A few minutes on Wikipedia convinces me that April 23 has more than its share of famous births, deathas and commemorations of which the best known here is of the man the Eastern Orthodox call “Holy Glorious Great-martyr and Victory-bearer and Wonderworker George“, a Palestinian (or Turk) of Greek parentage and a Roman soldier – if he actually existed. Certainly the dragon didn’t, and was not involved in the legend that made him a saint, in which, undoubtedly like some Christians of the era, he was tortured at length before being beheaded for refusing to convert to the Roman gods following an edict by Emperor Diocletian in AD 303 which led to three years of such persecution, though applied with differing severity across the Roman Empire.

April 23 is a day George shares with a number of other saints, with Wikipaedia listing around a dozen for the Eastern Orthodox, including George’s mother, two soldiers converted by witnessing George’s martyrdom and the wife of Diocletian, as well as another 14 pre-schism Western Saints, post-schism Orthodox saints, new martyrs and confessors (though due to our change to the Gregorian calendar they celebrate these April 23 events on our May 6th.) In the West, George shares his feast day with Adalbert of Prague and Gerard of Toul, while both the Evangelical Lutherans and Episcopalians in the USA commemorate the life of Japanese Christian pacifist, reformer and labour activist Toyohiko Kagawa (1888-1960) which seems to me admirable. It’s a shame we’ve never heard of him here.

Shakespeare was probably born on April 23 1564, and certainly died on April 23 1616, giving us another reason to commemorate – and UNESCO chose April 23 as UN English Language Day, (one of six promoting its official working languages,) for that reason. It’s also UNESCO World Book Day, though in the UK we celebrate this on on the first Thursday in March instead, as April 23 is often in the Easter school holidays.

In England, St George’s Day once ranked with Christmas as a major celebration, an occasion for feasting and drinking, but its celebration became less important after the union with Scotland, and had almost disappeared in the last century. One or two people still wore a red rose, and some official buildings flew a flag, though usually the Union Flag rather than the English flag of St George. The day never became a bank holiday, partly because of its closeness to Easter (and the Church of England even moves his feast day when it gets too close to Easter, moving it from April 23 to the Monday following the Second Sunday of Easter.)

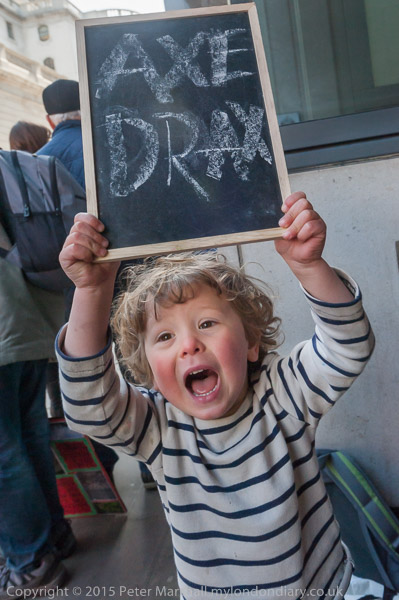

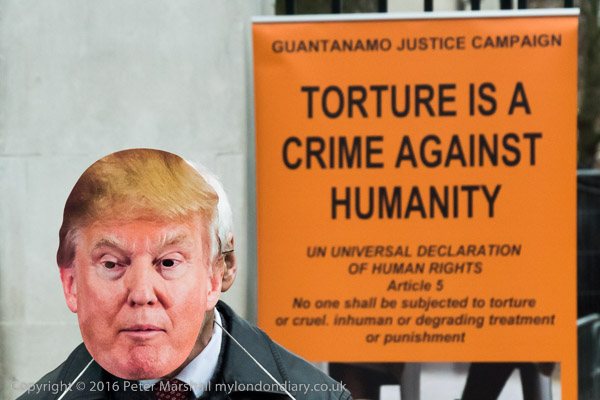

Back in the last century, even English sport teams and their supporters would often use the Union Flag rather than the English St George Flag, but it was sport and particularly football that led to a resurgence for the red cross on white, and pubs showing England games at the World Cup on TV that led to its proliferation across the land. It became associated with football supporters, and with the largely right wing hooligans involved in football violence who dominated many ultra-nationalist groups, often styling themselves as patriots, and looking back to a mythical past of an all-white England ruling an empire around the world, or even launching crusades against the infidel foreigners.

