I’m still managing to post a picture every day on Hull Photos, and there are plenty more still to come, though I’ll need to scan another batch soon, but I keep forgetting to post these weekly digests here on >Re:PHOTO. Of course you can see the new pictures added each day at Hull Photos, and I also post them each morning with the short comments below on Facebook.

Comments and corrections to captions are welcome here or on Facebook.

8th September 2017

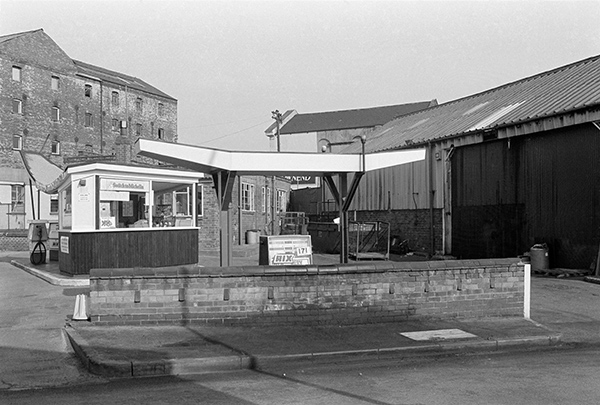

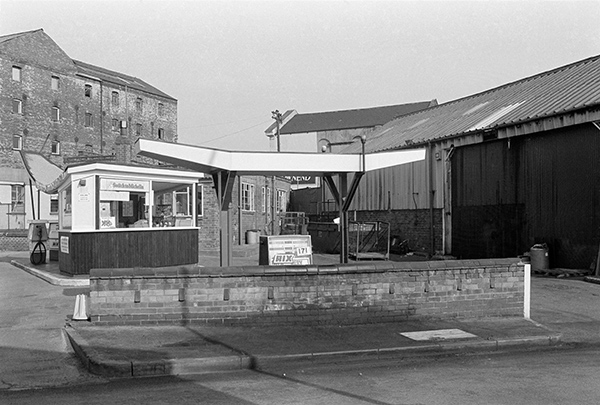

Wincolmlee and Oxford St meet at the north end of Oxford St at a fairly acute angle, and this filling station occupied the tight triangle between them, now taken up by McCoy Engineering, who occupy both the large shed and the smaller brick building in the background behind the pumps.

This was naturally a Rix petrol station, just a stone’s throw from their site further north on Wincolmlee, the petrol equivalent of a brewery tap. I loved the way it fitted into the site and the upcurved sweep of the canopy at the left, as well as the simple and symmetrical design of that in the centre.

Behind is a large factory building on Wincolmlee, still there, though for sale when I took this picture. For some years later it sold pine furniture and more recently was Mattress Master and Mould-it. The building in the background at centre right, which looks as if it might have once been a chapel has been demolished, though I think a low section of its walls, around three or four feet high, remains as a site boundary.

84-4e-23: The Oxford Filling Station, Wincolmlee/Oxford St – River Hull

9th September 2017

Underneath each of the numbers 1-6 neatly painted on this factory wall is a small wooden notice with the message ‘Reserved‘. But occupying these parking bays when I took this picture was a large heap of some unknown substance and I wondered briefly if underneath this lay buried the cars containing those privileged people who had their reserved parking spaces here. But on reflection I think the piles of whatever were only three or four feet high, insufficient to cover the revenge of some wronged worker – unless he came with a bulldozer to flatten the vehicles or it was just the managers’ bodies below them.

I no longer remember the exact location where I took this, though the frame previous was taken in Cooper St, and the next frame at the start of Cannon St, and so I think this was probably in Green Lane, in front of some long-demolished factory.

84-4e-32: Parking bays, Green Lane/Wincolmlee Area, 1984 – River Hull

10th September 2017

Somewhere in my wandering between Cannon St and Oxford St and Wincolmlee, most likely in Lincoln St, I came upon this house with painted sunflowers, the works and perhaps the work of Richard Bacon Inflatables. I think the house has now gone, and Richard Bacon Inflatables has sunk without trace, though doubtless some people in Hull – and perhaps even Richard Bacon – will remember it 33 years later.

Apart from the flower and the house door, out of keeping with the building there were other aspects which attracted me to this house, which somehow appeared like a slice cut out of a terrace, tall and thin, and marked out for further slicing by the verticals of the shadow, telephone post and drainpipe.

At the time ‘inflatables’ meant nothing to me. Did Richard Bacon make balloons, perhaps blimps, air-beds or life-size plastic doll sex toys – or even large and rather blobby plastic sunflowers?

RIBs or Rigid Inflatable Boats are still made in the area, and Humber RIBs, based further south at 99 Wincolmlee, claims to be the UK’s leading RIB manufacturer with the most extensive range and over 12,000 craft built to date and. And at 246 Wincolmlee is a large sign with letters on the wall now reading (unless more have since been lost) ‘in l t ble b at sales’, which took me a little while to decipher.

84-4e-35: Richard Bacon Inflatables, Wincolmlee Area, 1984 – River Hull

11th September 2017

This view looking south down Wincolmlee has changed remarkably little, although there have been some significant changes in the area. The bridge which frames the image has been repainted with the name of new company, Maizecor, incorporated in 1991 and still in business despite various periods of financial difficulties (during one of which in 2007 its then managing director died after falling 200ft from the top of its silo having apparently previously slit his wrists – the inquest returned an open verdict) and the rather fine streetlamps have disappeared, along with the road signs.

