The idea that we are all equal under the law is a vital part of our understanding of human rights and equality, but it hasn’t always been like that (and still isn’t in some respects.) At least until relatively recently in the UK, some of the medieval privileges of the church still gave clergy (or at least Church of England clergy) some special protection, and institutionally the Christian churches are still protected by laws such as our blasphemy laws.

On Saturday, Peter Tatchell reminded us that the church still enjoys some extra protection, and that he had been convicted under the 1860 Ecclesiastical Courts Jurisdiction Act after his Easter demonstration in Canterbury Cathedral – and he was fortunate to be up before a judge with a sense of humour, who fined him £18.60 for the offence. And at the same event, Liberal Democrat MP Evan Harris told us of the need to repeal the Blasphemy laws (and he’s tried.)

But although ‘One Law For All’ is against all religion-based law, it’s main focus is on Sharia law, because of the special position it has in many majority-Muslim countries around the world, but also because of attempts to introduce it – if only on a voluntary basis – into the legal framework of countries including the UK.

The problem with Sharia – as with our largely vestigial religious laws – is that it was conceived in a very different society to that we live in. At the time it represented a radical and forward-thinking approach to issues of justice and the rights and responsibilities of men and women compared with the then current practice. But times and societies have changed dramatically since then so that the views codified then no longer represent the kind of spirit and way of thinking that they then did. Laws need to evolve as society evolves or they become ossified into reactionary and outdated practices.

The idea that disputes in 21st century Britain should be settled by rules fixed absolutely more than a thousand years ago in a very different feudal society is untenable.They conflict with the ideas that have developed since about human rights in general and about the equality of women in particular.

The use of Sharia law is no more acceptable than would be tribunals based on fundamentalist Christian precepts or indeed those already existing of the Beth Din, although I think it is beyond dispute that our ideas about human rights and the value of human life have been very much influenced over the centuries by the insights of all three religions. And while I found myself very much in agreement with the aims of the ‘One Law For All’ campaign there was a kind of sectarian anti-religious fervour from some of its supporters that I found both a distraction and a detraction from its purpose.

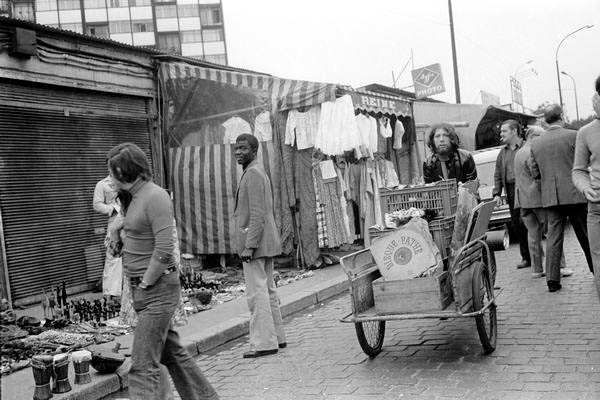

Photographically there were few problems with what was a relatively small event – a couple of hundred people, including a very large number of speakers. It was perhaps difficult to know how to make use of the row of small coffins in front of the main banner and hard to incorporate them with the speakers; shooting wide enough to get them in made the speakers on a small podium a few metres further behind rather small, and moving further back to cut down the effect of the different distances wasn’t possible as the audience was in the way.

I did try to use just the words ‘NO SHARIA’ from the banner with some of the speakers, but it wasn’t very exciting. But there was considerable freedom to photograph them from different angles and distances and I felt I did get at least one decent picture of almost all those who spoke.

One Law For All does have some graphically very strong placards, but it was perhaps a pity that there were not rather more of these. They worked rather better in the demonstration in Trafalgar Square last year where they formed a good background to many of the speakers. But I did get a few pictures I liked of the audience.

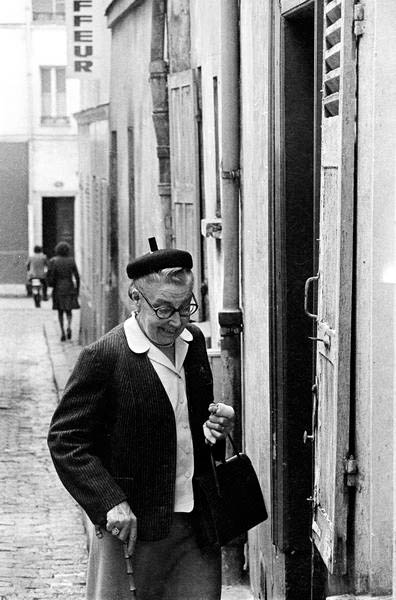

Partly because I was still feeling a little drained after the flu, I’d lightened my camera bag by taking only the D700 body and a few lenses – the 24-70mm, 10.5mm fisheye, 20mm and a 55-210mm. I took a few pictures on the 20mm, but nearly all on the 24-70 and 55-210, and kept finding myself wanting to change between these two. It would have been a lot easier with two bodies.

Part of the reason for the frequent changes was simply the very large number of speakers – and I’d decided I would photograph each of them. In most cases I took both full length pictures with the wider zoom and also fairly tight head shots with the longer lens.

I haven’t cropped or corrected the vignetting on this image

The 55-200 Sigma is a ‘DX’ format lens, but certainly at the longer end seems to cover the double size FX frame with decent corner to corner sharpness, certainly good for portraits. At the wider end it does vignette slightly (and I had to saw a little off the lens hood which vignetted even more than the lens) and at 55mm I have to crop the frame by a couple of millimetres, but it still gives a reasonably sized file. Its big advantage so far as I’m concerned is its weight – a ridiculously featherweight 335 g.

There is a little more about the event and a few more pictures in my account on Demotix, more to follow on My London Diary