In August I went to two events organised because of the shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and the military-style response by the US authorities to the protests there that followed his murder.

Although the scale of that repression is something we haven’t yet seen in the UK, I’m writing this a couple of months later just before I go out to photograph the annual march by the United Families and Friends Campaign who have a long list of 3,180 individuals who have died in state custody since 1969; at the bottom it states ‘Too many have died in questionable circumstances. Too many killed unlawfully … and pitifully too few held to account for the deaths of those we name here.’ Also published today, accompanied by one of my photographs (and another by Matthew David), is the closing speech by writer and activist Kojo Kyerewaa from last month’s annual conference of the London Campaign Against Police & State Violence.

And another reminder that similar things happen here in London were the speeches at the first of the events I covered of Carole Duggan, the aunt of Mark Duggan, unarmed and surrendering to police when they shot him, and at the second by Marcia Rigg, the sister of Sean Rigg, killed inside Brixton Police station in August 2008.

The two events, both at the US Embassy in Grosvenor Square, were organised by different groups, the first by ‘London Black Revs‘, the Revs being short for revolutionaries, rather than men of the cloth, and the second, ten days later, by a wider range of organisations, led by Unite Against Fascism, and including the United Friends and Family Campaign as well as trade unions and other campaigns.

Prominent at the first event were the family of Mark Duggan, and in particular his aunt Carole Duggan, who spoke eloquently and at some length drawing out the parallels between his death and that of Michael Brown. Both were black, both were unarmed, both had raised their hands in surrender when they were shot by police. And both deaths were followed by a response from their communities that were turned to violence by police responses and followed by panic reactions by politicians. Both brought into swing a huge media effort by the authorities feeding lies and covering up the truth about what happened, and in various ways conspiring to deny justice.

A torrential rainstorm added to the photographic problems of the event, though also providing some opportunities. At first I sheltered – along with many of those present – under the trees along the edge of the park facing the embassy, but soon the rain coming through and under their dense leafy canopy was too much, and I had to put my head down and dash for the cover of the broad concrete overhang of one of the embassy lodges with those shown in the picture above. It’s perhaps unfortunate that this picture suggests a rather smaller gathering, with others like me sheltering under the trees, under the canopy of the left-hand lodge and a few standing under umbrellas out of view.

Although it does show the rain, I don’t think any of my pictures give a real impression of just how heavy it was, a photographic problem for which I have no solution. Using flash certainly doesn’t work, though the light had sunk considerably and it would have been useful on this account, but it lights up every raindrop, with those close to the lens appearing over-large and out of focus and of course brighter. An effect well exploited by Martin Parr in his 1982 book ‘Bad Weather‘, I think the only one of his books I own that I actually paid my own money for, but not something that generally appeals to me or to editors. There are pictures in there by Martin that mean none of us should ever feel the need to do the same again.

My damp dash did get me closer to the speakers, and I was able to photograph them from the dry as they, standing a few yards out in the open and holding an umbrella as well as a megaphone, were still getting rather wet. Although an umbrella stops most of the rain, with heavy driving rain a fine spray passes through and slowly soaks.

Eventually the rain did slacken and stop, and photographers and some of the people came out from under the canopies, giving more varied opportunities for photography. We were a little too close to the embassy for many pictures to include the US Eagle and flag was too sodden to fly, but there was a small plaque on the gates that I could include in a few images, though it meant stopping down the lens to a rather smaller aperture than I would normally use to get sufficient depth of field.

Fortunately it had got a lot brighter – the sun was out and causing some contrast problems. For the man speaking under the umbrella I had been working at 1/100s f5 (ISO 800) with the 18-105DX lens at 52mm (78mm equiv), while at the same ISO the exposure for those holding the ‘London to #ferguson’ posters I needed 1/500 f13 – at 66mm (99mm equiv.) I think that means a difference of over 5 stops, though it’s too early to really do the maths as I write.

At the end of the protest, those present decided they would like a group photo in front of the embassy. I’m never a fan of group photos (except perhaps the Brown sisters) and certainly not for groups of this size. Photography always works best (or certainly almost always) on a more intimate scale – if Hill and Adamson had been able to photograph all 457 of the ministers at the First General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland we would have just had one rather boring photograph rather than the earliest (and still one of the best) great collection of photographic portraits.

And the picture the activists wanted did rather remind me of that ‘Disruption Picture’, except there were rather fewer people and they were far less well organised. It too was impossible to take as the area in front of the large group was crowded with people with cameras and phones in the way. As usual people there were people shouting and gesturing ‘Let’s move back, move back‘ but while photographers might reluctantly respond if they see any chance that others will do so rather than just as usual move in front of them, holding up a phone to take a picture (or worse video) seems to render people terminally deaf and impervious to their surroundings. It really isn’t a licence to walk in front of photographers.

The only way I could manage to get everyone in – if not very satisfactorily – was by working close to one end of the wide spread group with the 16mm fisheye – and then converting the image to a cylindrical perspective to lose some of the fisheye effect. But even with the fisheye I could not get far enough back to take the picture from the centre of the group without people with phones and cameras being in the way.

The second protest, ten days later, was held in the evening, and towards the north end of the embassy frontage, in front of the rather dreary statue of Eisenhower. The organisers had produced a graphic poster, two black hands with the message ‘Hands UP! Don’t Shoot!‘ which dominates perhaps rather too many of my pictures, though it was unmissable.

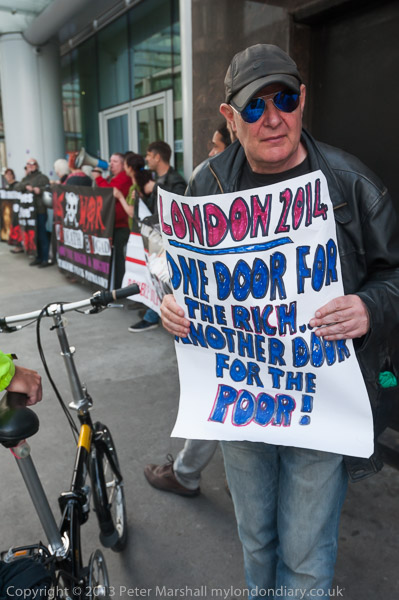

Weymann Bennett is someone I find it hard to take a bad picture of, and there were others speaking that I also like working with, including Marcia Rigg and Zita Holborne, who had brought along a couple of placards of her own.

You can see her other one in another image of her, standing together with Marcia Rigg which is together with a larger selection of pictures from both protests – and text about them – on My London Diary:

Solidarity with Ferguson

Hands Up! Against racist Police Shootings

No Justice, No Peace!