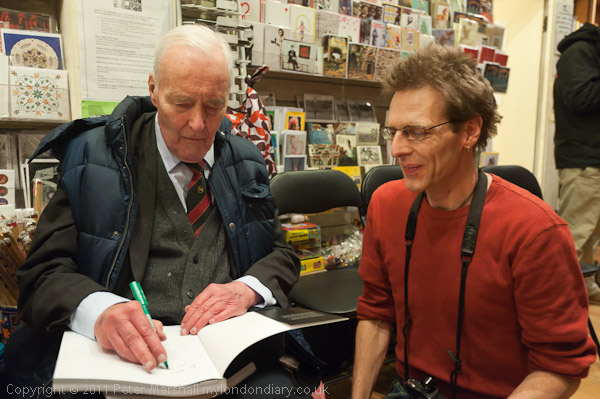

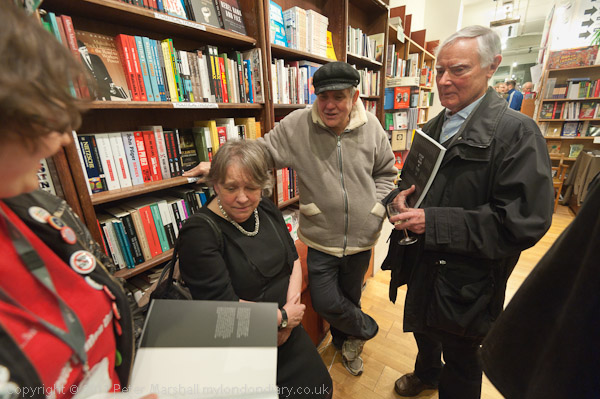

I didn’t go out specially to take these pictures in an area of London I’ve hardly visited since I photographed it around twenty years ago and got to know fairly well. One friend who I often meet photographing events in London, Medyan Dairieh, was showing his prize-winning work from Libya. Working for Al-Jazeera, he covered the Libyan revolution very much from the front line, entering Tripoli with the anti-Gaddafi forces and being wounded for a second time in the siege of the final stronghold of Abu Saleem.

Medyan has already talked about his work in Brighton and there are plans for further showings of his photographs and video in other cities. Al-Jazeera has built up a reputation over the year for its reporting of events in the Arab world that has made the BBC and others look hopelessly out of touch and sometimes biased, and Medyan’s photography has played its part in their success.

Unfortunately I couldn’t attend the main event yesterday evening, but took a rather lengthy route home after photographing yesterday’s Climate Justice march to call in, look at the work and meet Medyan again, looking quite different in a smart suit than when we meet on the street, fairly late in the afternoon. It was more or less dark when I arrived at the show, and certainly night as I left at around 4.45pm, almost an hour after sunset.

_____________________________________________________________

The event took place in Park Royal in north-west London, developed as London’s largest industrial estate in the 1930s. I think I first went there when Prime Minister Thatcher had just turned her back on British manufacturing industry in favour of banking, the city and services, photographing a bleak factory for sale on a snowy day as a part of a project on de-industrialisation, returning in later months to photograph some of the more interesting industrial buildings that I thought might soon be demolished.

I’d hurried past a small group of buildings as I came to the Islamic centre hosting the event that I had thought might be interesting to photograph, but hadn’t wanted to stop. As I walked from North Acton station I’d been thinking it would be interesting to visit the area again and photograph in better light. But when I came out, the light, mainly from the street lights, with a little still from the dark blue sky wih a few clouds, and also from the passing traffic, was creating a rather interesting and somewhat unearthly effect, so this time I stopped to take a few pictures.

It wasn’t a brightly lit road and I didn’t have a tripod. But nowadays that is seldom a problem. ISO 3200 on the D700 gives a nice quality, with a slight noise which is hardly noticeable at normal scales and quite attractive at 1:1. The 16-35mm lens is only f4, but even at 20mm I would want to stop down to at least that aperture for depth of field in an image like this. Without any exposure compensation set, the shutter speed of 1/30 was hardly a problem, though I made several exposures to be sure to get one that was critically sharp. The Coca-Cola can in the foreground just to the right of the tyre may not be visible on the web, but at 1:1 it is sharp, as is the text across the front of ‘The Kiosk’, though certainly this is easier to read in the second image from closer side.

