A Dear John letter by John Benton-Harris to a colleague about:

This is War & The Subject of War

at the Barbican Art Gallery (16 October – 25 January 2009)

Dear John,

It was nice running into you at the Barbican, and good to see that you are keeping well. It was also good that the Barbican has retained something of my improved thinking on exhibition design and traffic flow in that very peculiar and difficult space. For as you I am sure have noticed, this gallery resembles something more akin to the dining room of the TITANIC, then any appropriate space for hanging art. It was also swell to socialize with some of the artists who make up the gallerys hanging crew. I must tell you however that I was very disappointed with both the upstairs presentation – Robert Capas This is War (AKA – Endre Erno Friedmann) and a much smaller presentation by his non-notable girlfriend Gerda Taro (also previously named – Gerda Pohorylle). Anyway, looking around this presentation, I would be forgiven for thinking that these small, toneless, grubby un-spotted prints came out of that same long lost valise, which housed those negatives. It may have been sufficient to represent Gerda’s contribution to photography, but not Roberts, for this staging reveals more of the weaknesses of his seeing then its strengths. So if I were forced to come to a decision about Roberts ability based on this presentation of his work, he would fail spiritually, emotionally and intellectually. And about any question of him being an artist, he would fail there as well.

I realize these are harsh words, but looking at these repetitive rows of small, shapeless and thoughtless moments (although beautifully over matted, framed, lit, and presented) this poor limited selection tells me he was only physically present. And that, in my book, denies him the title of the greatest anything, for greatness is a privilege reserved for those who consistently find themselves in the right place at the right time, just for starters. These images for the most part have no real clear readable central drama, and no edge concern either, and both are required to make a message taut, to maximize viewer response, and to clarify ones intent, to go beyond showing that one was merely present. The majority of these out-takes from time suggest that most likely he was holding the camera away from his eye and possibly even above his head, while running. The bottom line, from this credible reading of them is that Robert failed to adhere to his first principal of seeing, which is, in his own words – “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.

This selection of weak, loose and wanting moments, taken from wherever Robert was, rather then from where he should have been, along with their tortuous repetition and unimaginative juxtapositionings further diminished by slow shutter speeds which resulted in camera shake. All taken together tells us looking at what we got away from the written blurb, that Robert was simply a very nervous adventurer, with poor technical skills, there for the buzz – and didnt even have the sense to keep his bit of skirt out of harms way.

So in order to reassure myself about him and his dedication, I needed to revisit my library to remind myself afresh that there was more to him then met my eye at the Barbican. Although there were those few classic historical moments in this poor portrait, such as Death of A Loyalist Soldier 1936 and D-Day Normandy Beachhead -1944, their shock was considerably lessened, indeed almost lost, among so many “SO WHAT” images, denying us his humanity or his reason for being a man at war.

This show also attempted to prove that Gerda Taro was Capa’s equal, or possible his superior, simply because her two rooms worth of shaky out-of-focus snaps that filled her viewfinder slightly better than those of Roberts on display. Hence Gerdas importance to photography (as seen by the Barbican and possibly ICP – the New York International Center of Photography – originator of this show) has more to do positive discrimination and a feminist agenda then it does with any sighted humanism or commitment to minded seeing.

I do hate it when market forces and distortions of this or any other kind, work to devalue this history. Its simply much too high a price to pay for her inclusion.

Returning to that Omaha Beach image of a soldier seeking protection behind tank traps from the onslaught of bullets and mortars ricocheting and exploding all around him in on that Normandy shoreline, littered with the floating dead, in the cold early morning light of the 6th of June 1944. This D-Day image was the image that started my modest print collection, back in 1961 although I had to part with it when hard times struck 33 years later. On a more pertinent and optimistic note, my print of this moment was given extended significance by it’s new custodian – Steven Spielberg, and its influence on him helped to create the opening sequences to his film “Saving Private Ryan”, so giving the world a greater dramatized reflection of the events of that horrific morning. To my mind, this was a price worth paying for my personal loss of this historic moment.

