For images by Rogovin, open a new window on the Rogovin website while reading this essay.

New York Origins

Milton Rogovin‘s parents, Jacob and Dora, were Lithuanian Jewish immigrants; Jacob had arrived in New York in 1904 and Dora came the following year with their year old baby Sam, and they set up a shop selling household goods on Park Avenue in New York’s Harlem. Their second son was born in 1907, followed in 1909 by Milton. His first language and that of his family was Yiddish.

Business started to get tough after the First World War ended in 1918, and in 1920 the family and shop moved to Bay Ridge in Brooklyn, but Milton travelled in to Manhattan to attend Stuyvesant High School. From there he went on to Columbia University where he qualified as an optometrist in 1931.

By then the depression had hit, the family store had gone bust, and his father died of a heart attack four months before he graduated. Work as an optometrist in New York was hard to find and sporadic. In 1938 he moved to Buffalo to take a job there where there was more opportunity.

Politicisation

The depression and his own experiences, particularly the failure of the shop and his father’s death made him become politically active, and he helped to set up the Optical Workers Union in New York City. He continued his union activities after moving to Buffalo, losing his job there in 1939 when he picketed two of his boss’s offices.

He had met Anne Snetsky (later Setters) at a wedding in Buffalo in 1938, where they argued about the Spanish Civil War – he was highly concerned while she was then indifferent to the cause – and fell in love. They were to remain life-long lovers and comrades until her death in 2003.

With Anne’s encouragement and the support of the union, he decided to set up in practice as an optometrist on his own, on the edge of Buffalo’s deprived working-class Italian Lower West Side.

War Years

Anne and he got married in 1942, which was also the year Rogovin bought his first camera. Later in the year he volunteered to serve in the US armed forces, training as an X-ray technician before being assigned to serve as an optometrist. During his training he entered and won a photo contest at the training school with a picture of a waterfall taken on his new camera.

In 1944 he was posted to a hospital in Cirencester in the west of England, until the end of the war in Europe.

Back In Buffalo

After war service, he returned to Buffalo, where his brother (also an optometrist) had been keeping the practice running, and they worked as partners. He continued his political activities, becoming the librarian for the local communist party, as well as being active in the union, taking part in encouraging black voters to register and other political campaigns.

Mexico

Rogovin and Anne made their first visit to Mexico in 1953, where they met a number of left-wing Mexican artists and then and in subsequent visits over the next four years he made a number of photographs there.

He was by this time developing a greater interest in photography, showing pictures in the annual Western New York Exhibition at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1954 and 1958.

Red Scare: “The Top Red in Buffalo”

Cold-war hysteria in America was growing, and in 1957 Rogovin was summoned to appear before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. Rogovin invoked his constitutional right to refuse to testify rather than cooperate in any way, but became the subject of various newspaper headlines which labelled him as ‘Buffalo’s Top Red.’

In the following months his business fell off dramatically; some who thought of themselves as loyal Americans wanted nothing to do with ‘Commies’, while others felt that they too might suffer from similar smears if they continued to associate with him.

Many photographers and other artists also suffered from McCarthyism. The New York Photo League, the most important and vital photographic organisation of the era – one that changed the history of photography and had many leading photographers as members (and to their credit others joined to try and protect it after it had been named) – was forced to close. Paul Strand chose to leave America and live in France to avoid the persecution. Any American who dreamed there could be a better and more equal future was open to attack.

Store Front Churches

Rogovin was left with time on his hands as the business collapsed. William Tallmadge, a friend and professor of music at Buffalo State University, was recording music at one of Buffalo’s Afro-American Holiness Churches and invited him to come along and photograph.

The experience decided him to dedicate his life to photography. Progressive political activities had become virtually impossible in Buffalo and he felt his “voice was essentially silenced, so I decided to speak out through photographs.”

After working with Tallmadge for three months, he continued to photograph in Afro-American churches in Buffalo for the next three years, learning the skills that he needed. He went on a two week workshop with Minor White, who showed him how to use the bare-bulb flash technique that he continued to work with for the rest of his career, and worked out how to photograph black faces in a way that achieved proper gradation with their darker skin tones.