To get similar results using film would have been difficult. I would have had to stick to a relatively slow emulsion, perhaps ISO 200, making a tripod essential, made calculations and then bracketed to cope with reciprocity failure, fiddled around with correction filters and then have kept my fingers firmly crossed until the prints came back from the lab, usually requiring a reprint to get the kind of results I wanted. Even then they would have been nothing like as good a colour quality as we routinely get from digital. Though some people like the odd colour that film produced; rather like those people who prefer their oil paintings seen through discoloured ancient varnish than after restoration, or their buildings before rather than after the years of pre-Clean Air Act grime has been removed (and sometimes I do too.)

I could remove the orange cast from the images too, but the orange light was a part of what attracted me to the scene, and removing it produces an unnaturally cold effect. I have reduced it a little from Nikon’s automatic white balance that I used when taking the picture.

Earlier in the day, as I’d been photographing the march looking down on it from Waterloo Bridge, I’d been quite surprised to find a photographer next to me using a tripod. I was getting shutter speeds of around 1/400th and using the 18-105mm felt no need for a tripod, particularly as I was leaning on a very solid railing to take my pictures.

Back in the old days of film, I would only have needed a tripod had I for some reason chosen to photograph the event on a slow film, such as Pan F or Kodachrome 25. Though I can’t ever think why I would have done so when Tri-X or Fuji 400 would have done a better job. But with digital, tripods are needed so rarely that I’ve almost given up on them completely. Tripods still have their uses, but mainly no longer to hold the camera steady (they have never ensured sharpness!*) I think the only use I’ve made of one in the last year has been to mark an exact spot in space to use when rotating a lens around its nodal point to make a panorama – which I was actually taking hand-held. The main rationale of a stand or tripod in a studio is also to precisely locate a camera.

I think there is a stage in photographers’ lives where tripods seem important and seem to them to mark themselves out as a ‘proper photographer’ – and for some years I went nowhere without one. But technology has changed and in practical terms they are now seldom more useful than a dark cloth. And yes, I’ve seen a photographer with an ordinary DSLR using one of those as well. Probably the moth has got mine by now, stashed away in a cupboard with one of my 5x4s. Doubtless there are still photographic courses where students are urged to use tripods, told that you need them to get sharp pictures, just like many are still told nonsense about film being better than digital, that darkroom prints are always better than inkjet prints and doubtless much other nonsense.

Strolling a few yards further on I came to the bridge across the canal. Park Royal had a great location for industry because of its situation between two of the main rail lines out of London, the Grand Union Canal, and road links including the A40 and the North Circular Road, though now I imagine only the roads are significant. It was really dark as I looked along the canal, hard to make out the two railway bridges. This time there was hardly any light at all, and one solution would certainly have been a tripod. But I held the camera on top of the flat metal of the road bridge and gave a six-second exposure. It was so dark that I didn’t notice the group of people on the canal towpath until after I’d take the first exposure.

On the back of the camera, the picture looked far too light, so I made a second exposure for half the time. Lightroom’s auto setting produces more or less identical results from the two, simply adjusting the exposure values. Theoretically the longer exposure should be a little less noisy, but I couldn’t actually see a difference, but surprisingly it was just a tad sharper – probably a heavy vehicle had shaken the bridge a little during the shorter exposure (another thing tripods don’t control.) Using the default values actually produces a picture that looks more or less as if it was taken on a sunny evening, the orange street-light becoming warm sun. I’ve tried to get to something a little closer to what I saw and felt as I took it.

__________________________________________________________

* I may sometimes have felt it would be useful to stuff some of my subjects, sometimes not only for photographic purposes, but it has never proved practicable, and a little selective unsharpness often improves images. The second major cause of unsharpness in my images is incorrect focus. Camera shake comes a poor third except where I’ve forgotten to set an appropriate ISO. Which happens. Too often.