I’ve written in several previous years about the Ian Parry Scholarship award, particularly when I was writing virtually from New York but actually from Staines for About.com, not least because I wanted to remind our friends in the USA that there is photographic life outside their borders. But this is the first year that I’ve attended the awards ceremony – and the large party that accompanied it in the gallery and on the street outside.

Ian Parry was a 24 year old photojournalist shot while working for the Sunday Times covering the Romanian revolution in 1989, and family and friends set up an annual scholarship in his memory open to those attending a full-time photography course or under the age of 24.

As the exhibition at the Getty Images Gallery in Eastcastle St (near Oxford Circus) in London for the next week (so don’t delay in going to see it) shows, it attracts a high standard of work from around the world – including many from the USA.

Even more important than the prize is the prestige and exposure that the award attracts, with the exhibition and publication of work by the finalists in the Sunday Times magazine (2 Aug 2009 issue), a place on the final list of nominees for the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass and this year, an international assignment for one of the finalists from Save The Children.

The value of the award can be seen in the careers of those who have been awarded it in previous years. Last year’s winner was Vicente Jaime Villafranca and on his web site you can see some of his fine black and white work on the Gangs of BASECO.

Maisie Crow is currently working as an intern for The Boston Globe and is a graduate student in the School of Visual Communication at Ohio University. Previously she studied Spanish at the Universidad de Veritas in Costa Rica and Spanish and Art History in Seville before a BJ in Photojournalism at the University of Texas and further studies at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies, and also worked as a freelance from 2006-8.

Her winning project on Autumn, a 17 year old Ohian girl growing up in a poor and dysfunctional family environment contains some powerful and intimate images – a selection of six were in the BJP feature on the award (BJP 22/07/2009 p10). One of the captions which sets the scene reads “Autumn sits between a relative’s legs. She alleges he tried to rape her when she was 13 years old but says her parents do not believe her.”

Surprising the 12-page Sunday Times feature uses only one of her pictures, tightly cropped on the front cover. It is a highly charged scene with Autumn being attacked by her boyfriend, pushed down over the kitchen sink (the caption notes that within half an hour they had kissed and made up) printed much more harshly than the original and gaining drama at the expense of sensitivity.

Ed Ou’s Highly Commended work on the horrible deformities suffered by people living in the area of Kazakhstan where the Soviet Union carried out over 450 nuclear tests is extremely strong, and hard to view. Too much so for the Sunday Times, who use only a picture of a nurse cradling a small child; the BJP too shies away from publishing the more horrific of these powerful images from ‘Under a nuclear cloud’. Ou doesn’t dwell unduly on these aspects but they are an important part of the story, as you can see in the images on his web site (rather slow to load – but it does eventually appear.)

Some of the other work is better served in publication than on the gallery wall. The two pictures of Dennis, a sufferer from dementia and Ruby his wife, married for 61 years and now forced apart in the Sunday Times are far stronger than the sentimental portrait of the couple on the gallery wall, and made me want to see more of this project by Dan Giannopoulos.

Similarly, the two pictures by Giuseppe Moccia of an American teenager suffering from Down’s syndrome on the wall failed to grab my interest, but the Sunday Times has a far stronger image. Other photographers whose work seemed more interesting in publication included Alinka Echeverria with images of veterans of the Cuban revolution and Masud Alam Liton’s project Bangladesh: Requiem For Freedom (he has a blog – Liton Photo) and a second set of images from the same country by Mohammad Rashed Kibria.

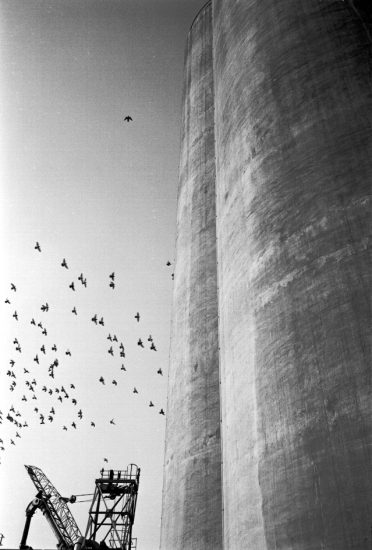

Of course the magazine page (or now the web page) is where this work really belongs, rather than the gallery wall and its perhaps not surprising that some at least works better there. The black and white work in particular seemed better suited to print than frame, perhaps reflecting the difficulties in making good black and white inkjet prints, but occasionally also the hanging. Ruben Joachim‘s Afghan child clinging to her father so intense on the printed page was lost in reflections and weaker contrast on the wall.

It is perhaps more a sign of the times rather than a reflection on the quality of the work that all of the winning and commended work this year was in colour. Personally I would have made some different choices, although the work of Crow and Ou did I think stand out among the rest.

We were sorry to hear that Don McCullin was unable to attend, but Tom Stoddart was there to hand over the awards to the winners. This is one of the more interesting of photographic awards, and deservedly gets sponsorship from the Sunday Times, Getty Images, Canon and Save The Children, as well as Touch Digital, Frontline Club, British Journal of Photography and, last but certainly not least, Eminent Wines.

Since I was there, I took some pictures – though using a Nikon D700 with Nikon SB800 flash and a Sigma 24-70 f2.8 HSM lens (sorry Canon!) Given all that excellent wine it is a powerful testimony to Nikon’s intelligent electronics that everything came out. The gallery was crowded for the opening, and the food and drink was still flowing freely when I left around 10 pm to scurry back to Staines.

I’ll put a few more pictures from the opening on My London Diary shortly.