We should as a photographic nation be celebrating today, with features in the colour supplements and photographic magazines, the 70th birthday of one of the most important figures for British photography in the second half of the last century, who happily is still going strong now. But you are unfortunately unlikely to read about it anywhere but here.

Yesterday I was privileged to attend the surprise birthday celebration for John Benton-Harris in the sports club opposite his home in Croydon, with his family and a decent smattering of photographers.

Those of us who were around in the 1960 and 70s remember the great breath of fresh ideas that came across the Atlantic and re-vitalised the medium here. Two people in particular, both separately students of Alexey Brodovitch in New York and New Haven, played a greater role than any others by coming and working here. One was British, Tony Ray-Jones, who died tragically young – only 30 – in 1972, having produced the work that was published posthumously as ‘A Day Off – An English Journal‘ in 1974. The other was an American from the South Bronx who took leave from his post as a photographer in the US Army in Italy to photograph Churchill’s funeral in 1965. While in London he met a young woman who changed his life, and as soon as he was able, moved to London and married her, continuing his photographic career here. You can see both of them in the picture above.

Two years ago at the FotoArt Festival in Bielsko-Biala, Poland, it was slightly daunting to take to the stage immediately after the notable historian and writer of ‘A World History of Photography‘, Naomi Rosenblum, particularly as the talk I was going to give had a considerable overlap with the lecture on the history of street photography she had just given.

My ‘On English Streets’ used illustrations from the work of John Thomson, Paul Martin, Sir Benjamin Stone, Margaret Monck, Bill Brandt, Martin Parr, Paul Trevor and of course John Benton-Harris, as well as some of my own pictures (I’d talked there about Tony Ray-Jones on a previous occasion or he too would have featured.) Here is my script for the part of the talk which was about John:

His vision of England certainly in the early years here – was very much based on the ideas about it he had picked up from films set in the country, particularly those made by British film studios. But his view as an outsider certainly made him more aware of the class differences here and the key ways in which they are signified and in particular the importance and readings of hats, which appear in so many of his pictures.When John met another Brodovitch graduate, Tony Ray Jones in London, and found they shared many ideas (Ray Jones had studied at Brodovitch’s class in New Haven, and they had not met in the USA.) Both had the experience of having worked in a supportive visual environment that they found almost completely lacking in word-centred Britain, where no one seemed to care about photography. It must have come as a shock to John to have moved from a New York where he knew everyone who was anyone to a London where there was no one to know, although Ray Jones would have known exactly what was in store when he returned here. Together they provided an energy, a dynamic, that catalysed others to shake up of the dusty world of British photography, particularly editors Bill Jay and Peter Turner, who took over from Jay at Creative Camera. Benton-Harris curated several influential shows with Turner, particularly American Images: Photography (1945-80) at the Barbican in 1985.

The new breeze that ran though British photography affected all of us, perhaps reaching its apogee in volumes such as Creative Camera Collection 5, which featured, as the first of three major portfolios, 27 images by Benton-Harris (as well as a well hidden set of three pictures from me.)

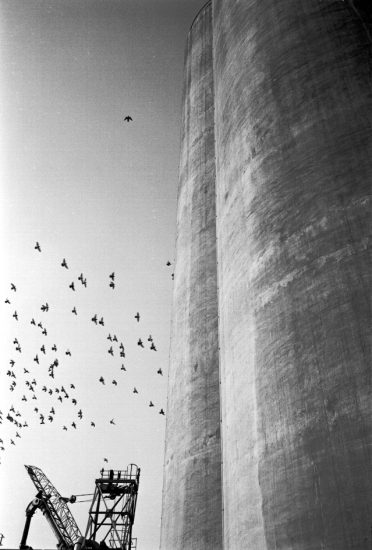

Those coming to the party had been sworn to secrecy, but were asked to nominate their favourite image by John, and these had been printed up to poster size and were stuck up around the sports hall for the party – you can see some in the background of these pictures. I’d printed out the presentation slides for his section of my talk as a small present and was pleased to see that my choice included several of other people’s favourites.

Also on display was a series of pictures of John as a young man with a camera on the streets of Rome, taken by his friend George Weitz, there at the party (I’m afraid the link to the piece I wrote on John for About.com no longer leads to it – like the several thousand other pieces I wrote for them it is no longer available on line.)

Part of the reason why John is not as highly known as he should be is that it is not easy to see his work, much only available in long out of print books and magazines. A reasonably diligent search on the web only reveals a couple of pictures of him and two poorly scanned images of St Patrick’s Day, neither his best work on the theme. We really need a well-produced book of his work from the first twenty or so years in England, as well as other publications covering his later work.

Probably the best way publication is still the major portfolio in Creative Camera Collection 5 mentioned above, still available secondhand at a very reasonable price in the USA, though more expensive here – and prices of this and the other CC Year Books do now seem to be rising fast. (My favourite on-line bookseller lists a copy at a US bookseller for £6.47 below an ‘ex-library’ copy apparently in poorer condition from a UK store for £56, though most copies are in the £16-25 range.)

But it is also unfortunate that credit wasn’t always given to him for the things that he did do. The catalogue for the ground-breaking Barbican Show American Images 1945-80 does state in the acknowldegements “Peter Turner and John Benton-Harris have been the motivating force behind the show and without their unstinting efforts as organizers, American Images would never have happened” and it carries a short note by him and about him, but essentially it marginalises his contribution to a show which was almost entirely dependent on his contribution and insights, if slightly diluted by the efforts of others.

Unforgivably he was not even included in the index to the catalogue, and the front cover which should have stated ‘Organised by John Benton-Harris & Peter Turner‘ simply says ‘Edited by Peter Turner‘.

It is also hard to understand why use wasn’t made in the catalogue of his personal knowledge of many of the photogrphers included (which was essential in putting the show together) to provide greater insight into their lives and work. As his occasional contirbutions to this site show, John is capable of writing with considerable force and insight.

John has recently returned from another extended trip to the USA, doubtless with many interesting digital colour images as on his recent previous trips. I also hope he will write up his thoughts about some of the shows that he saw there for this site. It would be nice if here or elsewhere he would also share some of his images with us.

More pictures from the party on My London Diary.