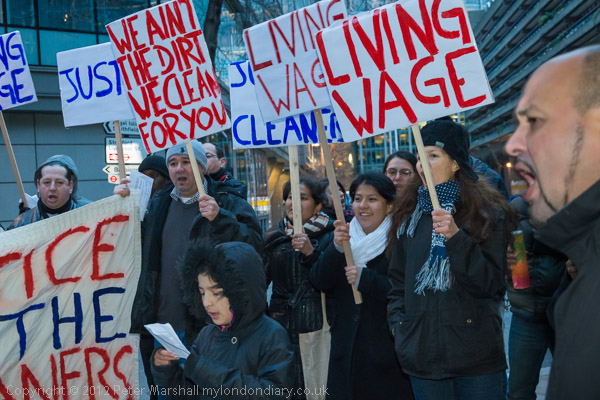

I couldn’t stay in Enfield with the Chase Farm protest because I wanted to cover the Cleaners Protest at Barbican. At least it was an easy journey, as trains from Enfield Chase run into Kings Cross, and though the Circle Line was suffering its New Zealand inspired closure so I couldn’t get the underground to Barbican, I could still jump onto the Northern line to take me to Moorgate, from where it was just quarter mile or so walk to the main entrance of the Barbican Arts Centre, a prestige arts centre owned by the City Corporation of one of the richest cities in the world, where the cleaners are paid less than the living wage.

So I was easily there at the time advertised for the protest. But there was nobody else there. I wasn’t all that surprised. Most of the cleaners are from Latin America. When I was in Brasilia, people told me that if they wanted people to actually arrive on time for an event they said “3pm English Time“.

So I didn’t assume that the protest had been cancelled and go home, but told myself I’d give it a half hour. It was too cold to stand waiting, so I went for a walk to look at an area nearby where I’d photographed some buildings and see if anything had happened to them. It was now an empty block. There were a few pubs I could have gone in, but none looked very inviting and I walked a bit more mainly to keep warm before making my way back to the Barbican. Twenty minutes after the advertised start there were now three people waiting to take part but soon a few more arrived, and 40 minutes late the organisers of the protest turned up. So perhaps I could have marched to the hospital in Enfield after all and not missed the cleaners.

Once they had arrived things got pretty animated, with lots of banners, placards and noise, including some new air-horns with pumps attached, along with a few whistles and some seriously large and loud drums. And of course a megaphone so that people going into the Barbican Arts Centre could be told why there was a loud protest taking place.

The sun we had seen in Enfield had long been replaced by thick cloud, and as the protest got under way around 4.15pm it was beginning to get pretty dark. I turned the ISO up to 1600, and working with the 16-35mm was able to work at around 1/50 f4 in the dimmer areas, going up to around 1/80 at f4.5 further away from the buildings. But people were generally pretty active although this was a static protest there was a lot of movement, and I should have used a higher ISO to get a faster shutter speed, as quite a pictures were not usuable as some of the people were blurred. The cleaners and their supporters generally protest in a very active way, with a lot of waving and shouting, and today probably jumping up and down to keep warm. The 16-35mm isn’t a very fast lens at f4, but it is usable wide open, and usually I need the depth of field that f4 gives.

With the longer 18-105mm on the D800 I was struggling even at ISO3200; I don’t like to go higher than this as the results can get noticeable noisy, but it might have been better to have done so. Both lenses do have VR, but it doesn’t seem to be as effective as it should be, and can’t deal with subject movement. Both lenses also seemed to be having occasional focus problems in the low light.

I’m still not used to the focus settings on the D800, which only has a 2-position focus switch at the left of the lens for AF-M, rather than the 3 position C-S-M of the D700, which seems much better. It’s far more difficult to change from single focus to continuous focus, and much harder to tell which of the two you are using. I can’t understand why Nikon made this change. And the three-position switch on the back of the camera was also much easier than pushing in the AF-M button and twiddling the front command dial, though this does give more options, even if I don’t know what they mean. I need to find time to study the manual again.

Eventually as it got darker still I finally had to get out my flash – still the Nissin. The results just aren’t as good, even though I was still working at high ISO to pick up as much ambient light as possible and avoid the worst effects of flash. I decided I’d done all I could and in any case it was time for me to leave and send in my stories for the day.

I’m still not sure if I prefer the Nissin to Nikon flash units. At the price it certainly does a pretty good job most of the time, and as with the Nikons I also occasionally get pictures that are ridiculously over-exposed. None of them work too well at close quarters.

I took in three Nikon flash units into Nikon for servicing thirteen days ago (I was sure I had a fourth somewhere but couldn’t find it.) The two SB800s are now repaired and I’m awaiting their return. The SB700 which I thought only needed a new flash shoe fitting – I’ve just told them to re-cycle as the estimate was close to what I originally paid for it, and slightly more than I could get a new one for on eBay. I should have tried Araldite!