Last December around 2-300 people marched from Belgrave Square in London to Harrods passing many designer shops that sell fur-trimmed garments on the way and voicing their opposition to this cruel, inhumane trade which involves the deliberate and callous ill-treatment of animals. Some of the same people were there for another march on Saturday, but in general it seemed a more middle class and polite affair, with rather more people present, nearer to 500.

Anti-fur marchers outside Prada, Sept 2008

Looking at this crowd, the organiser’s plea for them to be sensible and not to try anything silly with half the Metropolitan Police watching them (and one of the many vehicles I noticed was from the City of London force) seemed superfluous, while in December there had appeared to be rather more chance of something happening.

Policing did seem to be excessive, with officers all along both sides of the procession and more in front of virtually every clothes shop the march passed – certainly all those that sell fur. I got pushed in the back by police on several occasions as I stood on the curb to photograph the marchers and was pulled back rather firmly as I walked onto the pavement. Showing my press card I was told “It makes no difference.” I argued but got nowhere, so simply walked a few yards further up the road (actually towards a fur shop) where the police seemed to have no problem about me going off the road.

For once the FIT team seemed busy photographing demonstrators and I didn’t once notice them photographing me or the other photographers present. Of course I could just have missed it, but usually they like to make sure people notice they are being watched.

In December, outside Harrods, I’d shot from inside the march:

Anti-fur March outside Harrods, Dec 2007

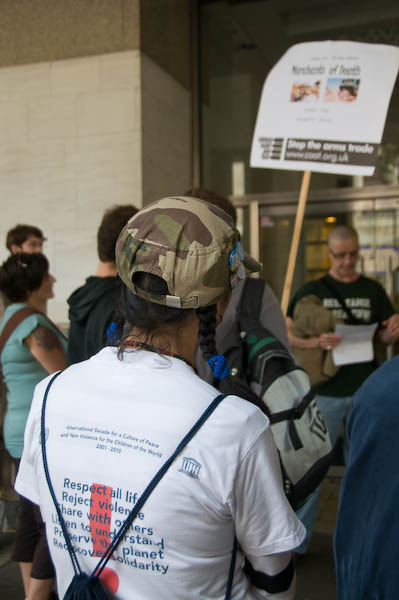

So this time I’d decided to try from the other side of the fence there:

Anti-fur March outside Harrods, Sept 2008

Harrods is a particular target as the only department store in the country to still be selling furs. As the placard points out we have a peculiar situation here that while fur-farming was banned here, the law failed to ban the import of fur farmed in other countries – under much more cruel conditions than those were allowed before the ban here.