I decided to try out my new Fuji X cameras at the CND Aldermaston protest on April Fool’s Day – Nuclear Fool’s Day – Scrap Trident – for a couple of reasons. First was that I was going to cycle some of the way to the protest, and my bag full of Nikon gear is just a bit too big and heavy to be easily carried on my bike. My normal camera bag won’t fit into a pannier on the bike, and cycling more than a short distance with the strap across my chest gets difficult. I can put the gear in a back pack, but I find a pain working out of that.

The two Fuji cameras – the X Pro1 I got in a swap with a mate and the EX1 I bought together with the 16-55mm lens – fit into a much smaller (and lighter) bag, along with all the lenses I need and it will slip into a pannier for longer rides. So I hope to be able to use the Fujis when I want to cycle, and also, because of the much lighter weight, on days when I’m going to be carrying gear for a long time or distance.

I’d first tried them for real on Good Friday and had got on quite well, though there were just a few problems compared to the Nikons. I’d begun to get used to some of their oddities and problems and felt I could probably handle the Nuclear Fool’s Day – Scrap Trident event.

One big problem is lenses. I’ve two camera bodies but only one Fuji lens, the 18-55 zoom. But I do have adapters that enable me to use Leica M and Nikon lenses on the Fuji cameras, though only with manual focus and manual aperture setting – though auto exposure works in aperture priority mode. The 18-55mm is neither very long or very wide, a 27-78mm equivalent. Fuji are promising a 10-24mm f/4m and a 55-200mm f/3.5-4.8 in the relatively near future that will together cover most of the range, but until they are available it isn’t a real system.

So for the moment I’m relying on a few other lenses to fill the gaps. At the wide end is one I’ll continue to use, the Nikon 10mm f2.8 DX semi-fisheye, and another I’ll perhaps ditch, the 15mm Voigtlander, which becomes a useful 23mm equivalent – and is quite a nice lens when you want a really compact camera. And at the long end, the 90mm f2.8 Leica is a nicely fast 135mm equivalent.

For the Aldermaston protest, although I took several other lenses, I worked with two only, the Fuji 18-55 on the X Pro1 and the Voigtlander 15mm on the X-E1. It might well have been better the other way round, but the 15mm is too wide for the optical viewfinder on the X Pro1

Of the two bodies, the X-E1 is I think the better camera, with an almost decent electronic viewfinder, a slightly simpler interface and less tendency to doze off when you want to use it. The viewfinder isn’t perfect, and often only just good enough for you to know where you are pointing the camera rather than the nuances of the scene, but it responds fairly quickly and I seldom missed an image with this body.

The optical viewfinder on the X Pro1 is great, but sometimes the white line frame was very slow to appear, and I did miss some pictures. It seems to work better on electronic viewfinder, but this is rather cruder than that on the X-E1. It is possible to set the frame lines on on the optical viewfinder for non-Fuji lenses, but doing this slows down lens changes, while the electronic viewfinder of course automatically adjusts.

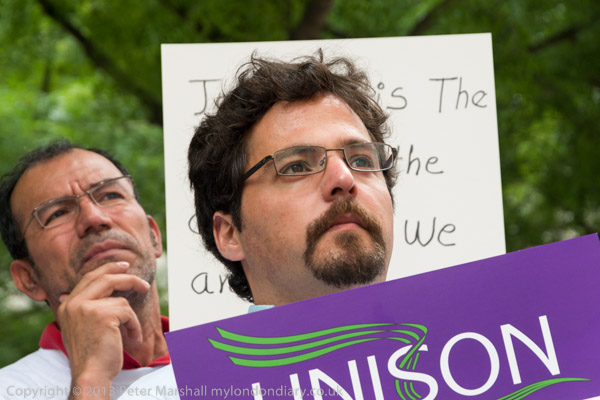

The one problem I had using the electronic viewfinder on the X Pro1 was in photographing people, when I couldn’t always see their eyes clearly enough to ensure they were open and to judge their expressions. I found myself having to watch them with my other eye and use the viewfinder simply for framing – you can’t really see the image clearly enough to assess it as you would in an optical viewfinder.

No problems with this speaker who keeps his eyes wide open, but those who blink a lot are trickier

I do have some problems with the position of some of the buttons on the camera. I constantly press the Macro button on by mistake – which slows down focussing on distant objects, and it is far too easy to move the exposure compensation dial. The Q button also is annoyingly easy to press by mistake.

The 15mm Voigtlander is small and light and virtually distortion-free

When changing to a non-Fuji lens you lose almost all of the automatic functions, though the camera will adjust the shutter speed to give correct auto-exposure. But you have to set the aperture manually, and also to focus. With wide-angles it is usually easiest simply to focus by the scale on the lens, but you can also press the main control dial and get an enlarged digital view of the centre of the frame whether using optical or digital viewfinders with the camera in manual focus mode. This is the only way to get precise focus with longer focal lengths such as the 90mm.

The Nikon 10.5mm also requires to be focussed in this manner, as the Nikon mount I have doesn’t give correct infinity focus. Perhaps a more expensive Nikon mount might do better. It is rather an annoying fault which considerably slows down use of this lens. With lenses such as this that have no aperture ring, the adapter has to have one built in, which has to be set by guess work – I focus at full aperture, then watch the change in shutter speed as I turn the ring to guess the aperture I have set. But although I took the 10.5 Nikon along – though petite by Nikon standards it was much the heaviest lens in my bag – I didn’t find a situation where I needed it at Aldermaston.

I carefully tested all the Leica fit lenses I own with the Fuji cameras before taking pictures and you can read more about this in Hogarth and Fuji. In that piece I noticed no shutter lag with the Fuji X Pro1, but with more mobile subjects I did begin to notice the sometimes slow focussing with the Fuji lens. There still seemed to be some lag when I’d half-pressed the shutter to set focus before releasing the shutter.

Other than this and the occasional sleep mode that the X Pro1 indulges in, I had few problems. I did need to change batteries after around 300 pictures. The results technically are on the same level as I would get with the Nikons.

This wasn’t a fair comparison as I have only one Fuji lens, and had to use the Leica lenses in manual focus mode; things may change a little when the two promised Fuji zooms become available. It is also possible that Fuji can iron out some of the sulking with a firmware upgrade. It’s a shame also that lens profiles are not available for the Fuji lens in Lightroom, though I didn’t see a need for any correction for this kind of work.

Although I’d love to be able to lighten the load on my shoulder when working, the Nikons are so much better at handling fast-moving situations that I’m unlikely to stop using them for most of my work. They focus faster, are immediately responsive (with a few minor niggles,) and the optical viewfinder is still so much clearer (and of course reacts at the speed of light) than even the X-E1 digital finder. The much longer battery life is also useful.

As well as the lighter weight and smaller size, the Fuji’s do have at least one other advantage, with I think slightly better colour, particularly in those pictures I’ve taken on other occasions in artificial light. I like working with the X Pro1’s optical viewfinder, being able to see clearly outside the frame line – something I can mimic by using the D800E in DX mode, but not quite as well. It is a great camera to work with when I have a little more time, and occasionally missing the exact moment isn’t critical.

More pictures on My London Diary: Nuclear Fool’s Day – Scrap Trident

________________________________________________________

My London Diary : Buildings of London : River Lea/Lee Valley : London’s Industrial Heritage

All photographs on this and my other sites, unless otherwise stated are by Peter Marshall and are available for reproduction or can be bought as prints.

To order prints or reproduce images

________________________________________________________