White also gave him advice on shutter speeds, suggesting that rather than use 1/125th which had the effect of freezing the movement of his subjects, he should use a slower speed, perhaps 1/25th, which would give a slightly more dynamic quality where there was some movement.

His approach when photographing people was simple and straightforward. He would ask permission to take their picture, set up his camera on its tripod and let them decide how to pose. The only thing he would ask them was to look at the camera – he liked to see their eyes – as was perhaps natural for an optometrist. The camera meets the gaze of the subjects, giving his work a powerful directness.

Minor White was a great supporter of his work, and published pictures from the project in his magazine, Aperture, getting W E B Du Bois, one of the founders of the NAACP (National Association of the Advancement of Colored People) to write an introduction.

Family of Miners

Rogovin was not making money from his pictures at this time. Fortunately Anne was still able to carry on with her teaching in special education and support the family and his work, as well as helping him in developing his projects.

In 1962, they read about the problems in the coal industry and in particular for Appalachian miners, with declining production as the car industry leading to lower demand for coal. As well as increasing unemployment there were also the health problems faced from working under appalling, dusty conditions underground, with most or all eventually succumbing to silicosis.

A letter to the mineworkers union president got them an introduction to the union office in West Virginia, and during Anne’s summer break they travelled there to see and photograph the workers. They were to return for the next eight summers to continue the work.

In 1981 he began a larger project which he called ‘Family of Miners’, starting again in the Appalachians. The following year there was a show of his work on the store front churches and working people in Paris, and he came and photographed miners in the north of France, then in 1983, support from the Scottish miners union enabled him to photograph miners in Scotland.

In 1983, he received the W Eugene Smith Award for Humanistic Photography and was able to extend his work on miners to other countries, eventually including China, Cuba, Germany, Mexico, Spain and Zimbabwe

Neruda and Chile

On 1967, Rogovin sent a letter to the great Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda, requesting his help in producing a series of photographs of the people and the country with Neruda’s writing. Some of the pictures were published in the Czech Revue Fotografie in 1976 later the project was published as ‘Windows that Open Inward‘ including poems by Neruda.

Lower West Side

By 1970, Rogovin was deliberately cutting down his remaining work as an optimetrist to spend more time on photography. However it was not until many years later, around 1978, that he was able – with family support and his wife’s income – to give this up to be full time as a photographer.

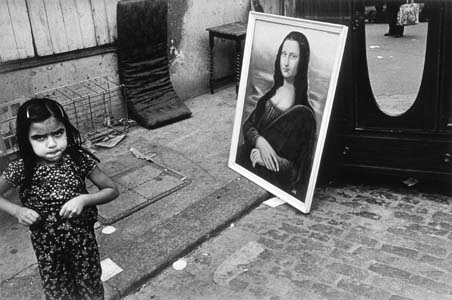

His next major project began in 1972, when he decided to document the Lower West Side. The Italian population there when he moved to Buffalo had moved out to wealthier areas, and had been replaced by Puerto Rican and African-Americans. It was now an area with high levels of crime, drugs, alcoholism, prostitution and high unemployment.

At first people there were very suspicious of a white guy with a camera, regarding him as a spy sent by the police or other authorities. With the help of Anne, he slowly get to know people and gain their trust, enabling him to photograph them in their homes as well as in public.

When he took his Hasselblad and set it up on a tripod, he noticed that people came up to him and asked him how much it had cost. He took the hint and decided it would be more sensible to use his old Rolleiflex instead – and it was his preferred camera from then on, used for most of his best pictures.

The Rolleiflex – like the Hasselblad – has a focussing screen on the top of the camera, requiring the photographer to bow his head to look down at it. This reverent attitude towards the sitter contrasts with the more aggresive direct view, aiming at the person with an eye-level viewfinder. It reflected his attitude to those he photographed.

Three years of work in the Lower West side led to his first major exhibition, at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo. He organised a smaller show in the Lower West Side itself with buses to the gallery so that those he had photographed and their friends would see the work.

He returned to photograph there in 1984-6, at Anne’s suggestion producing ‘Lower West Side Revisted‘ which pairs these pictures with the work a dozen or so years earlier in diptychs. He managed to locate over a hundred people he had photographed previously – and found many had the pictures he had made hanging proudly on their walls.

