a little better (I’ll let you decide) and certainly much busier, with pictures from five events.

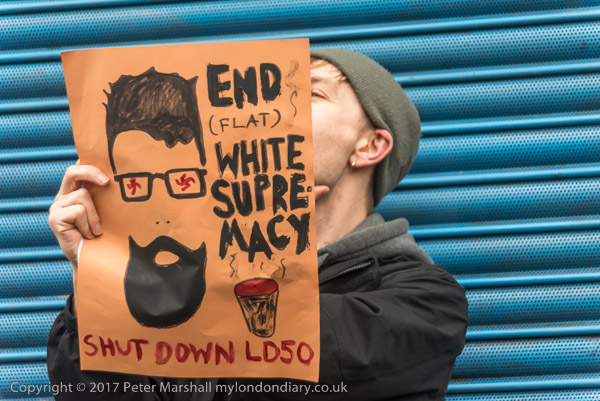

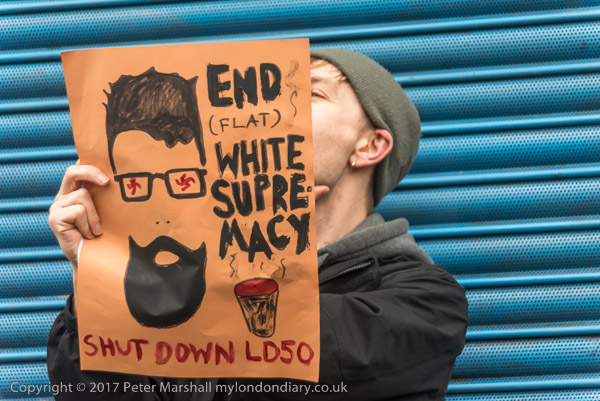

I started with Shut race-hate LD50 gallery, a crowd outside the place which they say “has been responsible for one of the most extensive neo-Nazi cultural programmes to appear in London in the last decade” , but didn’t really offer a great deal to photograph. The gallery itself was on the first floor above a shuttered shopfront, and had clearly had a brick through a window, and there were a couple of arguments outside, but mainly it was scattered people standing in small groups on the street.

Trying to do too much, I arrived late and left early for the Picturehouse recognition & living wage protest in front of the Leicester Square Empire. There’s a pleasant symmetry in the picture above, but I missed the scrum later when Jeremy Corbyn arrived to give his support.

It’s always difficult to know when to leave (or arrive) at events, and photographers spend many hours standing around waiting. But I’m impatient by nature and sometimes miss things. Other times I find a place to sit and read a book, and if its a decent book have been known to miss the action.

But I was in Brixton, meeting Beti, a victim of gentrification and social cleansing, not in her case by one of the mainly Labour London councils but the Guiness Trust, formed by a great-grandson of the brewery founder in 1890 to provide affordable housing and care for the homeless of London and Dublin and now as The Guinness Partnership owning 65,000 homes in England.

Betiel Mahari lived in one of these with her family on the Loughborough Park Estate in Brixton for ten years, paying a ‘social ‘ rent but was never given a secure tenancy. Guiness demolished her flat in 2015, giving her a new flat a few miles away in Kennington – but at a hugely increased ‘affordable’ rent, going up from £109 per week to £265. The move meant too she was unable to keep her full-time job as a restaurant manager, and is now on a zero-hours contract as a waitress and facing eviction as she cannot pay the increased rent. DWP incompetence meant that her benefits were suspended completely for three months (and on zero hours contracts the benefits have to be re-assessed every three months in any case) and Guiness were taking her to court over rent arrears.

The case was heard around 10 days later and as thrown out by the judge who ordered the Guiness Partnership to pay Beti’s court costs, but the struggle to get this rapacious ‘social’ Landlord to treat her and others in similar straits continues. I was pleased to be able to support her, though not entirely happy with the pictures at Stop Unfair Eviction by Guinness, which also include some of Brixton Arches.

I arrived back in Westminster just in time to meet the Khojaly marchers coming down Whitehall to end their protest in front of Parliament. Few of us will remember the massacre on the night of 25-26 February 1992 when Armenian forces brutally killed 613 civilians in the town of Khojaly, including 106 women and 83 children, but the name Nagorno-Karabakh may prompt some memories. In 25th anniversary of Khojaly Massacre I try to give a little background to the still unresolved situation.

But I was on my way to an event marking the shameful failure of Theresa May and her government to take the action demanded by Parliament to bring the great majority of the refugee children stranded at Calais and similar camps into this country. By passing the Dubs Amendment, Parliament made its view clear and it reflects a failure of our constitution that there seems to be no legal mechanism to force the Tory government to carry this out. This is truly a stain on our country’s history and May and her cabinet deserve to be behind bars for this crime against humanity.

Dubs Now – let the children in

Continue reading Business as Usual