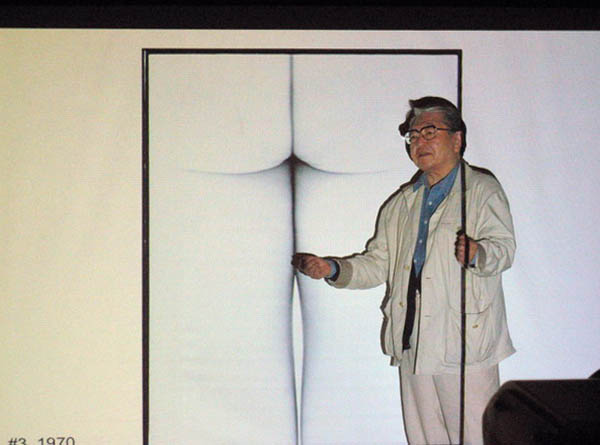

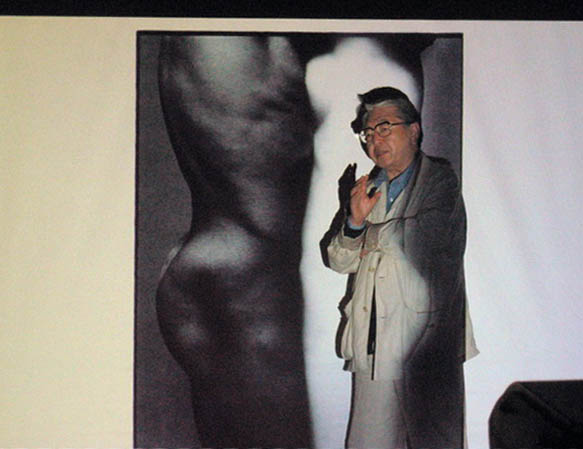

Eikoh Hosoe and one of his pictures from Ordeal by Roses

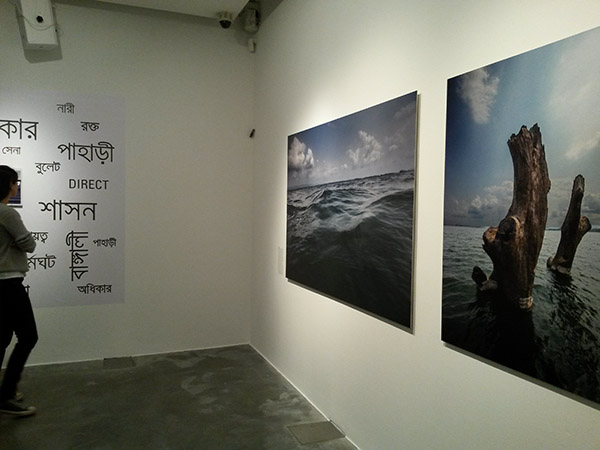

Today’s L’Œil de la Photographie with its article Eikoh Hosoe, Barakei A portrait of Yukio Mishima brought back memories to be of a few days spent in company with him and other photographers back in 2005 in Bielsko-Biala, at their first FotoArtFestival.

Eikoh Hosoe in Bielsko-Biala

It was a great privilege for me to be invited to show some of my urban landscape work from London’s Industrial Heritage along with such distinguished company as Eikoh Hosoe, Ami Vitale, Boris Mikhajlov and Malick Sidibe, as well as many rising stars and a few of those no longer with us, Mario Giacomelli, Inge Morath and Robert Diament, as one of 25 photographers representing 25 countries around the world.

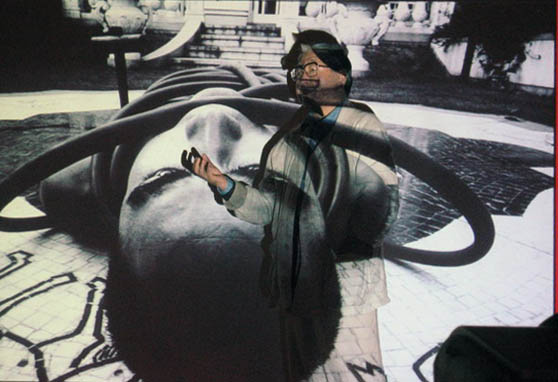

Eikoe Hosoe uses his pink phone camera

I’d travelled light to Poland, and had only taken a small digital pocket camera, a Canon Ixus. It was an excellent camera for the time, but in some of the dimly lit interiors I did find myself wishing I had brought a Nikon. But it was a small and pocketable camera, and I think did remarkably well all things considered. You can see more pictures I took with it on the trip in my FotoArtFestival Diary, along with some of one of my three talks there. As well as presenting my own work, I also gave presentations on the work of two great British photographers, Tony Ray Jones and Raymond Moore, and on the work of some of my London Friends, Paul Baldesare, Jim Barron, Derek Ridgers, Mike Seaborne and Dave Trainer.

Eikoh Hosoe photographs me photographing him

What was remarkable apart from the photography was the atmosphere and camaraderie among the group of photographers there, some of the exhibitors and a few of their friends. Any ice between us had been broken at the press conference, which was enlivened by vitriolic attack on me as a British colonialist by one vodka-fuelled photographer as I got up to speak, enabling me to reply with a robust statement of some of my own political views and working class background, a family history of being screwed by that very same ‘elite’, ending up with us embracing each other – and going to a bar with most of the other photographers. Though I stuck firmly to my own resolve not to drink vodka, the beer was good.

Eikoh Hosoe

Hosoe was certainly the most distinguished of the photographers present, and probably too the oldest, and had a typically Japanese quiet reserve which was rather at odds with his photographic work. Though as some of these pictures show, by the end of the event he was very much one of us.

Eikoh Hosoe shows a picture on his pink phone

The ‘Eye of Photography’ feature accompanies a show of the work Bara-kei, (1961–1962) more often known in English as ‘Ordeal by Roses’, homoerotic images of melodramatic poses by the writer Yukio Mishima, one of Japan’s leading postwar writers, also a poet, playwright and actor as well as a nationalist who founded his own small right-wing student militia, the Tatenokai, taken in Mishima’s own house in TOkoyo. His work set out to break taboos and upset cultural traditions, with an emphasis on sexuality, death and political change, a delusion that led in 1970 to him with just four of his militia to perform a coup attempt to restore the power and divinity of the emperor, thought to have been a dramatic staging for his own ritual suicide with which it ended.

Eikoh Hosoe talks about one of his pictures

The Show ‘Barakei – Killed by Roses’ is at the Galerie Eric Mouchet in the Rue Jacob in Paris from today until December 23, 2016.

and another

You can see and hear him talking about some of his work in a video made for the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

There is a good selection of his work on Artsy – or you can search on Google Images. Although his work is on many gallery sites he does not seem to have his own web site. He has been the director of the Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Arts since its foundation i 1995. There is a nice piece on him, Eikoh Hosoe – Kamaitachi – From Memory to Dream by Rob Cook in The Gallery of Photographic History