Around 100,000 Tamils marched through Westminster today to persuade our government to take action over the Sri Lankan genocide of the Tamil population, to shame our media into breaking their silence over what is happening there and to call for the establishment of a Tamil homeland, Tamil Eelam.

Marchers at the Houses of Parliament – with Big Ben

For a second time this month, I felt ashamed of the BBC. Ashamed because I grew up believing that our national broadcasting organisation was the best in the world (and in some ways it still is.)

Of course its first glaring failure this month was the kowtowing of its management to Israel when they decided not to broadcast the Gaza appeal. A second blot on the organisation came today. This evening, fresh home from this massive demonstration in London by Tamils, I turned on Radio 4 for the six o’clock News and found to my amazement that it hadn’t happened. There was not the slightest mention of it. Later I checked the BBC News web page – again nothing.

Probably the largest popular demonstration in the country since the massive anti Iraq war demo in 2003 is news. Between a third and a half of the UK’s Tamil population on the streets in Westminster is news. And certainly the genocide that is taking place in Sri Lanka, with government troops shelling areas packed with civilian refugees is news. But apparently not for the BBC.

Sri Lanka – Background

Sri Lanka is another of Britain’s colonial cockups. When Britain took over Ceylon in 1796 there were separate kingdoms, each with several thousand years of history and which had been treated separately by the Portuguese and Dutch colonists. But in 1833 the British decided to unite the Tamil and Sinhalese areas to make their administration more convenient. And when we got out of India and gave Ceylon its independence in 1948, little if any thought seemed to have been given to the division. The constitution – on a Westminster model – handed the Sinhalese a built-in majority and had no safeguards for the minority Tamils, around 30% of the population.

Most Tamils in Sri Lanka are Hindu, while nearly all the Sinhalese are Buddhist. A considerable minority – over 15% of Tamils are Christian and there are also some Tamil-speaking Muslims, who regard themselves as a separate group from the other Tamils

Within months, the government had deprived more than a million Tamils of their citizenship. These were the descendants of Tamils the British brought from India in 1834 to work their colony – and who joined Ceylon’s Tamils who had lived there for at least 2500 years. Many Tamils were also driven from their homes and replaced by Sinhalese in a deliberate policy to reduce the Tamil domination of key Tamil areas.

The government voted to make Sinhala the official language, with Tamil and English having only a secondary status in 1956, and many Tamils in government employ lost their jobs. A peaceful protest inspired by the example of Ghandi was met by riots encouraged by the government, with police, army and government taking no action to stop the killings.

The last official links with the UK were broken in 1972 when the government declared Ceylon to be a Buddhist republic, Sri Lanka, although it remained a member of the Commonwealth. The setting up of the republic further marginalised the Hindu, Christian and Muslim Tamils.

In 1983 the government took part in a massive pogrom against Tamils which was widely reported in the international media. It was the start of a series of major actions against Tamils that continue to this day, including bombings, tortures, rape, the assasinations of human rights activists, politicians and aid workers.

The response of the Tamil people was to try and establish a Tamil state, Tamil Eelam, and a key organisation in this has been the Tamil Tigers (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam or LTTE.) The LTTE carried out a number of attacks and was for some years in effective control of Tamil areas in the north of the island, setting up banks, courts, social services and other aspects of civil administration in some areas. This infrastructure has been a major target for the Sri Lankan Army and Air Force with much being destroyed or captured.

The LTTE made headlines across the world with some of its attacks, including a suicide bomb at the country’s major Buddhist temple in 1998 in which 16 people were killed and a raid on the international airport in Colombo which destroyed several aircraft in 2001. But government restrictions on newspapers and journalists mean that they have effective control of the news and most of what happens in the Tamil areas is not reported.

There have been various attempts at peace settlements, particularly since 2000 when Norway became involved as an intermediary. Both sides accuse the other of breaking every agreement made, in particular over agreements to work towards a federal state.

