Rhubarb Rhubarb (this year’s event was 26-29 July) is a festival with various aspects, including the seminar “East Meets Eastside” on the Thursday afternoon which I was unable to attend, although the reports of it were intriguing. Another is the exhibitions held at the main centre of the event, which this year for the first time was Curzon Street Station close to the centre of Birmingham, as well as at associated venues. The New Art Gallery at Walsall was one of these with a show of colour work by Ian Wiblin, “Recovered Territory“, which continues there until Sept 9, 2007.

The New Art Gallery, Walsall

The art gallery is a fine modern building in the centre of Walsall, standing out among some indifferent modern sheds and remaining proud Victorian relics as a symbol of the possibilities for regeneration of the area. I arrived in Birmingham on Thursday afternoon just in time to jump on a coachfor the short trip to Walsall, along with a few of the other reviewers, volunteers, organisers and others at the festival. We were then treated to the full Birmingham experience of a traffic jam on the motorway, along with a short circular tour around Walsall’s town centre when our coach driver missed the gallery first time round.

Inside the gallery a warm welcome awaited us, along with some even more welcome refreshments, before we took the lift the the top floor, where Ian Wiblin’s work was on show. This is a fine exhibition space, with large windows giving a view over the surrounding town (unfortunately a little rain meant we were unable to use the roof terrace), and a 30 foot or so high ceiling which perhaps rather dwarfed the small colour images on show, well spaced out on the tall white walls.

Ian Wiblin and visitors in the gallery reception area

The old Polish city of Wroclaw had a largely Germanic population from the 13th century, and in 1741 officially took on the German name of Breslau, later becoming one of the major cities of Prussia. By the start of the Second World War, the Nazis had cleared out remaining Poles along with most of the Jews, and the city became a Nazi stronghold, the last German city to fall to the allies after a long siege by the Red Army. Almost three quarters of the city was destroyed, and many of the German civilians were killed. The rest were evicted in a post-war settlement, Stalin sliding Poland toward the west, incorporating Breslay under its Polish name of Wroclaw. The city gained a new Polish population displaced from Lwow, (renamed Lviv and added to the Ukraine), along with rather more Poles from Warsaw and Poznan.

In Wroclaw, as in the rest of the “recovered territories” large investments were made to remove traces of its German past, including the removal of many German signs and inscriptions and the restoration of many of the ancient building in order to promote a partly or largely mythical Polish past.

Wiblin first visited Wroclaw shortly before the fall of communism in 1989, producing the series of images “Wroclaw” shown at the Photographers Gallery, London (and elsewhere) in 1990. He returned to the city for a few days in 2006, working in colour to produce “Recovered Territory.” The title refers both to the lands incorporated into Poland following the war and also to his personal impression of the change from a state-controlled communist city into a capitalist one. As with his earlier black and white work, these carefully framed fragments showed an intense and often unusual, sometimes surprising vision, glimpses that reflect past history that are often compelling, sometimes strangely uneasy. Perhaps I found the need for some text on the walls – perhaps equally fragmentary – to anchor these visions to their context.

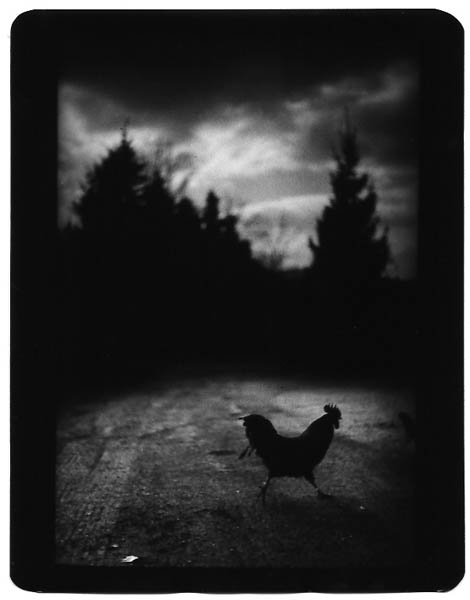

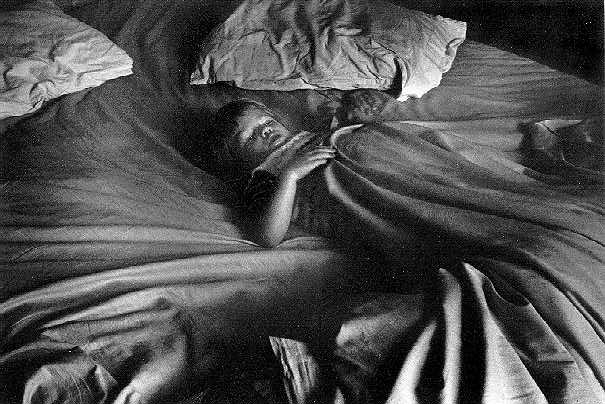

In Wiblin’s previous black and white work from Wroclaw as well as in the images in “Night Watch“, the book from his year in residence in Cambridge in 1994-5, Ian’s printing added greatly to the impression that the images created, its dark charcoal greys and glowing lights being very much integral to the syntax with which he worked. Here the images were in colour and in a much more neutral key; perhaps an area which he might exploit more fully. But it was a show I found intriguing and powerfully evocative, and I look forward to more work by him in colour.

It was perhaps a shame that there were not more of us on the visit – and that there were not more shows around the area as a part of the festival. And although it was good to see those that were taking place at Curzon Street Station, they could perhaps have been made a more positive feature in the programme. Since much of the work was in the review areas, viewing was really only possible in the breaks during the day. Some of the photographers who only attended for a single day will probably not have seen much of this work.

Curzon Street Station, seen from the train.

Curzon Street Station is a fine building, the first station linking Birmingham to London, built in 1838, and built to impress. Although the tracks are long gone, the building still impresses, dominating the largely cleared area around it and providing light, airy spaces within, although in some aspects in need of refurbishment. With some investment it would make a fine centre for photography and digital imaging.

I was fortunate to be reviewing in a room containing perhaps the best of these shows, ‘Otherlands‘ with some exceptional work by a number of photoographers including Vee Speers, and Reiner Reidler (of whom more in later features), and there were aslo some pleasing works in the more public areas such as the stairways and landing, notably a set of John McQueen‘s colour pictures showing the once proposed Birmingham Ship Canal with a toy liner cruising the city. There were also a few images I related less positively to, including a pair so badly off-colour that it made me feel ill to view them, but fortunately such things were rare.

More of my impressions from Rhubarb shortly.

Peter Gwyn Marshall