Gone too is the board for Bridgeside Garage, and a large metal shed for Northern Accessfloors has appeared on the corner of Scott St. But the other buildings are still present with few visible alterations, with the view down Wincolmlee to the many chimneys of the Charterhouse.

But more basic changes are hidden from view – most notably that Scott St Bridge to the left has now been closed to road traffic for around 25 years. The much-used urinal that stood close by it is also long gone, and the riverbank behind Grosvenor Mill at the centre of the picture, then still lined with wharves and buildings, is now empty with just a few bare areas used as car parks.

84-4e-51: Pauls Agriculture Limited and Wincolmlee, 1984 – River Hull

12th September 2017

Hull had a number of vandalised cemeteries – and under the Youth Opportunities Programme in the 1970s the young unemployed were put to use to further vandalise some of them, given a nominal wage for doing what they had previously done for free. This one on Sculcoates Lane had not been subjected to the official mistreatment as it was still owned by the Church of England.

There were two cemeteries on Sculcoates Lane, both overflows from another a little further east at the corner of Air St and Bankside which was the original St Mary’s Churchyard. Sculcoates in the 19th century was a densely populated area and the churchyard became crowded. The cemetery on the south side of Sculcoates Lane, where this picture was taken, was opened by the Church of England in 1818 to cope with the growing demand, and had a mortuary chapel (destroyed by wartime bombing) so became known as the Sculcoates Sacristy Cemetery.

Demand for burial space remained high – Sculcoates was a heavily industrialised area and pollution levels will have kept life expectancy in the area low – and a third parish cemetery was opened on the north side of the lane in the 1890s – Sculcoates Lane North Cemetery (also known as St Helena Gardens Cemetery.) There were relatively few burials in the Sacristy Cemetery after 1920, and these were mainly of people being added to existing graves. The last burial there appears to have been of 82 year old William Marshall (no relative) in 1955, added to the grave of his beloved wife Martha who had died 39 years earlier.

Since 2007 the cemetery has been run by and tidied up by the local community who have also photographed many of the graves for ‘FindAGrave.com’ but is still pleasantly overgrown and apparently popular with ghost-hunters, a group of whom led by local historian and Ripperologist Mike Covell heard loud moanings coming from one corner of the site and walked in on a porn film being shot there, much to the consternation of the actors in flagrante delicto. His story was widely reported in the popular press.

And no, there is no real Hull connection with Jack the Ripper, though given that thousands have been put forward as being the murderer it is hardly surprising that at least two, James Maybrick and Frederick Bailey Deeming, had a Hull connection.

84-4f-35: Sculcoates Sacristy Cemetery, Sculcoates Lane, 1984 – Beverley

13th September 2017

Another picture featuring the cobbles of Glass House Row, taken shortly after the previous landscape format image posted earlier which was on the last (39th) frame of a cassette of Agfapan 100. I stopped more or less where this picture was taken (probably moving into the shade by the wall) to reload my camera with my more usual Ilford FP4 (or Tri-X) and then took several similar portrait format images before more or less repeating the previous exposure and then waling down Glass House Row for some more pictures.

Glass House Row comes to a dead end at an industrial site and I think I had to retreat to Cleveland St to make my way up to Foster Street and the path to walk back over Wilmington Swing Bridge. A great deal of demolition was in progress in the area then and more since; the sidings for the cement works have gone and there is a different road layout with a large roundabout.

84-4f-62: Glass House Row, off Cleveland St, 1984 – River Hull

14th September 2017

Field St, off Holderness Rd, running down to Abbey St, was laid out a few years before the parish of Drypool-cum-Southcoates became a part of Hull in 1837 and was first known as Marfleet Lane. Later it became Prospect Place and in the 1960s it was renamed after a prominent Hull seed merchant, grocer and tea merchant William Field.

Field’s daughter Esther Ellen in 1873 married one of Hull’s greatest men, Thomas Ferens, a fellow Methodist Sunday School teacher though they separated during the First World War. Ferens continued to teach Sunday School throughout his life. A great philanthropist he worked his way to become general manager and then joint chairman of Reckitt & Sons, and donated much of his earnings to various causes, including the Hull Art gallery that bears his name and the University he brought into being with a donation of a quarter of a million pounds in 1925, which accounts for its motto ‘Lampada Ferens’. Ferensway was opened the year after his death in 1930. He on several occasions refused a knighthood, but was called by The Times ‘The Prince of Hull‘.

Abbey Street was only created in the 1890s, and was not named after a religious establishment but after Alderman Thomas Abbey who was a member of the local board with responsibility for laying out streets and had the reputation of being the rudest man in Hull. A B Rooms, Locksmiths and Safe Specialists, now trade in rather larger and more modern premises on Abbey Rd.

The building which this sign was on is I think that described in the Holderness Road (West) conservation area document as “Late Victorian building now altered beyond all recognition”. Formerly a commercial school, possibly a parish school, the parish relief office, parish dispensary and a “whitesmiths” (a worker in tin or other metals, including tin plate and galvanised iron) it certainly now requires a considerable leap of the imagination to recognise any of its past – and indeed from its frontage to recognise it as the building I photographed back in the 1980s.

84-4k-01: A B Rooms Locksmiths, Field St, 1984 – East Hull

You can see the new pictures added each day at Hull Photos, and I post them with the short comments above on Facebook.

Comments and corrections to captions are welcome here or on Facebook.

(more…)