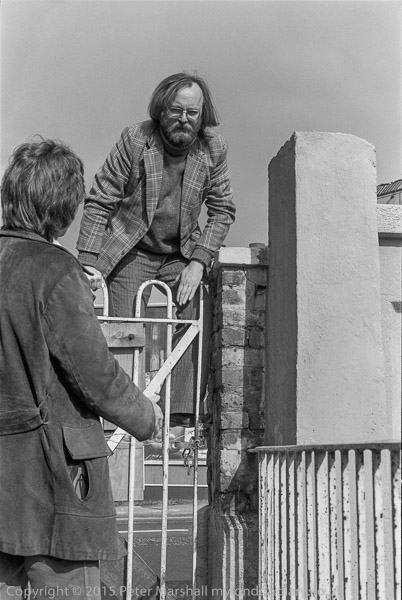

Way back in the mists of time – and 1979 now seems pretty misty in my memory, I took this picture of the late Terry King clambering over a gate with some difficulty. While another photographer, Robert Coombes, was going to help him, I simply stepped a little to the side to take the picture. It was a matter of priorities!

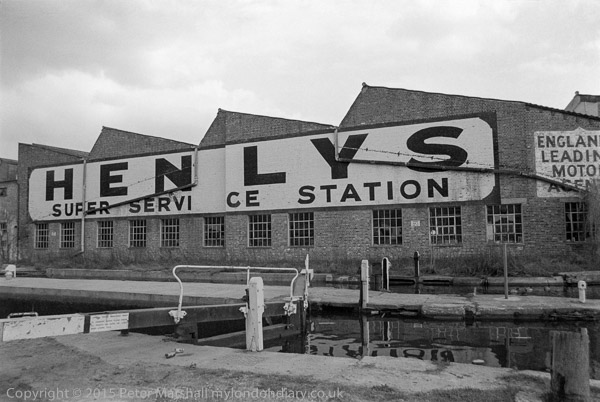

We were on a Group 6 outing on a fine Sunday in May and I think we had probably caught the North London Line which at that time ran from Richmond to Broad Street station with some of the dirtiest trains imaginable with windows that had almost certainly never been cleaned since they were put into service perhaps 40 or 50 years earlier, and a peculiar musty smell.

Terry was the organiser of our group, then at least nominally a part of the Richmond and Twickenham Photographic Society, though we later were forced to leave, and to change our group name to Framework. Although a fine photographer, making some exquisite gum prints (one of which still hangs on my wall) and a poet – you can see both aspects in his Beware the Oxymoron, he was an aesthete rather than an athlete, although in his civil service job before he went full-time into photography he had at one time had to clamber down somewhat rickety ladders to inspect tin mines.

I think the canal walk had probably come from a suggestion by me, as a few months earlier I’d taken a couple of walks on my own along the Grand Union and would have brought some of the prints to show the group. As well as the visual possibilities I was excited by the way it cut an almost secret path through the city, and there were also strong connections with my then growing interest in industrial archaeology. But Terry knew the canals better than me and was the leader for this outing.

The canals were less well-known then, and also rather less used. Commercial traffic had more or less come to an end, and the leisure boating community was much smaller than it is now, and much less public, almost masonic. There were fewer people actually living in boats. I used occasionally to ride my bike along a tow path, and it was then illegal unless you had a permit, for which you had to pay; you had to keep an eye open and avoid the wardens. Later the British Waterways Board decided to make these permits free – and I applied for one straight away, and used it until permits were no longer necessary and the tow-path became free for all. On many London stretches it is now too much of a free for all, and just a small proportion of the cyclists who use it do so irresponsibly at speeds more suitable for a racetrack than a shared path.

But our outings were not intensively planned. We had a meeting point and a rough idea of where we would go, and then wandered. It was a small but diverse group photographically and the handful – seldom more than five or six – who went on any of our meanderings had interests in different aspects of the subject matter and often very different equipment – from 35mm up to 4.5″ and later even 8×10″.

As a result of our lack of planning, when we got to the canal, we found it was closed. Not closed to boats, but the tow-path was closed, and the gates to it locked. Work was going on to put high-voltage cables under the tow-path.

But it was a Sunday, and no-one was working, so we climbed over the gate and had the canal to ourselves to take pictures. We did have to walk carefully around some areas where there was a trench dug for the cables, but there was no real danger. Eventually we did come to a place where the tow-path became impassible, and worried we might have to walk back some distance to the gate we had climbed over, but fortunately a woman who was in her garden backing on to the canal came to our rescue, and let us in through her gate from the tow-path and through her house on to the street.

She was cradling a young child, her grand daughter, and as we thanked her outside her front door, I asked if I might take a picture of the two of them and she agreed. Her friend was standing watching from the door step. I didn’t photograph many people outside my own family at the time, and this remains an image that I like. A month or so later I tried to return to give her a small print, but either I’d remembered the address wrongly or they had moved. I think I went home and posted it, hoping it would be forwarded.

I’m working on these images in preparation for another book, of my walks along some of London’s canals back in the late 70s and early 90s. Probably most of these images will appear in the book, but I’ve yet to make the final selection.