The title of this show was lifted from Davis Douglas Duncans Korean book, of the same name, published in the early 1950s. And unlike this show this was a presentation about several things, firstly one mans dedication to fallen colleagues, secondly about a clearly defined subject and chapter structure, delivered in three parts (1) The Hill, (2) The City and (3) Retreat Hell. As such it had a planned and executed focus, unlike this show, which was plainly based on the contents of a long lost suitcase. So lets not delude ourselves, into thinking this Barbican offering was about WAR or Robert Capa, its simply a cheap, off the peg merchandising opportunity of a known name.

If the Barbican truly wanted to show us war, they would have commissioned someone with the knowledge, commitment and overall sensitivity they lack, so the public could experience the best by those that described its horrors. Someone who would know it needed to include people like – Bernard, Brady, Brandt, Burrows, Capa, Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Duncan, Eisenstaedt, Engel, Fenton, Frith, Gardner, Jones-Griffiths, Jackson, Nicholls, Mc Cullin, Robertson, Rodger, Sander, Smith and Steichen. And if they wanted to do a show about Capa, almost any other published or exhibited view of Robert would have given us a more complete, accurate and complementary view of this man who successfully invented himself.

Now moving on briefly to the downstairs show The Subject of War, it was immediately better in several ways. To start with new advances in camera technology make it almost impossible to take an un-sharp image, unless it’s ones intent, as todays new advances in camera technology have given us light, easy to use, cameras with fast zoom lenses and anti shake devices to reach out and get closer to the subject, without getting closer to the action. We also have the ability to alter our ASA (ISO) up and down, and from shot to shot, to guarantee the sharpness and the depth of field needed to tailor a moment to ones intent. This show amply illustrates that so much can now be done in the camera (and or ones lap-top)

So we can produce, or more correctly have others produce for us (as with Capa and these photographers), clearer grit free moments that are more complete and compelling to the eye, emotionally, aesthetically and technically, while now also possibly eliminating what isnt wanted. And all of this technical excellence is present in abundance in this larger gallery space, which also has the added genuflections to current gallery installation thinking. In the case of this presentation this included introducing video screens, positioned (bumper to bumper) to tell two separate stories simultaneously, neither of which were digestible, and both seemingly influenced by morning soap-opera TV. One enormously large wall at the back the gallery has the appearance of a chequer-board, viewed from above, with a multitude of large images running down and across it, without giving us clue as to how to decipher its message.

However, at the opening the staircase between both these offerings seemed to offer me some momentary sanctuary from the past that valued the presence of a camera, more then the mind of the person behind it, and from the now, that seems to value the originality of the observer, more then the content of the message. Maybe Im being super-sensitive hear, but I kind of feel the designers of this poor donation to photographic understanding also felt that the base of this staircase was an ideal place to offer alcoholic refreshment, for it served as a kind of Oasis Point in this desert of deprived expression.

John Benton-Harris

This review is also published on John Benton-Harris’s own blog, The Photo Pundit

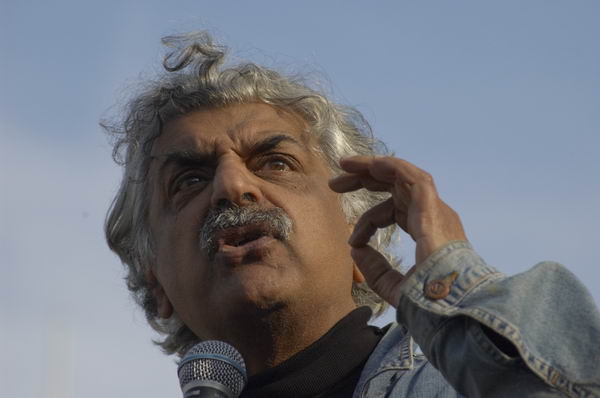

This might make a good poster in the unlikely event that Tariq Ali were ever to become our Prime Minister!

This might make a good poster in the unlikely event that Tariq Ali were ever to become our Prime Minister!