Partition of India back in 1947 was a bloody business, and one that continues to have many bloody repercussions, not least in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, which was the subject of an earlier show curated by Shahidul Alam (with Mark Sealey) ‘Bangladesh 1971‘ at Autograph ABP in Shoreditch, London, in 2008.

Although the great majority of the population of Bangladesh are Bengali, some areas of the country have considerable numbers of indigenous peoples, notably in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) in the south-east, bordering Myanmar and India, where they form roughly half of the population. Collectively known as the Jumma, the largest ethnic group is the Chakma (also known as Pehari) people. Unlike the Bengali majority who are largely Muslim, the indigenous people are mainly Buddhists.

Lord Mountbatten, sent as Viceroy to India to oversee independence and partition, was so concerned over the Boundary commission’s decision to include the CHT in East Pakistan that he delayed announcing the commission’s decisions until the day after Independence Day as he feared it would provoke a powerful reaction, with boycotts of the celebrations.

After independence the Bangladeshi government have attempted to solve the problem by settling the area with Bengali people, and the hill tribes set up a resistance movement with a guerilla force (encouraged covertly by India) which launched an insurgency in 1977 and the area became highly militarised, with government forces and paramilitary groups carrying out atrocities including mass rapes, genocide and ethnic cleansing.

Although a peace treaty was signed in 1997, Wikipedia reports “According to Amnesty International as of June 2013 the Bangladeshi government had still not honored the terms of the peace accord nor addressed the Jumma peoples concerns over the return of their land. Amnesty estimate that there are currently 90,000 internally displaced Jumma families.”

Kalpana Chakma “was a vocal and charismatic leader who campaigned for the rights of the indigenous people” of which she was one, and had become leader of the Hill Women’s Federation, speaking out against the military occupation and handing out their land to Bengali settlers. She was only 23 on 12 June 1996 when, a few hours before voting began in a national election in which she had been campaigning for an independent candidate, Lieutenant Ferdous and other members of the Bangladesh Army raided her family home and abducted her and her two brothers.

Attempts to report her abduction and get information from the army and police were refused, and continuing attempts to get at the truth about what happened to Kalpana Chakma have been met with deliberate lies and obfuscation.

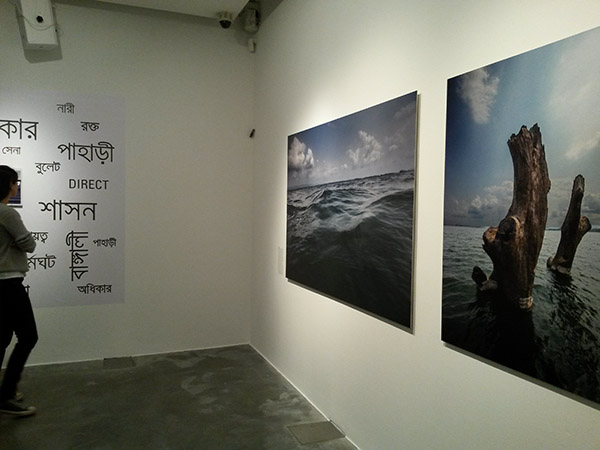

Shahidul’s work in ‘Kalpana’s Warriors‘, curated by him together with Rahnuma Ahmed, Saydia Gulrukh, Dadia Marium and ASM Rezaur Rahman is an attempt to ‘break the silence surrounding her disappearance‘ but is also a powerful celebration of her continuing influence on political activists, the ‘warriors’ who have fought to demand the truth about her abduction and to obtain justice, as well as a candlelit vigil in her memory.

It’s probably best to visit part two of the exhibition first, which contextualises the work with images which show something of the area and the movement of which Kalpana was a part. A film made by Alam shows a number of people talking about Kalpana and her influence, with English subtitles, and at 35 minutes it seems a little slow-moving.But this is a general problem with subtitled interviews in that you can read in a second what perhaps takes 15 seconds to say, and then have to wait impatiently for the next sentence.

The installation in the ground floor main gallery is impressive, with large images, heads and shoulders at much greater than life-size etched on straw mats, each illuminated by a single hanging candle. It was getting dark outside when I walked around it, and it might be just lose a little during daylight hours with more light leaking in from outside.

The straw mats are like those found in the village homes in CHT, and on one of which which Kalpana would have been sleeping when the soldiers came to take her, and the technique used to print on them also reflects the realities of life for her and her people. Before her abduction she had been leading protests against the burning of Pahari villages, and the images are burnt onto the mats using a laser beam. There are smaller 4×3″ more conventional prints in small piles against the wall around the installation which you can pick up and take away, with short texts on the reverse naming and describing the ‘warriors’.

The installation with its hanging mats in a circle which you can walk around both outside and inside is an experience with a highly religious feel to it, like entering a temple. Even on the opening night when it was relatively crowded – with numbers strictly limited to 30 inside the installation for health and safety reasons and many were using their phones to take photographs – it had a powerful atmosphere, and I think this would be more so on a normal day when it was quiet and empty.

It’s a show I recommend highly, and Kalpana’s Warriors continues at Autograph until 18 June.

Media and copyright lawyer Rupert Grey wrote a very detailed review of Shahidul Alam’s fine book ‘My Journey as a Witness‘ which includes a great deal about him as well as some pictures. You can also see videos on Vimeo and others on YouTube. You can see more work at Alam’s web site and he posts regularly on the ShahidulNews blog.