The Sri Lankan Army appears to feel that at last it has the Tamil Tigers on the run and is determined to try and finish them off, whatever the cost in civilian deaths and injuries, bombing and shelling areas where they think the Tigers are hiding and where they know hundreds of thousands of civilians have taken refuge. Civilians that manage to escape these areas have been put into camps where the world’s press and humanitarian organisations are refused access – and about which we can only presume the worst.

Saturday’s march

Demonstrators dressed in yellow and red get ready to march

But I am only reporting from Westminster, and the massive demonstration there, united in its strength of feeling and dedicated and intense in its demand for an independent Tamil homeland, Tamil Eelam, in the Tamil area of Sri Lanka. Although the chanting was loud and feelings were rightly running high against the atrocities, with street theatre acting out the attacks of the Sri Lankan army on the people and children and adults dressed in bandages and blood (or rather red dye) stained clothing, there seemed little danger of public disorder.

When I arrived around 12.40, the streets from Vauxhall station to the assembly point by the Tate Gallery were already crowded with people and I had a job to push my way through to the front of the march – although fortunately everyone was very polite and helpful (including the stewards and police – this was a march it was a delight to photograph.) It was a march that never really started, but from a little before 2pm slowly edged its way forward in small steps, and by a little after 3pm the front of the march was in Parliament Square.

Marchers outside the Houses of Parliament

Although there are over 50 million Tamils in India and only 3.1 million in Sri Lanka, most of the the UK’s 200,000 or so (estimates range from 150-300,000) come from Sri Lanka as a result of the discrimination and persecution their community has suffered there at least since the 1960s. Most of them live in London, particularly in East Ham, Walthamstow, Brent, Merton and Croydon. Among the Tamils in the UK are around 2,500 NHS doctors.

Many of the police along the route were in fireproof clothing, and stood clutching fire extinguishers with the pins removed for immediate action. They were not fearing a burning of flags or some incendiary attack on Parliament, but were ready in case some individual attempted to burn themselves to death as a protest. Fortunately they did not need to rush into action.

It was a very slow march up past Parliament, with people stopping at intervals to sit down on the road, to the considerable annoyance of the police, who at times made some pretty ineffectual attempts to speed the march up. But there were so many demonstrators they were powerless; even though the demonstrators generally law-abiding they were determined to have their day and take their time.

Sri Lankan MP, M K Shivaji Lingam (inn brown coat)

Among those marching was at least one Sri Lankan MP, M K Shivaji Lingam of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), who has stated that “it will be impossible to crush or destroy the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) militarily” and that “Hindu culture (in Sri Lanka) is at stake” threatened by the attacks by government forces that have taken over and damaged many Hindu shrines. In December he visited India and obtained the support of several Hindu groups for the Tamil cause.

I left around an hour later, with marchers still streaming past the Houses of Parliament, with the end of the march still coming up Millbank, and Horseferry Road just reopening to traffic. Bringing up the rear was the decorated bus or ‘tiara’ built in Karachi for Dalawar Chaudhry who owns a restaurant in Southall, which as well as its normal extensive decoration had posters calling for an end to the ethnic cleansing and highlighting the killing of politicians and human rights activists in Sri Lanka.

More pictures from the event on My London Diary shortly

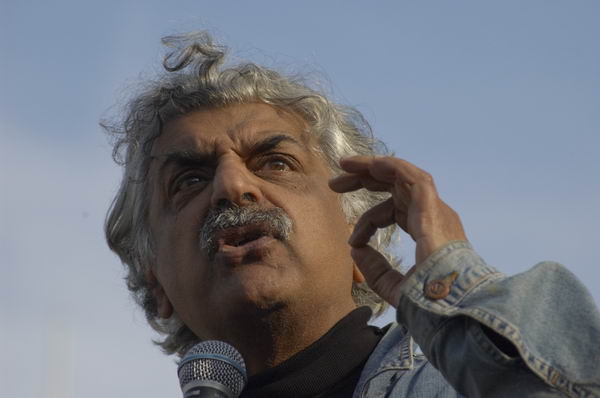

This might make a good poster in the unlikely event that Tariq Ali were ever to become our Prime Minister!

This might make a good poster in the unlikely event that Tariq Ali were ever to become our Prime Minister!