Like many with an interest in photography I’ve been reading the blogs and reviews from this year’s Arles Rencontres and from what I’ve seen I’m pleased I didn’t make the effort to go there. But one show I would like to see opened recently at the Met in New York, Hipsters, Hustlers, and Handball Players: Leon Levinsteins New York Photographs, 1950-1980.

Levinstein was really the guy who wrote the book of what we now call ‘street photography’, so perhaps it’s rather unfair of Ken Johnson in the New York Times to denigrate the show as “a compendium of street photography clichés.” Much of it only became clichés because others followed his lead. But then I find it very hard to take with any seriousness the writing of someone who can describe Tina Modotti as “a master of the genre” along with Weegee and Robert Frank. This isn’t by the way a criticism of Modotti, though I’m not her greatest fan.

Gallerist James Danziger presents a markedly more sympathetic view, though I’d take exception at his suggestion that Levinstein is “more known and appreciated by dealers and curators than collectors or even photographers“, as I think more than almost anyone else I can think of he is a “photographer’s photographer”, (as indeed the Economist describes him in a short piece with a small set of images from the show) but although I’ve not seen the show I do know his work and Danziger is spot on when he says “hes the real deal.”

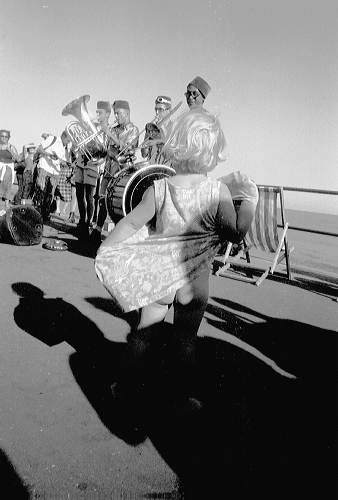

Vince Aletti in The New Yorker gets to the nature of the work well when he talks of Levinstein as a loner “communing with New York at its grittiest, clearly relishing the experience” and producing work that is “brutal, brilliant, and uncompromising.”

In the Village Voice, Robert Shuster picks it as the only photographic show in his art recommendations and in a short piece compares him with Frank and finishes with the statement “Levinstein deserves wider recognition for recording the fleeting, quirky scenes of city life.”

The Met now has a decent short piece on him on their site, the real gem of which is a po0dacst with exceprts from a 1988 archival recording in which Leon Levinstein talks about his work.

The Howard Greenburg Gallery site isn’t my favourite – in my view a rather bad use of Flash, and if you have a recent Flash version installed you may well be told you haven’t got the correct one, but it will still actually work if you tell it you have. Under the ‘Artist’ tab if you scroll down you will find Levinstein and eventually a set of around 40 of his images.