A video on ASX of Eikoh Hosoe, a leading figure in Japanese photography talking about his work and inspirations at the launch of the exhibition ‘Eikoh Hosoe: theatre of memory’ at the Art Gallery of NSW in 2011 brought back some fond memories from meeting him in 2005.

We both had shows as a part of the first FotoArtFestival in Bielsko-Biala in Poland, which brought together work by 25 photographers from 25 countries around the world along with a group show of Polish photoreportage of the 1970s and 80s. It was I think a deliberately eclectic selection, including different types of photography and photographers of all ages, including a few no longer living – Inge Morath, Russian war photographer Robert Diament and Mario Giacomelli, and a mixture of well-known names and relatively unknown photographers including me.

Many of those still living had come in person to the festival to talk about their own work, and in addition I’d offered to give a couple of lectures – one on the work two rather different British photographers who had influenced me, Tony Ray Jones and Raymond Moore, both of whom were more or less unknown in Poland at the time (and Moore still is, largely because his work is still inaccessible, but Ray Jones was featured in a festival at nearby Krakow a couple of years later), and the other on the work of some of my photographer friends in London. It was something of a disappointment that neither Boris Mikhajlov and Malick Sidibe were able to attend, but great to meet the others – including Eikoh Hosoe, certainly the best known of those present.

Here’s what ASX says about him:

“Eikoh Hosoe was born in Yonezawa, Yamagata in 1933 and graduated from Tokyo College of Photography in 1951. He exhibited in his first solo show in 1956 and has since established himself as an internationally acclaimed photographer. Hosoe’s figures have a Surrealist quality that is startlingly intimate, yet also render the flesh abstract and strange.”

I don’t think he was present for the initial press conference, an interesting event for me when I found myself under attack for Britain’s colonial past by one of the other photographers who had been liberally enjoying the local hospitality – I’d decided myself that the only way to survive was never to drink vodka, a resolution I think I almost managed to keep. In an exchange (which I don’t think was entirely followed by the local press) I told him that those very same people who had screwed his ancestors had liberally screwed mine too, and after a little argument we became good friends – and afterwards I helped him down the street to another bar along with some of the other photographers.

Eikoh Hosoe, Jutka Kovacs and Stefan Bremer at the reception in the castle

It was later after a grand opening ceremony with projections of the our images to a fantastic live piano accompaniment by Janusz Kohut that I first met Eikoh as we both made our way out into the foyer on the way to a party at the castle. I went up to him and told him how much I liked his work and that I’d been an admirer of his work and had written about it – it must have been a rather embarrassing moment but he remained charming and extremely courteous.

Eikoh Hosoe, Ami Vitale and me at the meeting: photo by Jutka Kovacs

Being 72 at the time (born in 1933) he didn’t join the group of photographers who went to a local bar when the wine ran out (there was still vodka, but I expect he needed some rest.) But probably his head was rather clearer than most of us the following morning for the start of the ‘author sessions’ where the photographers talked about their work, and clearly took a great interest.

The next day the sessions all overran, and everyone decided a break was needed before my rather long performance, talking about my own work as well as the two short lectures, though I’d rather have got on with it. A group of the photographers went together for a pizza, and took him along with us. A beer or two helped to steady my nerves too, and we all indulged in taking silly pictures of each other as we waited for the food to come.

The pink phone was the only camera Eikoh Hosoe had with him, and I think it was a new toy, Fortunately someone was able to show him how to see the pictures he had been taking (which he hadn’t found how to do) and above you can see his reaction.

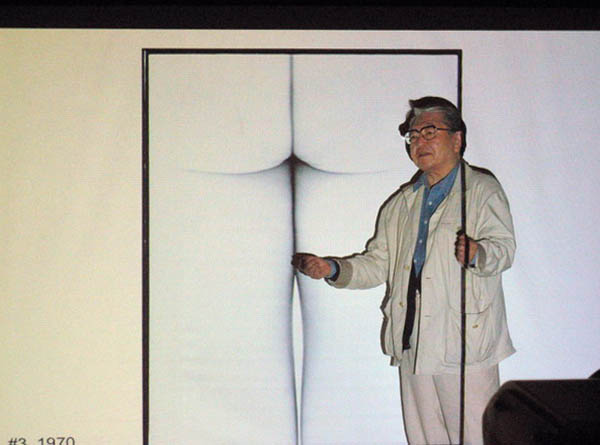

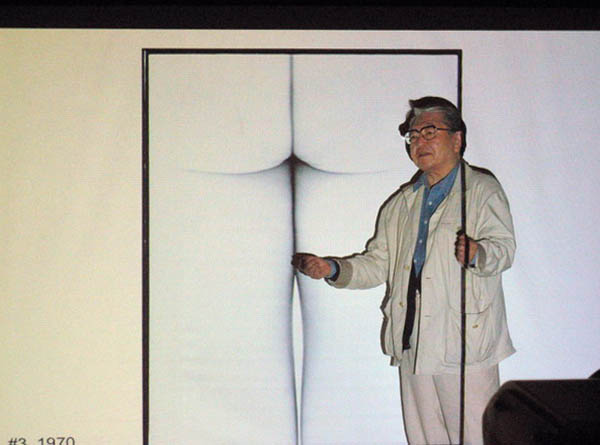

Later, after my talk, and another by Stefan Bremer, it was his turn to present work as the finale of the event. The light in the large hall came from the computer projector, and Hosoe moved into it on various occasions to talk about the work. I tried hard to catch him at just the right moment, and I think the image below was my best attempt before the battery on the small compact Canon Ixus ran out.

Eikoe Hosoe makes a point about one of his pictures

You can see a good selection of Hosoe’s work at the Howard Greenberg Gallery site. There are some more pictures with him in – as well as many others – in the FotoArtFestival Diary I wrote when I was in Poland, and I’m pleased to see that at least some of the links to the Wayback Machine with the posts I wrote at the time for About.com are now working again.

Continue reading ASX Eikoh Hosoe