Vivandière (French cantinière) Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. with Fenton’s crop marks

It was back in the 1980s that I got briefly into salt printing (more on that here), around 140 years after W H F Talbot showed us the way (possibly picking up the idea from Sir Humprey Davy) in 1839, and with his ‘The Pencil of Nature‘ (1844 to 1846) published the first major printed work incorporating a number of them with his ideas. I wrote briefly about the salt print process back in the 1990s, and published a revised version in the following decade with my own illustrations. I’ll try and find it and republish, but the truly definitive work on the process, Reilly, James M. The Albumen & Salted Paper Book: The history and practice of photographic printing, 1840-1895. Light Impressions Corporation. Rochester, 1980, is available free on-line for those who want full details.

Its a process you can read about in most if not all the histories of photography, and there are many manuals available in print and on-line to tell you how to do it apart from the Reilly book mentioned. In some it will be called ‘plain paper’ printing or just ‘silver’ printing and it was performed in the 1840s and 50s making use of ordinary writing or drawing paper of the age, which was first coated or soaked in a salt solution (sometime common cooking salt, sodium chloride, though other salts were also used) and then after having been dried, made light sensitive by floating on a bath of silver nitrate solution (or this could be brushed on.) The paper then had to be dried in dim light and exposed with as little delay as possible in contact with the negative in a printing frame in sunlight.

The papers used were only lightly ‘sized’ or coated with a material – usually gelatine or starch – and the solutions soaked into the paper, with the light sensitive silver chloride (or other silver salts) being embedded into the paper. Later photographers began to use more sizing or other materials to keep these salts on the surface which enabled a better tonal range. The most successful of these was albumen (egg white) and as well as making matt surface prints this also enabled prints to be given a glossy finish. It used to be a standard museum practice to label all early matt prints as salted paper and early glossy prints as albumen.

Many photographers continued to make their own salted paper into the early years of the twentieth century, with directions still being published in various manuals of the times, although by then there were many commercial alternatives. You could also buy papers that were ready salted and only needed the photographer to sensitise them, but there were also other alternatives for the photographer. In a 1910 issue of ‘The Photo-Miniature, the author writes “Twenty years ago, when photography was not a popular pastime but a mysterious hobby, a photograph could be only one definite thing, namely – a so-called silver or albumen print.” (This refers to albumen prints only, not to salted paper prints.) The title of the article ‘The Six Printing Processes‘ gives us some idea of how much things had then changed since 1890, although there were many other processes also in use by then, some dating back to the beginnings of photography such as the blueprint (aka cyanotype.)

I was reminded of all this while eating breakfast this morning by the Today programme which featured two people talking about Salt and Silver: Early Photography 1840 – 1860 which opens to the public at Tate Britain tomorrow (25 February – 7 June 2015) with a claim to be the first exhibition in Britain devoted to salted paper prints. While this may be strictly true, many shows have included works from this period, many of which will have been salt prints, and other shows focussing on particular photographers or groups have been entirely of salt prints. But this is the first to be actually built around the process and while the show appears to include some well known works, it also brings out some less familiar.

The text also states “The few salt prints that survive are seldom seen due to their fragility, and so this exhibition, a collaboration with the Wilson Centre for Photography, is a singular opportunity to see the rarest and best early photographs of this type in the world.” Silver is a fairly reactive metal and much of the early research into different printing methods was aimed at ways to prevent the fading of images, particularly from an age where the necessity for thorough washing of prints was not fully appreciated. I don’t think salt prints are rare, but examples from this early period, and particularly ones in good condition perhaps are. But prints by WHF Talbot regularly appear in auctions and even in recent years some have sold for well under £5000. My own salt prints, now around 20 years old, are still looking much the same as when I made them, but may well not last 170 years. As to whether these are the best, you will perhaps have to visit the show to find out, although the works selected to display on the web site by Hill & Adamson, Talbot and Fenton are certainly not those I would have chosen.

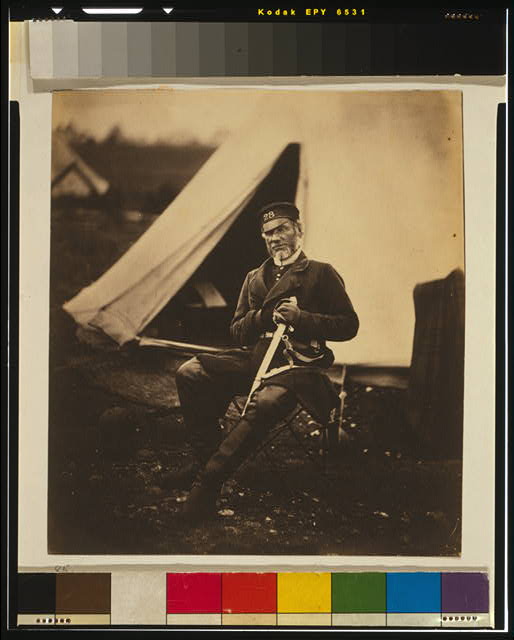

Captain Andrews, 28th Regiment

There are two included in the on the Tate web site by Talbot, and also two by Roger Fenton, who made both albumen and salted paper prints. There is a marvellous collection of 263 of his Crimean War pictures at the US Library of Congress, which includes prints of the same two reproduced here. You can if you wish download high resolution TIFF files of these (Vivandière is called Cantiniére on the Tate page) and print out your own copies, either on an inkjet or, if you really wanted, convert to a negative to make your own real salt prints. It really isn’t too difficult!

One thought on “Salt Prints”