“Isn’t it a thrill to have him here in London” said the woman behind me to a friend as we we all waited, hardly an empty seat in the small lecture area of National Geographics’s Regent St first floor, and the next hour or so listening to Shahidul Alam talking, showing pictures and answering questions certainly justified her anticipation.

Probably most of us in the audience had some idea of the incredible transformation Dr Alam has made to the world of photography, not just in his native Bangladesh but worldwide, although so much still remains to be done, but I think all of us found there was even more to him – and his family – than we had been previously aware.

Alam’s mother in particular was a formidable woman; determined to get a university education despite the opposition of her mother to the education of women, she left home every morning in a burkha “going to visit friends” and went to study. Armed with her degree she dedicated herself to the education of women, and having found little backing for her project, bought a tent and used it to set up her own school for girls.

Later too we heard that his father had dared to evade the “invitation” sent to him along with the other leading intellectuals of the country to take tea with the occupying Pakistani generals in 1971 just a few days before the end of the war. It was a story accompanied by a picture by Rashid Talukdar of a severed head in rubble, from the killing fields of Rayerbazar. Altogether more than a thousand teachers, journalists, doctors, lawyers, artists, writers and engineers were massacred.

Shahidul Alam was sent to study chemistry in the UK in 1972, gaining his Ph.D in London, and taught the subject while at the same time developing an interest in photography, at first making camera club style pretty pictures. But then he came across photographs that were harder to understand and seemed to have more depth – such as Steichen’s ‘Heavy Roses’, said to be the last picture he took in France in 1914, sumptuous but slowly decaying and fading as the Great War started – and began learning to see and to work at finding out what was interesting about such less obvious pictures. While living in Kingsbury in Northwest London he photographed people in his locality and took them to the local paper, who published them as a spread on the back page and paid him a tenner for them (a local paper paying – how times change!) – his first professional work.

He had (and still has) a particular love of photographing children, and having seen that a child portraiture studio – Young Rascals Studio in Acton – wanted photographers he went for an interview and got the job, and was soon the most successful of their photographers, earning around £350 a week, a pretty good wage at the time.

After a while, although he was doing well financially he decided that what he was doing was not something he wanted to devote his life to, and he made up his mind to return to Dhaka with his savings of £2800, and go back and live with his parents and try and become a photographer and take part in the life of his own country . It wasn’t easy to find any employment there, so he set up his own business as a photographer as well as starting to teach photography and work with communities.

Alam was at pains to point out that he had no problem with white western photographers coming to photograph in his country, but that he felt that photographers from countries in the majority world had an understanding of their own communities that provided them with a different viewpoint. He wanted a pluralistic world in which different people got to tell stories, but was against the kind of monopolistic view that media around the world tended to project of countries like his own. This was brought home strongly to him while on a visit to Northern Ireland when a five-year-old showed her surprise at seeing him playing with a few coins. Even at that age she knew that people from Bangladesh didn’t have any money.

Increasingly too he began to question his own position in his own society, as a middle class man with a camera – and characteristically began to do something practical about it. In 1994 he set up a women’s’ photography group, bringing a woman to the country to teach them, and he also began teaching photography to classes of working class children. He then set up the Pathshala school of Photography, now recognised as a world-leading school for photojournalism, with its students and ex-students gaining exceptional success in international competitions. It is also possibly unique in that all of those finishing the course have found work as photographers, though Alam did say that the market for photographers in Bangladesh was now becoming saturated and he was having to think about encouraging some students to work in ancillary professions such as picture editing and picture research.

It was great to see in his photographs and a short film clip how photography was being taken to the people in Bangladesh, with mobile exhibitions mounted on bullock carts and cycle carts being taken into villages, and also the work with village children. Alam also founded and directs the Chobi Mela international festival of photography held in Dhaka every two years which he set up is the largest photography festival in Asia and takes photography out on the streets (and on a boat) with a very different atmosphere to most festivals.

Through his photographic agency Drik, (now part of a wider multimedia organisation) set up in 1989, Alam has worked hard to change the way that rich world publications deal with events in Bangladesh and the majority world generally, although not always yet with great success. From 1983 the political events in his country turned him to documenting the political movement against the military rule of General Ershad which lasted, with minor changes until 1991. During the later years of that period there was increasing disorder and a ban on reporting pro-democracy activities – which newspapers responded to by ceasing publication. During this time Alam kept sending out pictures of the political events to news organisations around the world – who ignored them , as to them it wasn’t news. The only time the world press took any interest in Bangladesh was at times of natural disasters – cyclones and floods. (Presumably, though he didn’t say so, this became news because of the pressure from the major aid agencies, who avoid involvement in ‘political’ issues.)

Alam’s talk was entitled ‘When the lions find their storytellers‘, from the widespread African proverb “Until the lion has his own storyteller, the hunter will always have the best side of the story.” Whoever does not have a voice is almost always going to be the loser. His life’s work has been trying to tell the lions’ story and to teach the lions so they can tell their own story.

