Its nice to know, thanks to the review article on ultra wide-angles in the April issue of British Journal of Photography, that “Nikon’s newly announced 16-35mm f4 VR (will be) available later in the year” when I’ve been using it for well over a month. The first shipment to the UK arrived shortly before the end of February, and mine was on my camera the following working day.

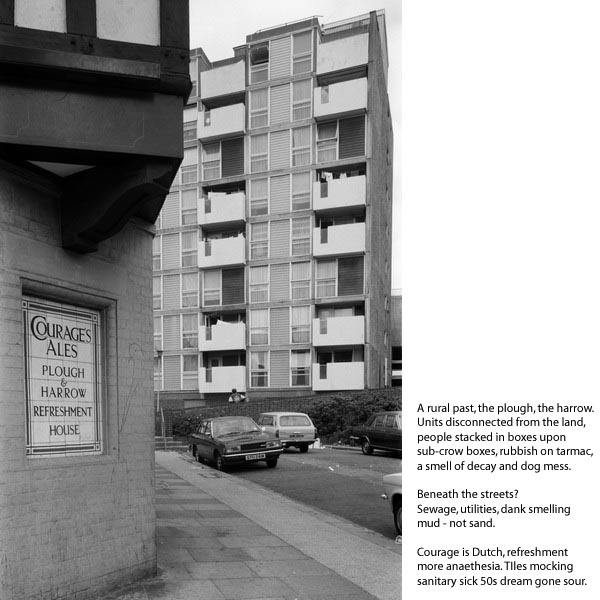

One of thousands I’ve taken with the Nikon 16-35mm f4 VR: 16mm f5.6

It was the lens I’d been waiting for since I bought a Nikon FX body. I’d tried the Nikon 14-24 f2.8 (described in the BJP as setting a new standard for the class) but had not been impressed; the few test shots I took with one were fine, but convinced me that this was an impractical lens to work with, largely because of its bulging and unprotectable front element, but in any case it just did not feel right on the camera. In any case I already had a Sigma 12-24 that covered full frame, and although it wasn’t as fast or quite as sharp as the Nikon, did a reasonable job, but too often I was finding that I had to switch lenses as 24mm wasn’t quite long enough. Looking at the various focal lengths that I took pictures at when using this lens I could also see that there were relatively few good images made at wider than 16mm – and usually images that I tried just looked too wide.

I’d looked long and hard at the older 16-35mm but wasn’t too happy with the performance, particularly at the price, of a lens that was really designed for film. So when the new 16-35mm was announced I wanted one. Unlike a loud chorus on the web I wasn’t worried by a maximum aperture of “only” f4 – with the kind of high ISO performance available on the D700 (or D3) the loss of one stop over f2.8 seemed a minor detail. And although I’d have preferred a smaller, lighter lens it was within the limits I was prepared to go to for improved performance. My only sticking point was the price, but in the end I decided it was worth the £999 which was the cheapest I could find it at at UK dealer, a decent saving on the recommended price.

I don’t review lenses, I use them. I’ve been using the 16-35mm for 5 weeks, quite a few thousand exposures, and haven’t been able to fault it. Focus is fast (so fast and quiet I’ve sometimes been reluctant to believe it has focussed.) VR would not be high on my list of priorities for any wide-angle, and I’m frankly unsure whether or not it has helped at all in any of my images, though I’ve left it switched on all the time. When I’ve made unsharp images, its either because I’ve focussed in the wrong place or someone has moved too fast for the shutter speed I’ve been using, neither the fault of the lens.

I’ve had a lot of chances to use it in the rain. It’s coped without problems and seems well protected at least if you don’t leave it out in the rain too long and keep wiping it. The lens hood is as you might expect not a lot of use for anything, other than a little protection. I do wish Nikon would make lens hoods rather stronger and with a better bayonet fitting – like all the other Nikon ones I’ve used this one falls off occasionally. I’m tempted to glue it in place, but it is occasionally handy to reverse it for storage.

Unlike many lenses it is truly an f4 lens, usable wide open. f4 is wide enough to give a reasonably bright viewfinder image too. I’m sure lens tests would show it improves on stopping down, but I don’t think it is noticeable in the pictures.

As for the image quality, generally I’ve been impressed. Relatively low distortion for the focal length – I don’t think I’ve felt moved to correct anything I’ve taken with it. It would be a problem with architectural subjects at around 20mm and less. In a standard “brick wall” image at 16mm focal length I have 23 courses visible in the centre of the image and between 24.5 and 25 at the edges. At 20mm I think there is probably very slight barrel still, but it really is hard to decide, and it seems distortion free at longer focal lengths.

Here are my comments on sharpness in some simple photographic tests photographing the house across the road:

16mm At f4 sharp centre, slightly soft at corners, small amount CA largely removed by R/C-18 B/Y+13 in Lightroom. At f5.6 corners were sharp too. Viewed at normal size (300 dpi) results at f4 were acceptable across the frame

24mm At f4 corners more or less as sharp as centre, very slight CA red green and blue yellow, largely removed by R/C-13 B/Y+8 in Lightroom.

35mm At f4 sharp across entire frame, very slight CA largely removed by R/C-13 B/Y-10 in Lightroom.

Another point I like about this lens is that it doesn’t change at all in size as you zoom or focus – all movement is internal. I’m not sure why this seems such a good thing – though of course it makes the weather-sealing much more practicable, and it somehow seems less fuss. It gives the lens quite a different feel from say the DX Nikon 18-200mm which of course has a much larger zoom range, but does sometimes make me feel more like I’m playing a trombone that taking photographs.

So I can recommend the Nikon 16-35 without hesitation if you are shooting on FX format. I’ve not tried it on the D300, but imagine it would be fine, giving the equivalent of a 24-52mm zoom, a high quality general purpose lens. I’m hoping soon to be able to pair the 16-35 on FX with the 24-70mm Sigma f2.8 on the DX D300, where it would be the equivalent of a 36-105mm, the two together covering most of my needs. Add the lightweight Sigma 55-200mm I have for when I need something really long and it would be a pretty comprehensive outfit.

Unfortunately I don’t yet have the 24-70 back from Sigma where I sent it for repair almost 2 months ago. When I first got it I thought it was another great lens (at least when stopped down to f4; wide open at f2.8 it could look a little soft) but after a few months it started to give problems and something inside was obviously loose, so I sent it back to Sigma for service under warranty. They stopped it making the nasty grinding sounds but optically something was still very wrong so it quickly went back to them. Today I phoned them again to hear that they had to send it back to Japan as they couldn’t get it working properly (and apparently I should have been sent a letter to tell me this.) The good news is that as Japan can’t repair it either they are sending me a replacement lens – which should arrive in a week or so. I hope that this will be a happy ending to a rather long story.

Nikon D700& Sigma 24-70mm f2.8, 24mm

Here’s a picture I took with the Sigma when it was working properly last July. The pigeon was released by the priest at the right and flew directly at me and much to my surprise the camera and lens had kept it in focus, although it was extremely close to me and the flash, which gave a sharp image as well as the slight blur of the ambient exposure.