Following his recovery from surgery for a heart problem and prostate cancer, again prompted by his wife he returned again in 1992-4, again photographing the same people thus producing some outstanding triptychs taken over a 20 year period, showing them at radically different stages in their lives. These produced the book ‘Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited‘ (1994.)

By 1997, cataracts in both eyes and fading sight forced Rogovin to sell his camera and shut up his darkroom. But being unable to photograph was too frustrating and he had surgery in 1999, which restored his vision, and he bought back his camera.

In 2000, with Anne and broadcaster Dave Isay, he returned to photograph in the Lower West Side for a fourth time. They managed to find 18 of his original subjects and photograph them to produce a series of ‘Quartets’. Isay had worked with photographer Harvey Wang, who produced the award-winning documentary short film ‘Milton Rogovin, The Forgotten Ones‘ (2003.)

Workers

In 1976, inspired by a Bertolt Brecht poem, ‘A Worker Reads History‘ he began to photograph workers at the steel mills and car factories around Buffalo.

A picture of a steel worker and child feeding ducks outside their home published in the Illinois Historical Society journal led him to extend his work. When he had photographed someone at work, he would go back with a print and a request to photograph them at home with their families. His workers are not just workers, not just a small cog in the machine of production, but people, individuals with their own lives outside of work.

In 1987, he returned to photograph these people again, now out of work, as steel production had ended in the area.

In 1993, his book ‘Portraits in Steel‘ was published, with interviews of the subjects by Michael Frisch.

Working Methods

Working with 120 roll film, Rogovin could make 12 images on a roll, and to keep costs down he usually fitted three or four people or groups onto each roll, taking only 3 or 4 frames for each of them.

He did all his own darkroom work, developing the film and them contact printing it to choose which of the frames to enlarge. The Rolleiflex (and Hasselblad) produce 6×6 cm negatives (actually around 56mmx56mm) making the contacts easy to assess. Normally he would chose at least one image of each person and print it carefully, dodging and burning as required to bring out the most from the negative, to make sure that he had a good picture to give to the subject.

The bare bulb technique is a good method of getting fairly even light in small rooms. As its name suggests, it uses a bulb holder with a bulb but no reflector, so that light is given out in all directions more or less evenly. Shooting as he usually did in small rooms, this produced in a lot of light bouncing from walls and ceilings as well as some direct illumination.

Special flash guns or slaves can be bought for bare bulb use, or you can get bare bulb effects from an ordinary flashgun by using an attachment – a large translucent bulb on the front of the flash. You do however need a fairly powerful flash as the light, being spread out is considerably less intense than with a normal directional flash.

Rogovin worked almost entirely in black and white. He decided that colour was a distraction that took people’s attention away from the subject and into thinking about the colour of the clothes or surrounding objects.

Colour would of course have added considerably to his costs and to the complexity of the processing and printing. Black and white is very much more straightforward to process and print yourself, while colour is generally best handled by machine rather than hand processing.

Influences on his Work

Although Rogovin was aware of documentary photography and was a friend of Paul Strand, as well as having respect for the work of photographers such as Lewis Hine, Walker Evans and Margaret Bourke-White, he has said that his major influences came not from photography but painting, and in particular the work of Goya and Kâthe Kollwitz.

It is perhaps hard to understand this, looking at the very photographic quality of his work. Of course the paintings may interest him more and inspire him to get out an make images, but the forms that these take are rather more clearly based on the photographic sources.

One particular film by Luis Bunuel, ‘Los Olvidados‘ (1950) did have an important impact, and is reflected not just in the title of his book ‘The Forgotten Ones’ (he liked it so much that he actually used the title for two books, the first in 1985, and then in 2003), but in a devotion throughout his working life as a photographer to photograph ordinary people rather than the rich and famous. In its concern for ordinary people and their often forgotten lives his work obviously resembles Bunuel’s film, but it lacks the surreal symbolism which is central to Bunuel’s vision.

Peter Marshall, 2007

Other web links on Milton Rogovin, some of which provided information for this feature:

Milton Rogovin web site

Library of Congress: Milton Rogovin

Luminous Lint – Milton Rogovin

N Y Times A Sympathetic Lens on Ordinary People

NPR: Milton Rogovin

Afterimage: Robert Hirsch Interview with Milton Rogovin

The Forgotten Ones (book – with pictures on line