Back in 1910, a Chicago factory inspector Helen Todd, speaking at an event launching a new campaign for votes for women picked up on a comment made to her by a young woman worker that votes for women would mean “everybody would have bread and flowers too”, elaborating it in her speech, quoted in part in Wikipedia:

“… life’s Bread, which is home, shelter and security, and the Roses of life, music, education, nature and books, shall be the heritage of every child that is born in the country …”

Later that year, Todd was involved in the Chicago garment workers’ strike led by The Women’s Trade Union League, making a number of speeches, and “We want bread – and roses, too” was one of the slogans used by the strikers. It was soon picked up by others, including James Oppenheim who published a poem, ‘Bread and ROses’ in 2011, and by a number of leading suffragettes and women trade unionists including the Polish-born American socialist and feminist Rose Schneiderman of the Women’s Trade Union League of New York, with whom the phrase became associated.

It was the 1912 Lawrence textile strike, often known as the Bread and Roses strike, that made the phrase well-known. Most of the unskilled work in the mills was carried out by immigrant women, and at the start of the year they found without warning that their wages had been cut because of a new Massachusetts labour law which cut the working week for women and children fromf 56 to 54 hours.

The established unions were not concerned with the loss of pay as they mainly represented the skilled white male workers who were unaffected. The IWW came in to organise the immigrant workers, who had come to the USA mainly from countries in southern and eastern Europe and the Middle East – and spoke around a couple of dozen different languages. They set up relief commitees and organised large and noisy protests where some women carried a banner “We want bread and roses too.”

The employers and the authorities hit back with force and dirty tricks, including arresting the union leaders on clearly false murder charges and getting the firemen to turn their hoses on the marchers in freezing weather, but newspaper coverage of this made the strike a national outrage, eventually forcing the employers to agree to almost all of the strikers demands, including a a 15% pay raise, double pay for overtime, and an amnesty for strikers.

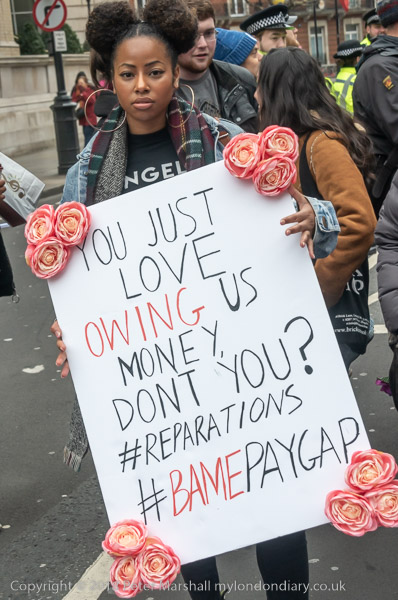

‘Bread & Roses’ was the inspiration for the Women’s March in London (and similar events elsewhere around the world) on January against economic oppression, violence against women, gender pay gap, racism, fascism, institutional sexual harassment and hostile environment in the UK, and called for a government dedicated to equality and working for all of us rather than the few. Many of those organising the event and taking part, like those who struck in 1912, were from our migrant communities, and there are certainly similarities between the IWW’s tactics in the 1912 strike and the activities of some of the smaller independent unions that are now active with low-paid workers.

Speakers with scripts in orange folders and directed by a BBC camera crew

The march began outside of the BBC, with a few speeches on the steps of the BBC church, All Souls in Langham Place, in a rather curious short rally that appeared to be both scripted and stage-managed by a small camera team from the BBC, who were directing the women who spoke, and generally barging their way through some of the protesters and photographers. I was told they were making a documentary about a group of the women, but if so they clearly have a very different idea of documentary to me, and it seemed more like a play. Other than that of course the BBC as usual ignored both this march and any other protests taking place in London on the day.

More at Women’s Bread & Roses protest

______________________________________________________

There are no adverts on this site and it receives no sponsorship, and I like to keep it that way. But it does take a considerable amount of my time and thought, and if you enjoy reading it, a small donation – perhaps the cost of a beer – would be appreciated.

My London Diary : London Photos : Hull : River Lea/Lee Valley : London’s Industrial Heritage

All photographs on this and my other sites, unless otherwise stated, are taken by and copyright of Peter Marshall, and are available for reproduction or can be bought as prints.

To order prints or reproduce images

________________________________________________________