The last fatal duel in England took place a short bike ride from where I live (or if I’m feeling lazy there are a couple of buses that more or less take me up the hill) ino Englefield Green, where in 1852 two Frenchmen came with their four companions to settle their differences. One of them, politician Frederick Constant Cournet, described by Victor Hugo in Les Miserables as “a man of tall stature; he had broad shoulders, a red face, a muscular arm, a bold heart, a loyal soul, a sincere and terrible eye. Intrepid, energetic, irascible, stormy, the most cordial of men, the most formidable of warriors” received a fatal wound and died in the local pub, where you can read a possibly not very accurate account of the event.

Cournet had been one of the engineers on the streets of Paris in the 1848 revolution – Hugo describes his massive barricade in the Faubourg St Antoine as “three stories high and seven hundred feet long.” He was elected to the National Assembly in 1850, but then sentenced to a year in prison for abetting the escape from jail of Eugen Pottier who later composed ‘L’Internationale‘. In December 1851 Cournet was in trouble again, having been one of the leaders of a failed coup d’état against Louis Napoleon and had to flee to London.

His opponent in the duel was another veteran of the 1848 barricades, Emmanuel Barthélemy, and although the dispute is sometimes claimed to be about remarks Cournet made about a former girl-friend of his, more likely it was because Barthélemy was a supporter of Louis Blanc, and Cournet a supporter of his opponent among the emigre French socialists in London, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin.

Duelling was illegal, and three Frenchman who got on the train at Datchet were detained on arrival at Waterloo following a message (presumably by telegraph) from the Windsor police. Barthelemey was first charged with murder, but this was later reduced to manslaughter and his sentence was a short one. But less than three years later he was caught in the act of murdering his employer and a neighbour and was hanged at Newgate in 1855. For those who are interested there is more about the duel from the trial (in brief, Cournet fired first and missed, Barthélemy had the second shot, but his pistol did not fire – so Cournet lent him his, and was then fatally wounded) as well as information about the murder on a rather grisly site, Execcuted.Today.com.

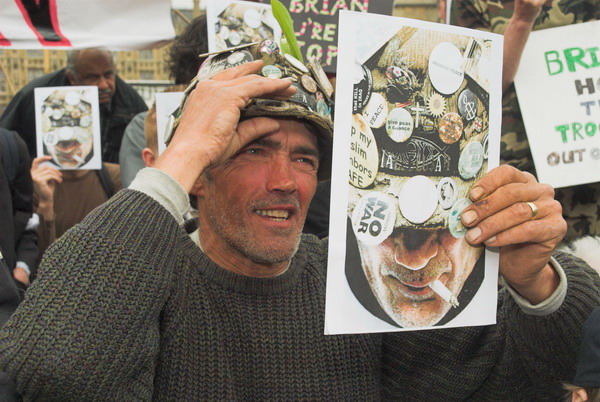

All this came to mind (and prompted a little research, though I’d read the not entirely accurate account inside the bar of the Barley Mow a while back) when I went to photograph a protest by the oddly named JENGbA, short for Joint Enterprise – NOT Guilty By Association, a campaigning group against the injustice of ‘Joint Enterprise’, an offence said to have been “introduced three hundred years ago in a clamp-down on dueling, enabling the seconds and doctors who attended duels to be arrested as well as the actual duelists.”

Being Common Law rather than defined by any statute the exact history is hard to trace, though there are a number of key cases which serve as precedents to define it. But its Common Law orgin also renders it liable to be misused and subject to political pressures on those responsible for prosecutions who attempt to widen its application. What makes good sense in very limited circumstances has over recent years been expanded into a catch-all offence in what is seen as a war on gang killings. Surprisingly there are no official statistics, but through freedom of information requests researchers concluded recently that more than 1,800 people had been charged with homicide (and many convicted) under joint enterprise in the previous eight years.

I was shocked when I read about some of the cases of injustice that JENGbA has taken up, one or two of which I mention in My London Diary. Although there has been considerable disquiet over this in legal circles with a Bureau of Investigative Journalism study and a report by the House of Commons Justice Committee, there has really not been the public outcry that it demands, probably because most of those convicted come from disadvantaged groups and many are tarred, often inaccurately, with belonging to criminal gangs.

It is just one other aspect where ‘British justice’ no longer meets the standards we used to believe in – as too are the police killings of suspects during arrests like that of Mark Duggan and the many suspicious deaths in custody.

Obviously I wanted the Houses of Parliament in the background, but also carefully framed for the shadow at right

Photographically the main problem I had in covering the march by JENGbA was one of contrast, with the low sun often seeming to come from exactly the wrong direction for my purposes. Of course I should probably have used some flash fill, but somehow I felt this might be a little intrusive and upset what felt like a rather delicate relationship between me and the families involved in the protest.

I’m also getting a little worried about the 16-35mm lens. It does seem to be giving far more flare than it used, and I wonder if it is in need of a good clean. But given the bill I got the last time I took it for repair I’m not keen to repeat the experience, particularly when I’m not quite convinced it is necessary.

I do seem to get both more specular flares (aka ghosts), bright spots of light, sometimes coloured and often hexagonal, and also more veiling flare, the diffuse creeping of light from over-bright into shadow areas of the picture.

Ghosts sometimes add a little to the image and are usually difficult to remove or ameliorate. Somtimes it is possible totone them down a little. Small ones entirely in areas like sky can be cloned away if necessary. With the diffusion, using an adjustment brush on the affected area to increase contrast, reduce highlights and increases clarity can help, sometimes with a slight positive or negative exposure change. I’ve tried to do this, perhaps a little clumsily on the head of the leading figure with a megaphone on the top image in this post.

Shortly after the start of the march, it came across the rather macabre site above on the pavement, in an area well away from any buildings in front of the large yard of Chelsea College of Art.

More about the march and a little about some of the cases at Joint Enterprise – NOT Guilty By Association.

Continue reading Joint Enterprise