A strange alliance between these ‘patriots’ and others who have tried to reclaim the English flag from the bigots has led to an increase in official commemoration of St George’s Day this century, which has involved groups including the BBC, English Heritage and London Mayor Boris Johnson, as well as some churches, and it’s a mixture that has been reflected in my photographs of the day over the years.

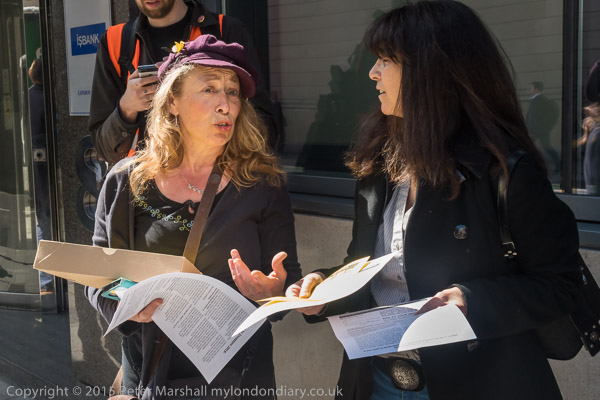

In 2016, St George’s Day actually fell on a Saturday, and I expected to see more activity than in other years, but was in the end rather disappointed. The Mayor’s day of events in Trafalgar Square seemed rather lacking in spirit, and all more organised events by ‘patriots’ in the London Area seem to have evaporated, perhaps because of increased militancy by anti-fascist groups. I paid a brief visit to Trafalgar Square, but found little to photograph – perhaps things got better later in the day, but the few pictures I’ve seen by others don’t encourage that thought.

South of the river in Southwark things were a little better with a festival ‘A Quest for Community’ with the aim of ‘Taming the dragon of difference’ involving a St George’s Day procession from the Roman Catholic Cathedral of St George to the Church of England St George the Martyr in Borough High Street. As well as St George, Diocletian and his daughter, a sooth-sayer and of course a dragon, it also included drummers and the Mayor of Southwark, to whom I was pleased to be able to point out a blue plaque and tell her a little about one of the Borough’s more famous son’s, photographer Bert Hardy, who grew up in ‘The Priory’ which was on our route.

She had been unaware that one of Picture Post’s best-known photographers and a pioneer in using 35mm in press photography had come from her patch – and never really left it, though advertising brought him enough money to buy and live in Chartlands Farm, Limpsfield Chart near Oxted. And about how his powerful photography had powered the textbook example of an unsuccessful advertising campaign, ‘You’re never alone with a Strand’ along with an outstanding ‘noir’ TV ad shot by Carol Reed with music by Cliff Adams that would have topped the charts had the BBC not banned it for advertising cigarettes. Even at 3s2d for 20, nobody wanted to be seen as lonely enough to buy them.

The procession ran late, and I didn’t have time to watch more than a few minutes of the play that followed, and missed the free pint that was waiting for me in the City where Leadenhall Market was also celebrating our patron saint. Instead I met with friends at the Old Kings Head in Kings Head Yard just off Borough high St, a welcome survival of a traditional English pub – and where better to meet not just one St George, but two, the second accompanied by his very own dragon.

I forget why we left. Perhaps it was the thought of a good dinner waiting for me at home, but I stopped for a minute or so in the yard outside for a last picture of St George with his dragon holding his own and George’s pint in the alley outside, a rather different and very English version of the legend, and my favourite picture from a long day.

More at:

St George in Southwark Procession

St Georges Day in London