Drik Picture Agency has played an important part in this, and more recently has set up ‘Majority World‘, a platform set up to allow “indigenous photographers, photographic agencies and image collections from the majority world to gain fair access to global image markets” and to present image buyers with “the the wealth of fresh imagery and photographic talent emerging from the Majority World.”

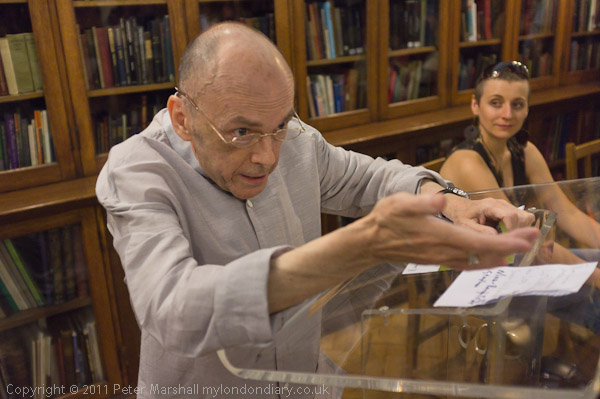

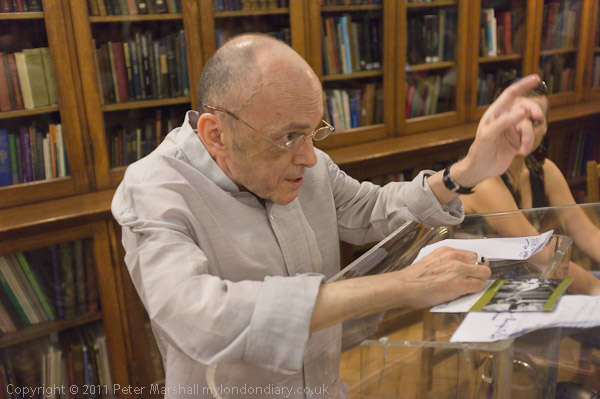

He ended his talk with a little about two of his heroes, and the final image was what is now perhaps his best-known photograph, possibly the last official portrait of Nelson Mandela. As always, Alam had a story to tell, of how he was held up travelling from Mexico to take it and thought he had missed his chance to take the picture, but hearing about his transport problem, Mandela actually rescheduled the sitting for two days later. The picture seemed to be a suitable backdrop against which to take his picture and I got out my Fuji X100 and took a few frames from my third row seat, some of which needed rather drastic cropping.

Questions at the end of the talk brought out some other vast aspects of his work that he had not included, including the work he and his fellow photographers have undertaken over the years on the vast environmental problems of his country, much of which is likely to disappear as global warming leads to sea level rise.

One questioner brought up the problem of the relationship between documentary and art photography, and of how Alam has managed to work so effectively across both spheres. It was during his answer that he removed the pair of ordinary inexpensive sandals he was as always wearing and held them up into the light, saying put them in a gallery with the right display and lighting and they would sell as a work of art for thirty or forty thousand pounds (I did think he might have to change his name to Tracey Emin as well) before putting them back on his feet and saying these are now just sandals again. It was only a part of his response, but like much of his talk, one that promoted thought. He also talked about the Crossfire project on extra-judicial killings in Bangladesh which rather than attempting to look at these by documentary photographs of events he made large format colour images of the places where the killings had taken place, exhibiting them together with the facts about the events in what he called “A quiet metaphor for the screaming truth” – and which was closed and barricaded by armed police – but as I also mentioned here was opened in the road outside the gallery.

It was a talk that was full of hope and inspiration, but one that also left me with something of a feeling of despair for the situation of photography in my own country. In Bangladesh things seem much starker and the struggles and possibilities more obvious. Here photography often seems strangled, choked by the money and prejudices of the art world, distorted by academia. We’ve seen the abandonment of our major documentary resource, Side Gallery, by the Arts Council and the continued side-lining of our most democratic photography festival, the East London Photomonth, by the photographic establishment.

Shahidul Alam’s first solo retrospective in the UK, ‘My Journey as Witness‘ opens at Tristan Hoares gallery in the Wilmotte Gallery at Lichfield Studios, 133 Oxford Gardens, London W10 6NE on 6th October, and runs until 18 November 2011, with a book of the same title being launched the in the UK on October 10 by Skira, Milan. Copies are actually already on sale and I took a short look at it at the National Geographic Store. It is certainly a tribute to Alam that the first volume in what Skira intend to be a multi-volume series on the arts of Bangladesh is devoted to him and to photography. The book has an introduction by Sebastião Salgado and preface by Raghu Rai.

Also here on >Re:PHOTO you can read about two earlier exhibitions curated by Alam, in ‘Bangladesh 1971‘ at Autograph and ‘Where Three Dreams Cross’ at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2010. Writing about World Photography Day earlier this year (a piece prompted by a post on Shahidul News) I concluded:

Photography may have started in France (and England) and perhaps came of age in the twentieth century in Europe and the USA. But now much of the more interesting work is happening elsewhere.

It seems a good way to end this over-long piece too.