The Maison Europeenne de la Photographie (MEP) is perhaps my favourite space to go to look at photography, and I only wish we had something like it in London, though of course a part of its charm is that it is just a few yards from the busy pavements of the Rue St Antoine where you can eat and buy real French food along with the ordinary Parisians. I’ve spent many happy hours and days wandering the Marais, and if it has lost a little of its charm over the years under the relentless spread of boutiques it remains one of the great urban experiences.

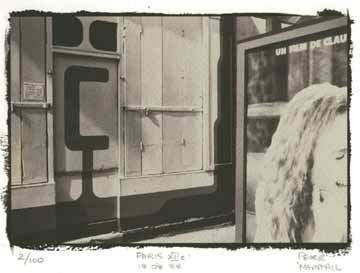

The Marais in 1973, from Paris, 1973 (C) Peter Marshall

Larry Clark‘s “Tulsa, 1963-1971” is one of three major shows currently there (until 6 Jan, 2008) and is an extensive showing of his work, most of which appeared in the books ‘Tulsa‘ and ‘Teenage Lust‘.

An important part of the show was an edited version of a film in which Clark talks about his life and work. This was in English, but with French subtitles. These provided an interesting comment on the differences between English and French ways of thinking, as in many places they diverged. While Clark’s responses were American laconic, the translation was French philosophical.

Clark’s story is probably too well known to need a detailed exposition, and as I managed to lose my notes (it was a very good party on Thursday night) there may be a few misplaced details in this outline, but I don’t think it really matters.

Clark was born in 1943 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which, from memory, Oscar Gaylord Herron – also from Tulsa – described in his ‘Vagabond‘ (1975) as the jewel in the bellybutton of America, bang in the middle and as number 10 on the list of Soviet missile targets. His father was a door-to-door book salesman, but when business got really bad, left the job and worked with the family business that Clark’s mother had established. This was in baby photography, going to homes and photographing newly-born infants.

When Clark was 14, his father came home one day, took a look at him sitting around downstairs and told him he looked like a piece of shit before going upstairs and hardly ever coming down again or talking to Clark. Family life took on a very curious quality, with his father staying upstairs, eating food which his wife took up to him, although Clark also writes that his father gave him three dollars every Friday to go out.

At his school in one of the poorest areas of the city, Clark mixed and befriended many other kids who also had trouble at home. Kids who arrived at school beaten and bruised; girls who were screwed by their brothers and probably their fathers and more. Hanging out with these kids he learnt how to extract amphetamines from inhalers – his three dollars bought three of them – and get high.

Also at 14, he began to help his mother taking baby pictures, and in a year or two he was a photographer, taking these on his own. Clark realised that he needed to get away from his family, and at 18 left home to go to study photography at Layton School of Art in Milwaukee (Wisconsin). It was there he saw the work of W Eugene (Gene) Smith in Life magazine, and realised that there was rather more to photography than taking baby pictures.

When he returned home, he began to take photographs of his friends and their wayward lifestyle, very much as one of them. Then the army claimed him for a couple of years and after that he moved to New York, trying unsuccessfully to make a living as a photographer. There he met and photographed Gene Smith and also the friends he made – again on the fringes of society.

He left New York and went back to Tulsa with the idea of making a film, telling the truth about the things that were happening in America, with the kind of people that he knew. He bought a camera and sound equipment, but then found it impossible to work on his own. Looking at his photographs he decided instead that they could be a book, although there were gaps in his record that he need to fill, and he went back to photographing his friends to do this.

There is a very strong sense is which the books are like films, showing a story in a very similar way. Clark felt that photographers before him had stopped short, there were things about America that they were not prepared to show. Drugs weren’t supposed to exist in America, nor for that matter was sex (and certainly not incest) and he was determined to show the truth about the kind of life he had been a part of.

Although he exaggerates – there were photographers who had photographed virtually all aspects of the American underbelly as well as those who concentrated on Mom and apple pie – he did so in a much more personal and considerably more intense manner, pulling few if any punches. When Ralph Gibson‘s Lustrum Press brought out Tulsa in 1971, it certainly created a stir.

But in reality, little it showed was news. It may not have featured widely in pictures, but Kerouac’s ‘On The Road‘ was published in 1957 (I picked up my paperback copy on a second-hand bookstall in Hounslow in 1963) and there were plenty of other books. Kerouac’s cast of friends were of course rather more literary, but there was still plenty of sex, drugs and aimlessness, if rather less anger than in Clark’s work.

Clark was able to work the way that he did because he was living – certainly at times – the life that his friends he photographed were living. As he says in Tulsa, “once the needle goes in it never comes out.” He worked with a Leica to avoid the clunk of the mirror with an SLR, the quieter, lower tone of the slow cloth shutter getting in time, as he says, almost musical.

As well as anger, there is also a lyricism about some of his work. In one of my favourite images, a woman sits back in a chair, seen from the side, injecting herself in the right arm. Above the waist she wears only a white bra, and she is lit strongly from the window at top left of the image. The bright light on the white fabric, and also to a lesser extent on her skin are diffused, perhaps by a little greasy fingermark on the lens or filter, creating an incredible glow.

Clark’s work influenced many young photographers, but was also important as a source of inspiration for films such as Taxi Driver and Drugstore Cowboy, and both Martin Scorsese and Gus Van Sant are great fans. When Clark saw Drugstore Cowboy he thought that this guy was treading on his turf, and when they met at an opening, he told Van Sant that he wanted to make a film. This led to ‘Kids‘ (1995) and other films followed.

Large Image Collections on line

MOCA search gives 182 results

Addison Gallery search finds 134 images from Teenage Lust and Tulsa

LACMA search shows 132 images

Other sites

Larry Clark on Myspace

Official Website – under construction in Nov 2007 – but try later.

Luhring Augustine

Artnet

Pavement

Salon

Larry Clark