You have just missed one of the world’s best photo festivals (although the exhibitions remain open until Sunday.) I’m not actually sure I should tell you about it, because it was already standing room only for at least one session, and part of what makes it so great is it’s manageable size. If you all come for the next one it may not be the same!

I first heard of Bielsko-Biala when I was invited to show work at the first FotoArtFestival there in 2005. I hate to travel. I’ve even refused jobs on the grounds that I couldn’t get there on a Zone 1-6 London Travelcard. Before then I hadn’t been on an airliner since I was about 15 – and then only on a tour of the workshops at London Heathrow where my eldest brother then worked (and I suspect it was a DC-3.) I started taking my ‘carbon footprint’ (not that we called it that then) and energy use seriously in the late 1960’s, when I was “a friend of the earth before the earth had friends” or at least before the organisation was set up here in the UK.

Two names made me decide to bend my principles sufficiently to make the trip to Poland as well as sending work there. I wanted to meet Eikoh Hosoe and Ami Vitale.

Gunars Binde, Eikoh Hosoe, Ami Vitale and Peter Marshall. Photo by Jutka Kovacs

I also wrote about many of the other fine photographers I met there, including Stefan Bremer Gunars Binde, Sarah Saudek, Pilar Alabajar, Shadi Ghadirian, Lars Tunbjork, Bevis Fusha, Ali Borovali, Obie Oberholzer and Vasil Stanko for ‘About Photography‘, and although those features are no longer on line there, you can find them on the ‘Wayback Machine‘ along with those about photographers unable to come to Bielsko, such as Joachim Ladefoged and Boris Mikhailov, and Mario Giacomelli, who of course died in 2000. One curious feature of many of the pages on the Wayback machine is that my photograph is replaced by that of the current guide.

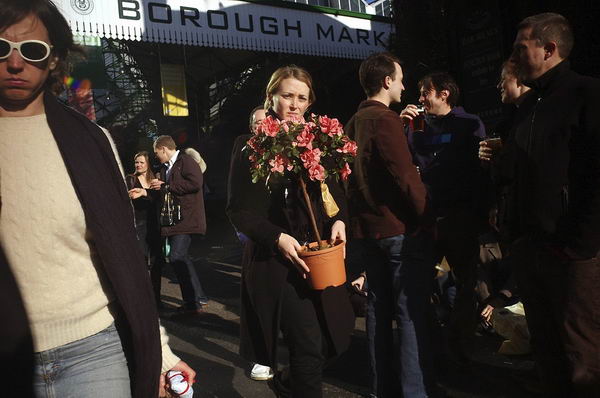

This year’s FotoArtFestival also brought a range of stars to Bielsko-Biala, including Sarah Moon, Misha Gordin and the author of one of the best-known histories of photography, Naomi Rosenblum. The outstanding show for me was Walter Rosenblum‘s ‘Message from the Heart‘ and I had the privilege of visiting it together with Naomi and his daughter, the film-maker Nina Rosenblum. A screening of her film about her father was another highlight, despite some technical problems. I was there to give a presentation, which included some of my own work as well as images by John Benton-Harris and others who have photographed on the streets of England.

At the moment I’m still exhausted from my trip there and the journey home, and still writing up my memories and processing the images I took there on my highly pocketable Fuji Finepix F31fd. Even though these are only jpegs, it is still worthwhile importing them into Lightroom and adjusting as if they were raw files. The difference can be astonishing, and it somehow seems to result in less degradation than similar processing in Photoshop or other image-processing software.

The F31fd may not be as good as the Nikon D200, but it is considerably easier to carry! And if a pink phone was good enough for Eikoh, then I think I can manage with it for things like this.

Eikoh Hosoe photographing in Alcatraz, Bielsko, Poland

Much more later!

Peter Marshall